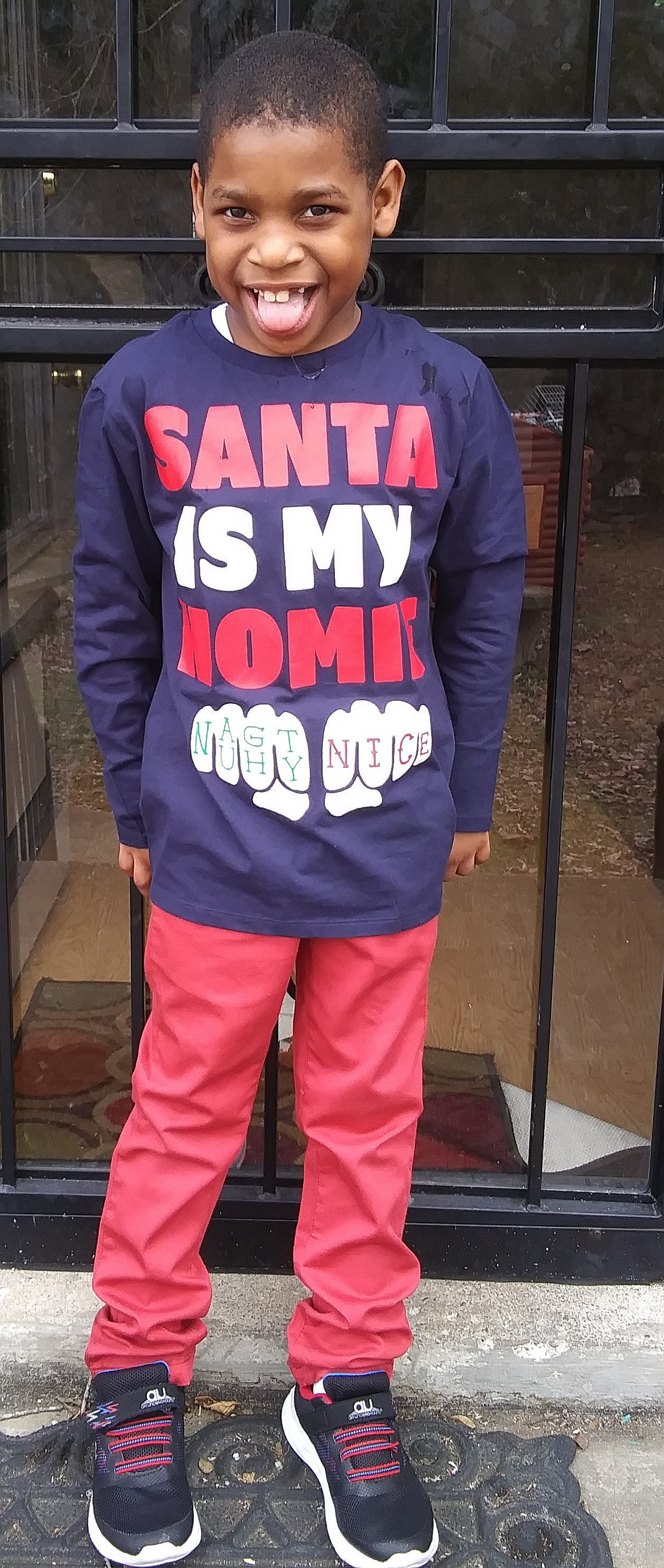

It wasn’t long after our son Theodore was born that my husband, Daniel, and I noticed how incredibly happy he was. As in “Clap along if you feel like a room without a roof” kind of happy. He barely cried, or made much noise at all, and his general disposition was one of extreme glee day in and day out. We rarely saw any sort of sour expression on his little face, even when he was hungry, feeling unwell or needing a diaper change.

My husband and I thought for sure we’d won the lottery by having the world’s happiest baby. Theo’s high-watt smile was so arresting that it would stop strangers in their tracks. We were thrilled that our child had a magical quality to him, especially one that brought people together in a positive way. Little did we know that his extreme exuberance was an indicator of something much more serious.

Shortly after his first birthday, we received the diagnosis that would change our lives forever: Theodore tested positive for a rare neurogenetic disorder called Angelman syndrome. AS is a random, equal-opportunity syndrome that affects approximately 1 in 15,000 people, and presents itself primarily as extreme neurologic impairment. AS affects both sexes and all races equally.

While the brains of children with AS are completely normal and anatomically correct, a genetic microdeletion on the 15th chromosome causes massive global delays, including debilitating seizures, mobile and motor affliction, loss of functional speech, dyspraxia — a developmental motor coordination disorder — and apraxia, or the inability to perform purposive actions.

AS is often misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy or autism. Interestingly, Angelman kids are generally very social, and often seem possessed of a happy disposition. They exude love, and, in Theo’s case, dole out hugs and kisses regularly. As many who have met him know, my son is loves making friends and sharing his affection.

I do think that the silver lining is his ability to be happy despite the immense challenges he faces. Theo has suffered his share of seizures, is not capable of basic functional speech and just started walking at 3.5 years old. He’s on a special diet to control seizures, and takes medication daily. He barely slept for the first three years of his life and only now is beginning to sleep somewhat normally.

We have spent the last few years establishing a silent language between ourselves and Theo by translating his expressions and gestures, and building on these tiny but crucial moments to understand how his brain is working and what he’s trying to convey to us. Like many families who are desperate to connect with their non-verbal children, we’re also dedicated to using Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) apps, where Theo can “talk” to us by tapping symbols on his iPad.

While I think we’re doing a decent job finding our way, I can’t sugarcoat reality. Our lives are not easy and have radically changed since the moment we received our diagnosis. Acceptance, for me, has become a daily ritual. Personally, I find that it helps to think less about the future, and to focus more on my son right here and right now. He is smiling as I write this, and that makes things OK.

The Early Signs

At 7 months, Theo still wasn’t sitting up or rolling over. His body seemed to be made of jelly. His core was incredibly weak, and he had little command over his body movements. Frequently, his limbs flailed, and we noticed an uptick in jerky movements. What’s more, at a time when other kids his age were kneeling, teetering and attempting to pull themselves up, our son showed no desire to to walk, only to lay flat and laugh at everything around him.

As he grew, his inability to grasp, move, crawl, turn or walk was beginning to weigh on us heavily. His first pediatrician called us “alarmist” for our worry, and for the request we made for genetic testing.

Sure, this was our first kid and we were no experts, but being somewhat shamed for our concerns felt wrong. We never returned to that doctor’s office, and found a pediatrician who listened and took action. In fact, the very first time she met Theodore, the second pediatrician did two things within the first five minutes: She told us we were right to be worried, and that something was terribly amiss with his development, and then she ordered genetic testing on the spot. Eight weeks later, we had the diagnosis of Angelman syndrome.

The Diagnosis: A New Reality

When I learned I was pregnant, I did what every first timer does. I bought books, I created a birth plan and I consulted with all of my friends about pregnancy and giving birth. I was thoroughly organized and I had it in the bag. At one point in the pregnancy, when we were informed that our fetus could potentially have Down syndrome, my husband and I invested in a hardcover copy of Andrew Solomon’s “Far from the Tree,” a well researched and respected book that succeeds by highlighting the differences between parents and atypical children. My husband and I meditated on the potential reality we were facing and felt ready for anything. Months later, our son was born happy, healthy and there were no red flags present indicating Down syndrome or any other disorder.

Of course, on the day the diagnosis of Angelman syndrome came our way, over a year later, we felt prepared for absolutely nothing at all. Not only did we find ourselves scrutinizing our decisions, but we also felt suddenly adrift. We thought: What is Theo facing here? How are we going to get through this? Where in the world are we supposed to start?

In those early days after the diagnosis someone sent me a link to Emily Perl Kingsley’s moving manifesto “Welcome to Holland,” written for parents facing a special needs diagnosis for their child. It’s recommended reading, and I appreciate the idea behind it. But I don’t agree entirely with what she says.

It’s not that Kinglsey is wrong. I just felt differently. Kingsley wrote about finding herself in a different place than intended, and adapting to a different path and finding new guidebooks for the new direction. I felt like we had none of that. No guidebooks and not even a general idea of which direction to head in.

I equate our experience to being dropped in the middle of a bustling city with buildings so tall they block the sky. We were without a map and devoid of orientation. Because the buildings blocked out the skyline, we had no sense of what direction was best, and what to use as a guide. There is no road map for parenting a special needs child, especially at the start. You must blaze your own trail.

Finding Your Tribe

Thankfully we live in an age where the internet can instantly connect us to others on similar paths, seeking answers for their children. Facebook was a great resource for connecting us to families facing this syndrome. Every day, we log on and share our worries, questions, answers and advice. This community has helped us immensely, and though I haven’t met many of these other angel families face to face, I owe them for guiding us through some of our most difficult times.

Navigating Early Intervention

Got a diagnosis? OK, that at least sets you in a vague direction of where to seek more information and find resources. Thankfully, there are early intervention and Medicaid benefit programs in every state (to see where your state ranks, go here), but they all vary in terms of the services and support they offer. It’s tricky to navigate, especially if you don’t have a confirmed diagnosis.

Start early. If you can emotionally muster it, start the day after a diagnosis. Or start the day you and your pediatrician suspect something is amiss. The sooner your child is in the system and evaluated by specialists, the sooner they can receive therapies and related services to help them improve and thrive. I still run into many families who are unaware there are state services available (at little to no cost) for children with special needs.

Unfortunately, large quantities of forests will be destroyed to to create all the paperwork you will have to fill out for these evaluations and therapies, but this tedious chore is minor compared to what your child can potentially gain in return. Your life will change, and because “the process” requires constant attention, you will spend copious amounts of time on the phone with insurance companies, or booking medical appointments, or considering therapies or interviewing caretakers who specialize in caring for special needs children. It’s a hard reality that special needs parents must dedicate so much of their lives to the process, but it’s worth it.

Documentation is Key

One important point: Keep copies or printouts of every important evaluation or medical test, especially any that reveal genetic or diagnostic results. Keep them stored in a safe and waterproof place. I recommend creating backup copies of all of them. I scan all print-outs of important medical information using a free scanning app, like CamScanner. It helps to be able to access information quickly, like when insurance or one of Theo’s doctors calls with a question. The more documentation you have, the easier it will be to complete all the educational, insurance, and medical forms in the future.

Prepare for a Fight

It’s probably the last thing parents of newly diagnosed special needs children want to hear, but fighting for your child can and will be a full time job — especially in the beginning.

Being the parent of a special needs child doesn’t give you special treatment. The system may guide you and even hold your hand, but it won’t do the work or fight your battles for you. That responsibility falls solely on the shoulders of parents.

At the start, you’ll be faced with decisions and more decisions. Ask questions, listen attentively and take plenty of notes. In this world, information is power, and when your special needs child (who may be non-verbal and non-mobile) needs to fight to improve his quality of life, you’re going to need all the ammunition you can get.

You will battle with doctors who disagree with your intuition or wishes. You will fight with insurance representatives who will deny adaptive equipment for your child. You will struggle to get the right therapists and educators and services to help your child. You will butt heads with the school system when creating an IEP (Individualized Education Program), which is the time you’ll set goals for the school year.

Being a warrior parent will become part of who you are. You can do it.

Processing Grief and Finding Acceptance

I choose to honor and recognize my grief personally. For parents facing a diagnosis, I will simply say that yes, like any difficult life transition, there will be stages of emotion, and everyone moves through them at a different pace and in different ways. I don’t want to gloss over this, but depending on your diagnosis and the severity of what your child is experiencing, adapting to parenting a special needs child will vary. Everything is subjective and everyone’s situation is different.

Some wonderful books that are helping me through this process include “When Things Fall Apart“ by Pema Chodron and “To You; Love, God” by Will Bowen. I also appreciate the writings of Jamie Varon, who seems to perfectly capture the hardships of life.

A Typical Child Inside

Some moments, I think Theo is as typical as they come. He’s incredibly playful, sometimes sly, and loves a good joke. He is quick to laugh, bust out dancing, and likes to grab his drink and settle into the couch when one of his favorite shows is on. While it’s so easy to think about everything he can’t do and may never be able to do, I relish these beautiful moments when he reveals his true self and shows us the typical kid that exists inside.

I constantly remind myself of this, especially when I’m hesitant to introduce him to a new concept or idea — like letting him take a ride on a kiddie roller coaster or taking him to a movie for the first time. The hesitancy I feel is often a reflection of my own fears and insecurities.

When I set aside the idea that he’s a child with special needs, and focus simply on him as a child, I allow in wonderful opportunities and experiences. My advice to parents: Be present. Be a parent. Treat them special but not perpetually as special needs. They are still kids, after all.

The Unconditional Love of an Angel

When we received Theodore’s diagnosis, a very good doctor with a very poor bedside manner informed us that our son would never walk, never talk, never love and would never know we were his parents. She seemed determined to paint a bleak future of having a son who would always exhibit the mental capacity of a child and would require life-long care.

Her words hurt, but we knew — even in that darkest moment — that she was wrong. We called her out for being emotionally irresponsible and stood our ground, insisting that our child was loving, present and capable. Now, years later, we know for sure that her words were just words, and not the truth.

The size or value of your love doesn’t change, even when it’s revealed that your child is different from what you expected.

We have never loved him differently, and certainly not any less, even with this terrible condition hanging over our heads. But what’s more, his love pours out from him unconditionally, and is given to us, and everyone around him, in spades every day. This child has hurdles to overcome that we will never know, and every challenge in the world presented to him, and yet he’s the embodiment of affection. He is happiness. He is truly an angel. And lucky for us, he is all ours.