The Tweet That Sparked a Legal Revolution

Australia's defamation boom started with a 21-word tweet. In 2011, Mike Kelly, then the Labor MP for the federal seat of Eden Monaro, fired off a Twitter post criticizing the Liberal Party's pollsters, Lynton Crosby and Mark Textor. His misspelled expostulation, "always grate to hear moralising from Crosby, Textor, Steal and Gnash. The mob who introduced push polling to Aus," ignited a lengthy and expensive defamation action that would take Kelly to the High Court and back, outlive his political career, and markedly reshape the way large-scale defamation is litigated in Australia.

The case, known as Crosby, is a hinge point in Australian defamation history because it was initiated in the Federal Court, rather than a state or territory jurisdiction. This new approach led to much debate about whether it belonged in the Federal Court at all. Justice Steven Rares of the Federal Court ultimately decided that it could, and a costly side trip to the High Court confirmed his view. It was established that defamation cases could indeed be filed in the Federal Court, provided that the alleged slur was leveled on a mass-media or national platform.

The Rise of the Federal Court as a Defamation Fight Club

Post-Crosby, the Federal Court became a promising new fight club for litigants seeking to avenge injuries to their reputations. The court could hear cases in any capital city, and since 2005, defamation laws had been consistent across the country. Additionally, the Federal Court offered trials by judge alone, unlike state courts which were apt to empanel juries.

Juries can be a real banana skin for plaintiffs, especially if they are politicians or public figures with a controversial past. In practical terms, juries add duration and cost to a trial, because they need everything explained to them slowly and require regular breaks. This adds to the overall cost of litigation.

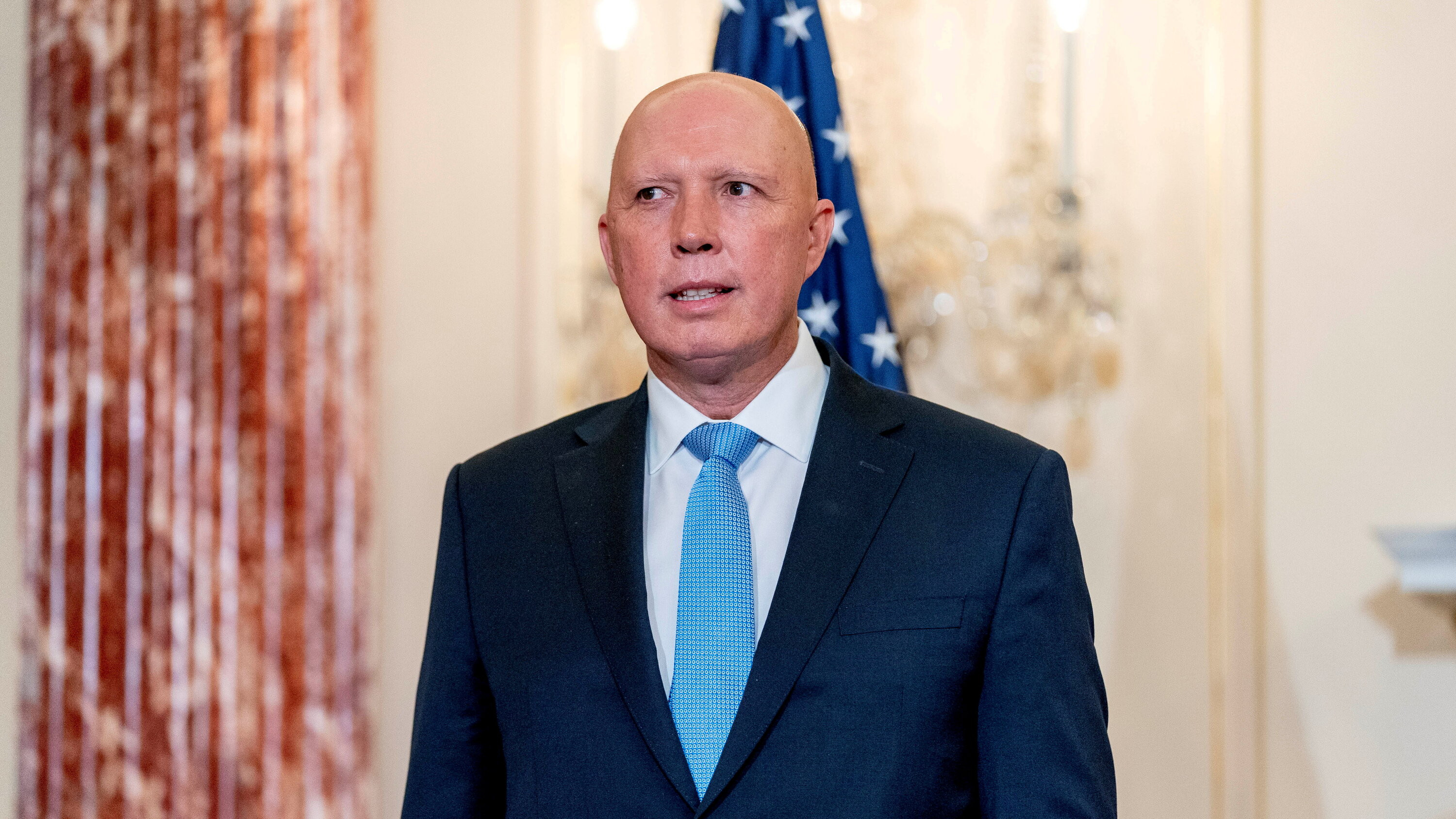

Joe Hockey, then Treasurer, was one of the first to utilize the new jurisdiction. In 2014, he extracted $200,000 from the Sydney Morning Herald for stories reporting on Liberal supporters making donations to a Liberal fundraising arm called the “North Sydney Forum” in return for access to the Treasurer. The actual articles were held not to be defamatory, but the newspaper was penalized for a poster headline and social media alerts using the phrase "Treasurer For Sale.”

While Hockey achieved a headline victory, much of his case failed and he ended up hundreds of thousands of dollars out of pocket. But he insisted he had no regrets, stating, "After nearly 20 years in public life I took this action to stand up to malicious people intent on vilifying Australians who choose to serve in public office to make their country a better place."

The Defamation Boom Takes Off

The visuals of an aggrieved individual winning satisfaction, even if the victory was costly, attracted new clients. From Hockey's case onward, the number of defamation cases filed in the Federal Court soared. In 2016, six defamation actions were commenced in the Federal Court. By 2020, that number had leaped to 67.

Dr Matt Collins, then Victorian Bar president, addressing the National Press Club in late 2019, disclosed his own audit revealing that on a per capita basis, New South Wales now had 10 times the defamation cases heard by superior courts than London – once known as the libel capital of the world. Collins called for a wholesale review of defamation in Australia, including the shifting of the onus of proof from defendants to plaintiffs.

Collins believes the burden of proof in Australian defamation law is backward. "In every other area of law, we put the burden of proof on the plaintiff. Whether you're complaining of misleading and deceptive conduct, or trespass, the onus is on you to prove that the offence has been committed. But in Australian defamation law, it's the other way round — the respondent has the burden of demonstrating that what they have said or published is true."

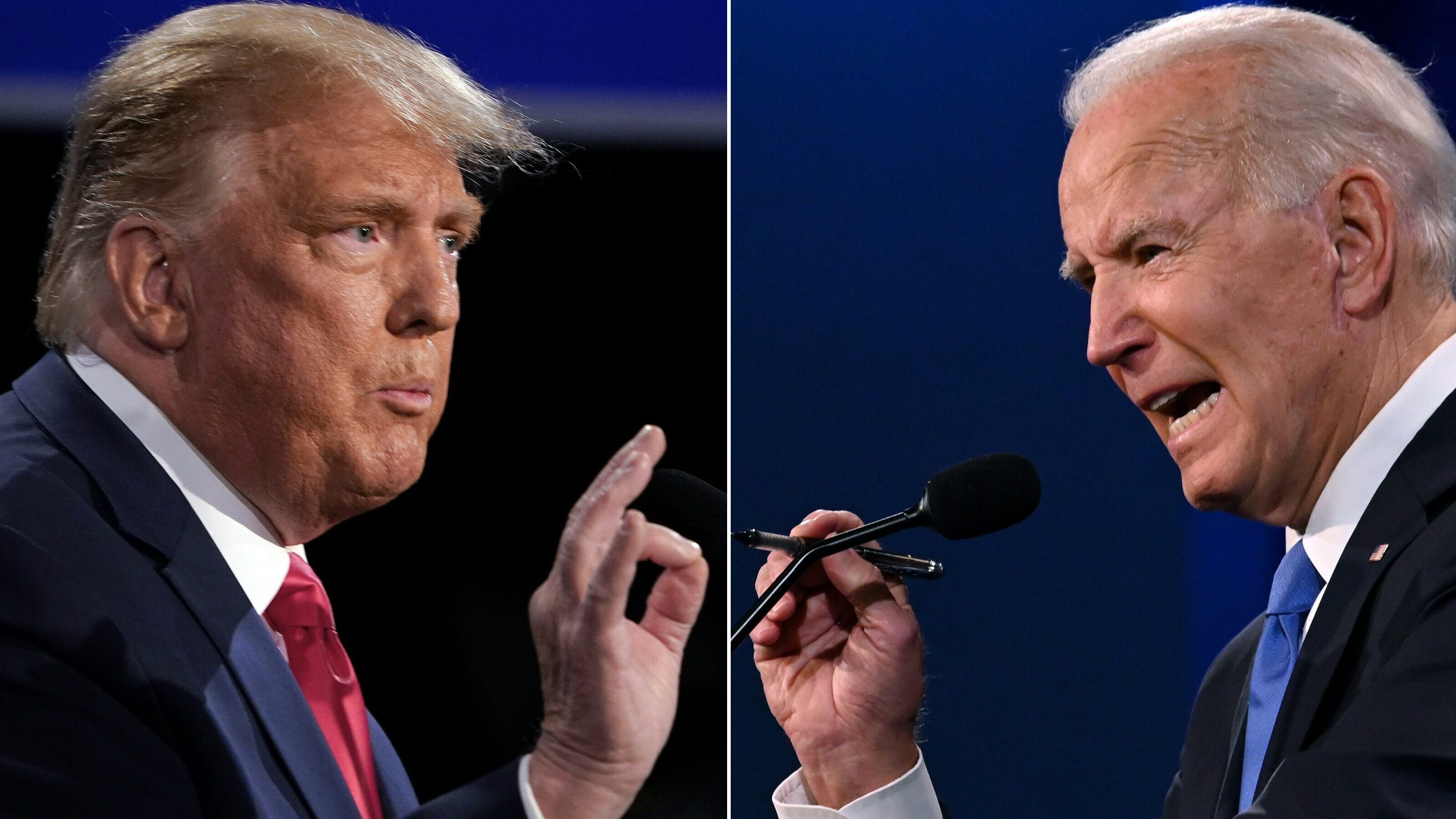

Learning from the US: The Sullivan Case

In the United States, the 1964 Sullivan v The New York Times case flipped the onus of proof to plaintiffs. The Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment right to freedom of speech established a presumption towards publication that it was the aggrieved party's duty to displace. This was a significant shift in the legal landscape for free speech in the US.

The publication at the heart of Sullivan was an error-strewn ad placed in the Times by civil rights leaders raising money for the legal defense of Martin Luther King. The ad made claims, some accurate and some inaccurate, about the persecution of Black students in Montgomery, Alabama. The case was brought by public officials in Alabama, where there was a pattern of litigation against northern publications reporting sympathetically on the civil rights movement's battles in the South.

The Shift in the Australian Defamation Landscape

In Australia, by 2018, high-value plaintiffs were experiencing considerable success in obtaining hefty sums of money from newspaper publishers and broadcasters. The best-known instance was the record $2.87 million payout to Hollywood actor Geoffrey Rush. Justice Michael Wigney’s judgment in that case was a scathing repudiation of the Daily Telegraph's front-page story alleging that Rush had sexually harassed his onstage daughter.

Other high-profile cases followed, with business figures and politicians securing significant damages. Chau Chak Wing won $280,000 from Fairfax and then $590,000 from the ABC, both arising from reporting on the Chinese-Australian billionaire’s political influence. Businesswoman Elaine Stead won $280,000 from the Australian Financial Review over questioning of her acumen. Papua New Guinea’s foreign minister William Duma won $465,000 from Fairfax in 2023 over a story linking him to a corruption probe. Former NSW deputy premier John Barilaro secured damages of $715,000 against Google – the owner of YouTube – over two videos made by Australian comedian Jordan Shanks.

Defamation Law Reforms: A Shift in the Tide?

In response to the surge in defamation cases, the Standing Council of Attorneys General (SCAG) agreed to enact a slate of defamation law reforms in 2021 designed to even the scales for publishers. These reforms were adopted by every jurisdiction except WA and the Northern Territory. They established a “new” defense of public interest, some clarification on capped damages and on the limitation period for actions, plus a new “serious harm” test aimed at weeding out frivolous cases.

The Reality TV of Defamation: The Federal Court Livestream

The emergence of the Federal Court livestream has added a new and often thrilling dimension to the defamation landscape. Anyone with an internet connection can now witness the unfolding of these legal dramas and access details that might not have been published in the traditional media. The live broadcast of trials has created a brand new and often genuinely thrilling form of reality TV.

The two highest-profile defamation cases of the past year – decorated war hero Ben-Roberts Smith’s tilt against Nine Media and Bruce Lehrmann’s defamation suit against Ten, News Corp, and the ABC – delivered public defeats for plaintiffs. Both cases were covered extensively by the media and streamed live on the Federal Court’s website.

The Gender Divide in Defamation Litigation

There is a perception that men are more likely to sue in defamation than women. Some practitioners theorize that this is because men have historically held more senior positions and therefore have more to defend in terms of reputation. Others argue that men are more likely to be accused of crimes and therefore more likely to be the subject of defamatory allegations. However, there is no concrete data to support either of these theories.

Comprehensive statistics on defamation cases are difficult to obtain. Some cases are settled out of court with no formal record. Others can drag on for years with decisions being appealed and reversed. It's a hot mess statistically speaking.

The Value of Reputation: A Gendered Perspective

Defamation law is designed to protect individuals from unfair and injurious publications. However, the way it is applied in practice is influenced by societal prejudices about what is worth protecting. It seems that the worst insult you can level at a man is that he is corrupt or a sexual predator. For women, the biggest payout was to Rebel Wilson, who was accused of lying about her age. This suggests that reputational harm is perceived differently for men and women.

The Future of Defamation Litigation

As Australia's defamation boom recedes, it's notable that politicians remain a popular group of plaintiffs. As faith in politicians declines, is it possible that they are increasingly resorting to the courts to referee their disagreements? To provide vindication when the parliament cannot? To litigate culture wars through the courts rather than the parliament?

Politicians have the freest speech of any Australians; their workplaces are parliamentary chambers inside which they can literally say anything they like. While they are entitled to use the courts to litigate over remarks made outside the chambers, the rising number of political defamation cases begs the question of whether the courts are the right venue for resolving such disputes.

The Last Word

The defamation landscape in Australia is complex and constantly evolving. The rise of the Federal Court as a new battleground for reputations, the influx of high-profile cases, and the introduction of reforms aimed at balancing the scales for publishers have all contributed to a dynamic and unpredictable legal landscape. The future of defamation litigation in Australia remains uncertain, but the trend towards caution amongst plaintiffs suggests that the legal landscape may be shifting.