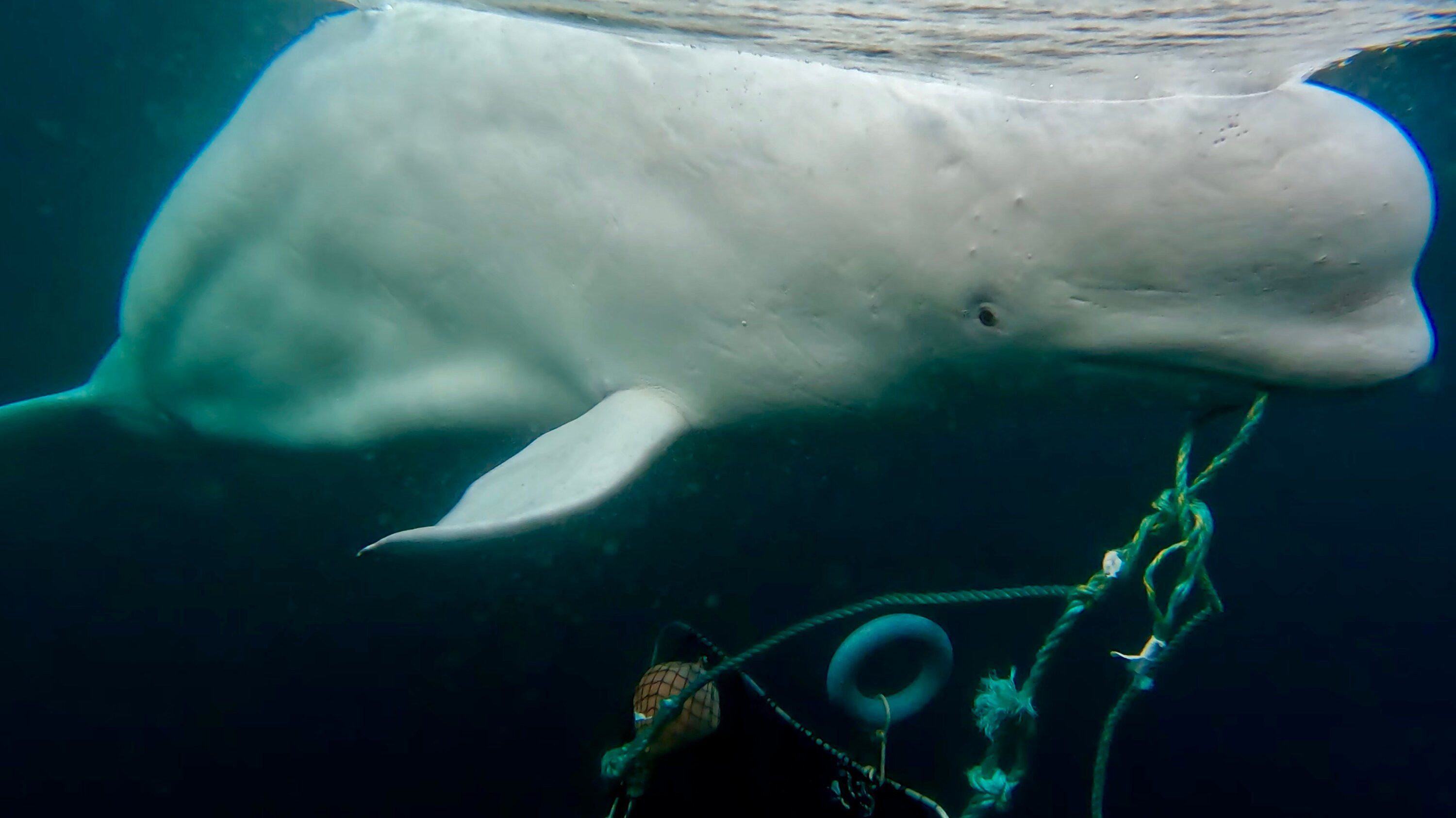

At the desert oasis of Bitter Springs, tourists float lazily through water so clear it reflects the piercing blue sky. Ringed by a rare palm forest, this spring, near the town of Mataranka, is a must for those on a road trip between Darwin and Alice Springs. But there are fears these thermal pools and the nearby Roper River, famous for barramundi fishing, are under threat. Water levels are dropping. And if it dries up further this oasis may not survive a bushfire.

These rivers are the lifeblood of the Northern Territory, fed by springs and an ancient network of groundwater. It's water the NT government is giving away for free. Giant new water licences are being handed out to developers, in search of the next boom crop. And a new lucrative, but controversial, player has entered — cotton. Not that it's always mentioned.

"I think there is a sense that cotton is a dirty word and that we don't mention it if we don't have to," says Kirsty Howey, executive director of the NT Environment Centre. Not mentioning cotton appears to be part of a broader effort to avoid a public backlash, as the NT government helps smooth the regulatory path for this crop.

That's led to allegations of cosy deals, silencing experts, ignoring traditional owners and the government tolerating false statements on official documents. "We can't afford to make the same mistakes that have been made in the Murray-Darling basin," says Jenny Davis, a freshwater ecologist from Charles Darwin University. "I feel as though we are just going headlong down that path."

Growing Cotton on Pastoral Leases: A Legal Gray Area?

One station not mentioning cotton, but growing plenty of it, is Dry River, near the regional centre of Katherine. It's owned by the Paspaley family, who pioneered pearling in northern Australia. Satellite images and drone footage shows Dry River Station has been growing irrigated cotton for the past two years — helped by free water that would be worth around $15 million in the Murray-Darling Basin. This is despite saying on their land clearing applications they would be planting hay. It's the same story on the station's water licence, where hay was the only crop mentioned.

Dr Howey says that is "not OK." "If you want to grow cotton, you need to say it on your water license application. You need to say it on your land clearing application," Dr Howey says.

One reason station owners may be reluctant to mention cotton is that it's mostly grown on what are called 'pastoral leases' — public land leased out to graze cattle on. "Nothing more, nothing less," says Tony Young, a former chairman of the NT Pastoral Land Board, which oversees these leases on behalf of the government. "It would be unlawful. In other words, a breach of the lease terms, to grow commercial cotton," says Mr Young, who is also a former judge.

Despite encouraging the industry to grow in the Territory, the minister for Environment and Water Security, Kate Worden, concedes she's never asked if it's actually legal to grow cotton on a pastoral lease. "They can grow crops as they see fit, the Northern Territory government doesn't tell farmers what they can grow," Ms Worden says.

Dr Howey has received legal advice. "It is not lawful to grow cotton on a pastoral lease in the Northern Territory," she says. She's already challenged this practice once in court. That prompted a tactical retreat from the station owner, who withdrew the land clearing application. Given that case wasn't resolved by a court decision, Dr Howey says she's "carefully considering" another challenge.

That would be a major blow to the NT government, which sees cotton as a big part of its strategy to double the agricultural sector to $2 billion by 2030. And it leaves a major legal cloud over the industry, even as millions are spent on the NT's first cotton gin, which opened in December outside Katherine. Dry River did not respond to questions from Four Corners.

A Creative Loophole: Feeding Cotton Seed to Cattle

One station has come up with a creative way to overcome the legal uncertainty of growing cotton on a pastoral lease. Malcolm Harris says he's growing cotton at the NT's Ucharonidge Station to feed the seed to his cattle. By this reckoning the lint is just a by-product.

To former judge Tony Young, this argument is "highly implausible." Dr Howey says it's "bordering on ridiculous." "Yes, you can feed cotton seed to cattle, but that is not the primary reason that you grow cotton. You grow cotton to sell it as a crop," she says.

The industry's peak body says cotton seed makes up only 15 per cent of the crop's value. Even Environment Minister Kate Worden, when asked if the primary purpose of growing cotton was to feed the seed to cattle, replied, "Absolutely not." Such an admission could be problematic for cotton growers as this argument has been used right across the Territory.

Dr Howey says it was previously understood that farmers wanting to grow a crop like cotton needed to apply for a non-pastoral use permit, but farmers stopped applying for these a few years back. Those permits require native title holders to be notified about the change in land use. Harold Dalywaters is an elder and one of the traditional owners of the lands covered by Ucharonidge Station. He says he was never informed about the planting of cotton or the clearing of land. "It's a shame … the pastoralists just went on and done it," he says. "As traditional owners, when things happen to our land, myself and my family, we suffer emotionally, physically, and it's like a cancer that lives in you."

Tony Young says native title holders are being deprived of their "right to be notified, the right to negotiate, the right to seek compensation and compensation may be a very significant amount." Four Corners put questions to Malcolm Harris, but he did not respond.

The Promise of Rain-Fed Cotton: A Watery Reality Check

The cotton industry has often argued it's not a threat to the NT's water resources, as much of the northern crop is grown without irrigation. "There's a lot of mistruths around cotton … the public [should] understand 95 per cent of cotton grown in the northern territory is rain fed," Ms Worden says. But with variable rain during the wet season and the long dry, the industry is eyeing off plans for irrigation and the big water licences handed out by government recently.

Outside the tourist town of Mataranka, melon and mango farmers have been irrigating for the past 10 years. Their water is drawn from the same aquifer that feeds Bitter Springs and the Roper River, and scientists warn the impact of these licences is already being felt. Professor Matthew Currell, a hydrogeologist from Griffith University, says groundwater levels in the Mataranka area have been steadily declining. "I think it's clearly a result of the additional extraction that's occurring for those farming operations," he says.

If the water level drops further, he fears the rare palm forest that surrounds Bitter Springs could be destroyed in the next major fire. "These Livistona palms need groundwater within about a meter of their root system. Otherwise, they become really vulnerable to the fire and they dry out and potentially could be lost in a big wildfire," Professor Currell says.

Mangarrayi woman Cecelia Lake's family are traditional owners around in the Mataranka area. She's noticed the water levels around the springs and Roper River changing. "Ten years ago we'd go out fishing, we'd just walk along the riverside and just pick up, just scoop up the water with the Billy can … But as the years passed, we noticed water levels were dropping," she says.

Larrimah: A New Precinct, A New Water Grab?

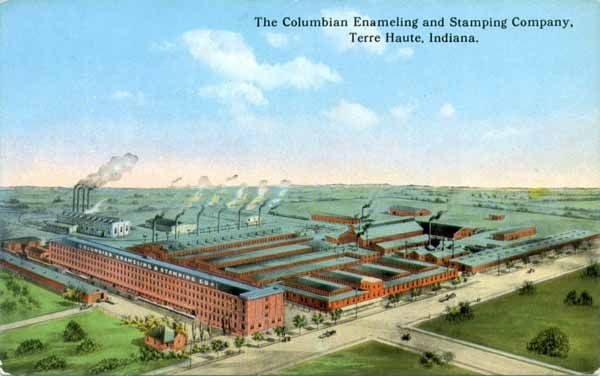

Despite worrying signs that water levels are already falling, there are plans for a major new agricultural precinct just down the road in Larrimah. In 2020, a quasi-government entity called NT Land Corporation released 5,700 hectares of land that it said was suitable for crops like melons, citrus and mangoes. The land, which requires clearing and development, came with a 10,000 megalitre water licence.

This licence will draw water from the same aquifer that feeds the Roper River and Bitter Springs. To justify giving away so much water, the government massaged the science. It changed the rules and effectively moved a boundary line which divides the wet "Top End zone" from the dry "Arid zone." Suddenly, the area's new farm would have access to a whole lot more water. When the decision to issue the licence was challenged, an independent panel found it should never have been granted.

"We would've expected the government and the department to take that one on the chin to accept the umpire's decision," Dr Howey says. Instead, the government dismissed the panel's decision and said it was determined to see the licence to go ahead. It maintains water extraction from Larrimah will not affect the springs, and says groundwater levels in the area are not declining.

When the farmer developing this new precinct, Jamie Schembri, resubmitted the water licence application in June, it revealed his true plans. There would be hay, mangoes and melons, but the largest crop would be 800 hectares of irrigated cotton. Mr Schembri declined to be interviewed but did explain why farmers can be reluctant to mention cotton. Whenever you do, there's a backlash, he said.

A Political Hot Potato: Water Policy in the Election

Territorians go to the polls this weekend but there's almost no difference between the major parties on water policy. Minister Kate Worden says outsiders need to come to the NT and understand its weather and water systems before criticising. "Maybe [then] we'll have a listen to what you've got to say. But if you're outside the territory, stop making comments about the Northern Territory," she says.

Cecelia Lake says the message from the environment could not be clearer. "The water is crying out for help. We're crying out for help. We feel that the water and us are connected and that we're both crying for help to make the government listen to us. The water they've already taken is enough. Please don't take any more from us."

Cotton's Unclear Future: A Race Against Time

The NT government's gamble on cotton as a "silver bullet" for economic growth is facing mounting pressure from environmentalists, traditional owners and scientists who warn of the devastating impact it could have on the region's unique ecosystem. The fight over water and the future of the Top End's iconic springs is far from over, with legal challenges and community concerns looming large as the NT heads to the polls.