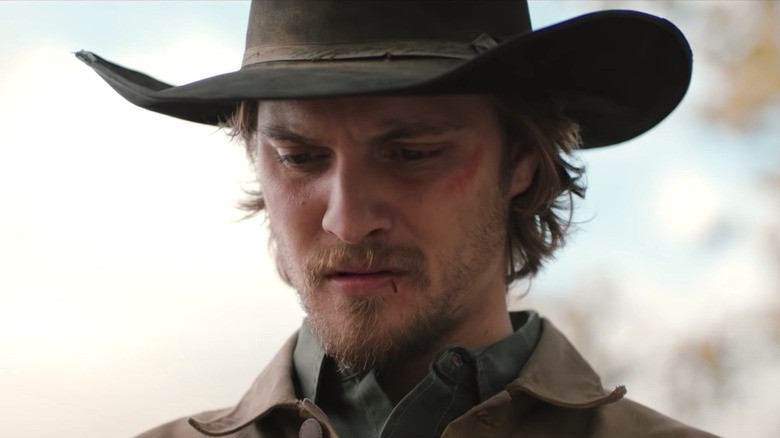

When I read back in the spring that Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance was the most divisive movie at Cannes—it got the festival’s longest standing ovation (11 minutes) and the award for best screenplay, while also occasioning multiple midscreening walkouts—I thought I knew which side of the divide I would fall on. An over-the-top body-horror thriller about an injectable drug that allows a fading star to swap bodies with a younger, hotter woman who is almost but not quite her? With gnarly special effects achieved mainly via prostheses and makeup rather than CGI? Directed by a middle-aged woman? Lay it on me, especially if it stars Demi Moore, the Brat Packer turned Hollywood fixture of my cinematic youth, in what everyone is saying is the role of a lifetime.

The premise sounded familiar, sure, but the movies it evokes are all enduring classics of the horror genre: John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, David Cronenberg’s The Fly, John Carpenter’s The Thing. So I went into The Substance hyped for, at the very least, some down-and-dirty pulp thrills. And if I was lucky, Fargeat’s sophomore feature might be as primally cathartic as those reliable nightmare-generators. Like them, it revolves around the fear of biological transformation into something horrifyingly other: an uncanny younger double, a man–fly hybrid, a human head skittering about on spider legs. In the case of The Substance, though, the object of horror is simply a woman who has reached the shriek-inducing age of 50—a feminist twist that struck me as original and witty, not to mention long overdue.

I’m disappointed to report that I found The Substance lacking in both departments: the oh-no-they-didn’t gross-out quotient and the intellectual heft. The fleshly transmogrifications the viewer witnesses, again and again, as Moore’s Elisabeth Sparkle injects herself with the glowing yellow-green “substance” for her weekly identity swap with Sue (Margaret Qualley) grow more and more abjectly disgusting as both women’s physical and moral conditions degrade. But the fact of the switch means the same thing each time: Elisabeth has sold her soul, and her last chance at earthly happiness, to cling to the illusion of eternal youth, all in the service of a cruel and insatiable patriarchy. After two hours and 20 minutes of flamboyantly repulsive variations on this well-worn theme, even the strongest-stomached and most feminist of viewers could be excused for muttering, We get it already.

Elisabeth, once a celebrity big enough to earn a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (though she seems to have been known primarily as the host of an aerobics show), fears getting old so much that she signs on to an obviously Faustian bargain proposed by a mysterious smooth-faced stranger: For seven days of every 14, she will continue to live in her own less than youthful but still fit and gorgeous body, in the glamorous high-rise apartment paid for by her lengthy career as America’s official Hot Girl. For the next seven, that self will go into a comalike state of hibernation, nourished with food from a tube, while the impossibly attractive Sue assumes the hot-girl mantle, hosting a revamped version of the same TV show in a skimpier bubblegum-pink leotard.

A representative from the never-named company that provides the Substance periodically reminds the women that they are two different manifestations of the same being, so any deviation from company rules will end up harming them both. But the relationship between Elisabeth and Sue—who, because their bodies share a single consciousness, never see each other in a waking state—soon becomes a ferocious rivalry, as each tries to wangle a few extra days of embodiment, or to take revenge on the other by leaving figurative and literal messes for her to clean up when her week rolls around.

Nothing in the foregoing description would preclude The Substance from being a good or even great movie. What made it so tedious and grating, for me, was not the concept but the execution. Fargeat approaches her material with a hatchet, hacking methodically away but rarely sculpting with any nuance. Fans of The Substance may object that her bluntness is a deliberate style choice, and the filmmaker would no doubt agree. But setting style aside (to the extent that that is ever possible), what exactly are the ideas at play in The Substance? If the film is meant as a social satire, it’s hard to discern its target, other than an abstract notion of oppressive “beauty standards” in which neither the beauty industry nor social media plays any significant role. The entertainment industry comes into focus only glancingly, personified by a single seldom-seen character: Elisabeth’s (and later Sue’s) boss, a piggish TV executive unsubtly named Harvey and played by Dennis Quaid. Harvey is shot mainly in tight close-up through a fish-eye lens, his face warped into a monstrous mask. Stuffing his face with luridly pink shellfish, he unceremoniously fires Elisabeth before turning his pervy leer on the more nubile and compliant Sue.

I’m not asking for a detailed character portrait of Harvey the lecher, but after two or three scenes establishing that he is a sexist boor, the character’s presence becomes nothing more than a drag. Similarly, the many scenes in Elisabeth’s futuristic all-white bathroom in which the women enact the series of procedures that will enable them to switch places all started to blend together in my mind. The devolutionary logic of body horror demands that each successive body switch be more horrendous than the last, with the fast-aging Elisabeth acting as the portrait of Dorian Gray, while Sue serves as the preternaturally radiant real-life Dorian. There is no shortage of repulsive and sometimes darkly funny imagery as we watch these two symbiotic beings disintegrate in unison. But with their characters and the story as a whole remaining more or less static during the scenes in between, these moments of metamorphosis ceased to scare or shock me. Instead I started to resent the movie’s self-satisfied posturings, the way it kept proudly trotting out twists any viewer reasonably versed in film history could have seen coming.

At a highly pitched emotional moment near the end, the score (by the one-named composer Raffertie) references one of the most famous music cues in cinematic history: the spiraling love-and-death theme of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Vertigo, adapted from a similar leitmotif in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Just as was the case when Michel Hazanavicius used that cue in the soundtrack of his silent-film pastiche The Artist, the effect is to take anyone who’s seen Vertigo directly out of the experience of watching the movie in front of them and make them start ruminating about why any filmmaker in their right mind would lift such a familiar theme. A later snippet from Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spake Zarathustra” makes similarly clumsy use of a musical passage universally associated with 2001: A Space Odyssey. Is the intention here to parody the films being sampled, to pay them homage, or simply to goose the audience’s attention with an easily recognizable burst of music pre-laden with emotional significance? Fargeat makes it hard to tell what these borrowings are meant to accomplish, besides hitting us over the head.

Though I disliked it with a passion, The Substance, unlike some other feminist thrillers of recent years (Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman comes to mind), is not a pernicious or reprehensible movie. It never sends a message opposite to the one it intends to convey, and that message—about the emotional and corporeal violence of societally reinforced female body dysphoria—is a timely and urgent one. If anything, the problem is that the message and the vehicle used to convey it are too much in sync. Fargeat’s clobbering approach leaves no space for the audience to speculate, to make our own connections and discoveries.

I will concede that the casting of Demi Moore was a masterstroke on Fargeat’s part, given that actress’s reputation for pushing back on body-related taboos. Moore was, to my memory, the first celebrity to pose nude for a magazine cover while pregnant, and later made the then-bold move of shaving her head and building a muscular physique to play a soldier in G.I. Jane. Moore’s lived experience of fame is far more interesting than that of the hazily defined superstar she’s playing, and in the few scenes where Elisabeth gets more to do than react with horror to her latest mutation, Moore explores the bottomless anxiety of a woman whose self-worth depends on maintaining a flawless exterior. One of the rare scenes not to depend on gory effects for its drama shows Elisabeth sabotaging herself as she readies for a date with a former high-school classmate: She puts on a full face of makeup, smears it off, reapplies it in a different style, then stares critically in the mirror as the time set for the date ticks past. That moment is poignant, and the break from the Grand Guignol is welcome, but the movie soon ramps up to its former visceral intensity, all squelchy wounds and necrotic extremities. As for Margaret Qualley, while her dance background gives her exercise-show scenes a convincing kineticism, Sue gets even less character development than her older double. In close-up shots that appear intended to reconstruct the male gaze on Sue’s twerking nether parts, Fargeat’s camera—the cinematographer is Benjamin Kracun—does its own fair share of narratively pointless ogling.

I haven’t read much coverage of The Substance since its initial reviews at Cannes, but I have the feeling I will be in the minority in my response to what seems to be a general crowd-pleaser. If, like most of the body-horror classics it channels, this movie had clocked in at under two hours, I might have experienced it as the gritty exploitation flick it seemed to want to be, but at 140 minutes, it felt endless and repetitive. When Elisabeth and Sue, or whatever organic matter remained of them, met their final fate (with the help of some spectacular makeup effects from Pierre Olivier Persin), my main sensation was one of relief that my sufferings, not theirs, were over. If ooky Cronenbergian horror filmed with unremitting forcefulness is your personal cup of tea, or addictive syringe of neon-yellow liquid, please enjoy. Just don’t try to convince me that this leaden message movie actually has anything interesting to say.