Eli Myers was only 15 when his close friend and classmate Chloe Kreutzer died from taking a counterfeit Percocet pill filled with fentanyl. Initially, he said, the response from officials at his Los Angeles high school was stony silence. Even years later, the information he and his classmates got about the risks of fentanyl poisoning amounted to little more than a droning lecture in health class, he said.

The same thing happened at Kyle Santoro’s northern California high school, when a student was found overdosing in a bathroom and was revived by the principal with Narcan. “Our school never talked about it,” said Santoro, who said the student had just disappeared from campus and most students never even knew what happened.

Faced with an information void, Myers and Santoro took matters into their own hands. Today they’re part of a growing cadre of teens stepping up to educate their peers on the dangers of fentanyl, at a time when teen overdose deaths have skyrocketed to all-time highs, often caused by fake pills spiked with the super-potent synthetic opioid.

For both teens, film has been their medium of choice. In 2023, Santoro produced a feature length film, Fentanyl High, a somber documentary that interweaves the stories of parents who have lost kids to fentanyl, young people who have survived addiction and expert voices on how to combat the problem. Santoro, now 18, works with health officials to hold educational screenings and discussions around California.

Myers, also 18, led his classmates in turning an advanced video production class project into a film warning about the dangers of fentanyl that was shown at a school assembly this year. After Chloe’s death, Myers said, he felt “like a ghost”, seeing her face in every corridor. “So that inspired me to become an advocate, spreading the word that this is something that’s a real problem.”

They are not the only ones. A team of student newspaper reporters at Carlmont high school in the San Francisco Bay Area created a multimedia journalism project about the 2021 fentanyl death of their classmate Colin Walker, who took a pill he bought on Snapchat at bedtime and never woke up. The project is now being used by health educators around the US as a resource for teens.

In Washington state, Nathan Pan and Tanisha Kshirsagar of Skyline high school dedicated their senior year to creating a public service announcement warning about fentanyl dangers. They told a local television station that, although their school is still traumatized by the deaths of two 16-year-old boys from fentanyl overdoses in 2019, drugs and overdoses are still “kind of a taboo topic” at school.

Perhaps the best known anti-drug effort was the Just Say No campaign started by Ronald Reagan’s presidential administration in the 1980s. The campaign featured scare tactics and ultimatums, such as an ad that showed frying eggs as an analogy for “your brain on drugs”. The whole program has since been proven by multiple studies to have been a dismal failure.

But these days, experts warn that taking a hands-off approach to drugs can be equally problematic. “In this country, we’ve kind of gone from ‘just say no’ to ‘just say nothing’,” said Ed Ternan, who started the drug education organization Song for Charlie after his 22-year-old son died after taking a fake Percocet pill. “To some degree, young people are dying from a lack of information.”

The fentanyl crisis has brought a terrifying irony to the American high school experience: the number of young people dying of overdoses is on the rise, even as teens today are far less likely to use drugs than previous generations.

A 2024 study found that drug-related death rates among 14- to 18-year-olds doubled between 2019 and 2022, killing more than 3,000 teens over three years. But the study found that in 2022, only 8% of high school seniors reported having used an illicit drug other than cannabis in the previous year, compared with 21% two decades earlier.

That’s because trying illicit drugs has now become much more deadly, the researchers said. Experts says that today’s teens are more likely to try things they think are safe, such as pharmaceutical products they can easily obtain from friends or buy on social media, rather than drugs like heroin or meth.

The problem is that the drug market has been flooded with pills made to look just like real pharmaceuticals, including Xanax, Adderall and Percocet. But what they actually contain is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, so potent that just a few grains of white powder can be deadly.

“The drug supply is very dangerous,” said Dr Scott Hadland, the chief of adolescent medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, who has authored research on youth overdoses and how to prevent them. “Teenagers might be seeking pills that they don’t realize are counterfeit and don’t realize contain fentanyl. They might be seeking them out because they’re struggling with underlying symptoms of anxiety or depression or pain and they think pills are going to help with those symptoms.”

The lesson of the past is that ignoring the problem or scolding people doesn’t work. One of the best preventative measures, Hadland said, is having modern drug education programs for teens. But researchers, drug education advocates and teens all agree that such programs have until recently been sorely lacking in the schools.

Santoro, who is graduating high school in June and heading to Ohio State University, said school policies need to emphasize listening and truth-telling over cracking down on drug use. “Disciplinary actions or zero-tolerance policies are actually feeding the risk, because [school officials] are not listening to kids about why they are using in the first place,” he said.

For Santoro, the most transformative part of making Fentanyl High wasn’t the film itself, but the conversations it started. Every educational screening, offered at schools, community theatres and public health departments, includes a discussion among parents, kids, health officials and educators, which he describes as a “social hack” that can open the floodgates of communication needed to address the teenage fentanyl overdose crisis.

Sometimes these conversations aren’t even about drugs. He remembers a recent post-film discussion where a father and daughter tearfully shared the difficulties they were having keeping positive communication alive while the parents were going through a divorce. The revelations led the group to a larger discussion about healthy ways to cope with painful situations, but just talking openly about it seemed to help a lot.

“The program is trying to bring humans together with humans,” he said. “It’s really showing that there is a community and that there is hope.”

Myers, who graduated in the spring and plans to become a college therapist, said drug education talks need to include real safety facts, including information on how the opioid reversal drug Narcan can be used to revive someone who is overdosing. “I think people are scared to talk about it, especially if they think they’ll get in trouble for it,” he said. “But the more we talk about it and the less stigmatized it becomes, the more people can do about it.”

Every generation has its drug prevention slogan. But with the rise of deadly fentanyl, it's time for some new words of caution:

It only takes one.

It only takes one fake pill laced with synthetic fentanyl to kill. And fake pills are widely trafficked—even masquerading as safe prescription drugs.

It's a new era in the fentanyl crisis, and young people are especially vulnerable. Overdose deaths among adolescents 10-19 years old more than doubled between 2019 and 2021. Seven out of every 10 fentanyl pills seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) contains a lethal dose.

With this increasingly widespread threat, it is time for parents to incorporate a new message in their back-to-school conversation with children of all ages: It only takes one.

Fentanyl is not your parents' street drug. Dangerous pills are identical in size, color and markings to prescription medications, making it impossible to gauge safety just by looking. Young people are dying of fentanyl overdose who think they are taking Xanax to help them sleep, Adderall to study, or Percocet for pain relief after an injury.

It's killing kids who borrowed a pill from a friend or bought one online. Fentanyl can be found in recreational drugs commonly ingested by teens, including joints and vapes.

As the first ladies of Virginia and New Jersey, we have seen fentanyl's deadly impact in communities in every part of our states, and we can confirm that no area, no family, is immune.

New Jersey resident Max Lenowitz died on his 25th birthday after taking one pill he thought was Xanex. “My family didn't know much about fentanyl, nor did we know counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyl were so easily acquired and shared among their peers,” said his mother Patrice. “One pill killed our son.”

Organizations like Song for Charlie have pointers that parents can use to start “The New Drug Talk” with children of any age. In addition to stressing that young people should never take a pill they receive from a friend or purchase on social media, it's also important they learn how to recognize and respond if a friend is experiencing an overdose. Overdose-reversal medication naloxone, commercially known as Narcan, is now available in every state without a prescription.

Naloxone saves lives. Earlier this year, we joined first spouses from across the nation in a training session to learn how to administer naloxone, and we are coordinating with parents and teachers to hold trainings in our states as the school year gets underway. Check your governor's or state health department's website to find resources in your state, or check out state-based organizations like Virginia Fentanyl and Substance Awareness. Its founder, Karleen Wolanin, is one of thousands of parents using their own hard-earned experience to help others.

“After nearly losing my child to fentanyl and enduring over a decade of struggle, I've learned the vital importance of uniting our communities,” said Wolanin. “By channeling our pain into action and raising our collective voice, we can expose the true dangers of fentanyl and ensure that no one fights this battle alone.”

Just as it only take one mistake to take a life, it only takes one person, one conversation, to save one.

Parents, grandparents, teachers, coaches and mentors: As we head into a new school year, please take five minutes to have a candid conversation with the young people in your life.

Make sure they understand: It only takes one.

Suzanne Youngkin is the first lady of Virginia. Tammy Murphy is the first lady of New Jersey.

New Jersey and Virginia are among several states taking action to raise awareness and connect more individuals with treatment options. Governor Phil Murphy declared July 14 as Fentanyl Poisoning Awareness Day to honor Max Lenowitz' memory. In 2023, Governor Glenn Youngkin signed an executive order mandating state agencies take unprecedented and coordinated strides to combat fentanyl.

In 2023, drug overdose deaths declined for the first time since 2018.

While drug deaths remain unacceptably high –– at more than 100,000 last year –– at least we’re finally moving in the right direction.

But there is one slice of the population where deaths have jumped significantly: adolescents, teens, and young people.

Research shows that an average of 22 Americans ages 14 to 18 died from drug overdoses every single week during 2022.

Those researchers identified hot spots –– like Maricopa County, Ariz., and Los Angeles, Calif. –– where youth overdoses are highest.

Here, fake pills containing fentanyl have flooded the market. The pills are cheaper than ever and easily accessible on the social media platforms beloved by young people.

Our government has been trying to prevent young people from using drugs for more than a century. These campaigns have mostly involved scare tactics solely focusing on the consequences of drug use.

But while they may make for good commercials, such strategies usually fail as kids tune them out.

But in the age of fentanyl, we must trade fear-mongering for accurate and compassionate drug education based on science. Sadly, many states are failing to deliver.

Recently, I spoke with grieving parents and families who are fighting for robust and effective drug education and prevention. As a person in long-term recovery, I can sympathize. My own drug education was a failure.

Kids like me who grew up in the 1980s remember D.A.R.E. officers coming to our classrooms warning us about the dangers of drugs. It was the wrong message and the wrong messenger.

What we needed instead were practical tools and information that we could understand and identify with.

Thankfully, there are proven strategies to reduce the misuse of harmful substances. Take the hugely successful anti-tobacco (nongovernmental) Truth Initiative focused on young people. Truth worked because the campaign understood how teenagers think.

The goal was to craft a set of messages that never sounded preachy, that never condemned or blamed smokers; that told teens that Big Tobacco lied to them and then directed teens to rebel against it.

Young people who saw Truth ads reported being 66% more likely to say they would not smoke in the coming year.

We need a national Truth campaign for fentanyl. And it must start by understanding the nature of the problem we’re now dealing with.

Most young people who die from fentanyl do so after taking counterfeit pills.

Fake but deadly, these pills are pressed and shaped into popular medicines like oxycodone, Xanax, and Adderall.

Most have no physiological tolerance for potent synthetic opioids, so taking just one fake pill can prove deadly.

This is the new reality of taking pills in America and it means we must adapt to it.

The Drug Enforcement Administration wasn’t kidding when it launched the nationwide “One Pill Can Kill” campaign. The DEA’s slogan is concise and memorable.

But I’m worried that young people are still not hearing the government’s message, even if “One Pill Can Kill” is technically true.

Just as Truth ads understood they are competing with Big Tobacco, the DEA’s message is competing with a culture that tells all of us every day that there’s a pill to fix everything — that pills are a quick and easy solutions for what ails us. And this is a hard reality to undo.

To reach kids with a message that truly resonates, we must also think locally. For instance, The Wolfe Street Foundation program in Arkansas was the state’s first community-based youth recovery program designed for students in grades 7-12.

The program deploys a peer model, which means young people who’ve been impacted by substance use are also the program’s messengers. Wolfe Street recognizes that peers are crucial to getting young people to truly hear fentanyl warnings.

Parents still have an important role to play, too. I recommend parents visit the Ad Council, which offers advice for adults about how to talk to their kids about fentanyl.

Experts like Dr. Scott Hadland, a pediatrician in charge of adolescent and young adult medicine at Mass General Hospital and Harvard Medical school, says it’s crucial to be honest, compassionate, and open when talking with kids about complicated and hard subjects like drugs.

Stanford medical school recommends that drug education for young people focus on three key pillars: First, the curriculum must be scientifically based.

Second, it must be engaging and interactive because that’s how young people learn best. Lastly, it must be compassionate. Drug education ought to consider the fact that most young people will not try substances at all. And that’s good news.

But those who try them at some point are probably struggling with other aspects of life, like mental health, family stress, or some physical or emotional pain.

We live in a culture that celebrates quick fixes and pills for every ailment. That’s why saving kids from fentanyl is going to be an uphill battle that we all must fight together.

Ryan Hampton is a national addiction recovery advocate and author of the forthcoming book “Fentanyl Nation: Toxic Politics and America’s Failed War on Drugs” to be released by St. Martin’s Press on Sept. 24.

In Orange county, a former police officer spent years working with students and parents to prevent drug overdoses. When the fentanyl crisis hit, their work was tested in heartbreaking new ways

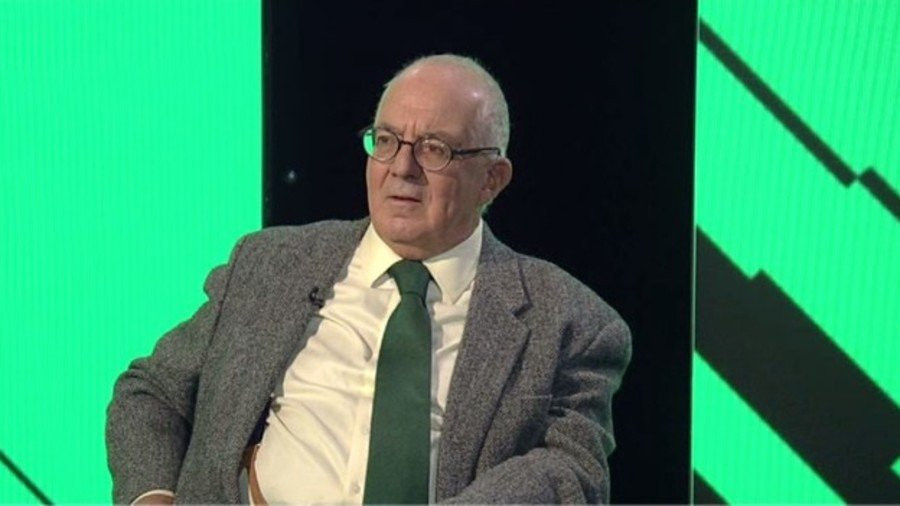

From his small, windowless office across from the teachers’ lounge at Dana Hills high school in Orange county, California, Mike Darnold has witnessed first-hand the rise of fentanyl as a brutal teen killer.

Darnold, 80, is a former police officer and recovering alcoholic. He’s spent the last 16 years helping save students whose lives have veered out of control because of drugs and alcohol. But it wasn’t until recently that his job became such an immediate life-and-death battle.

Before 2020, Darnold had rarely heard of students dying of drug overdoses. But since then, drug deaths – mostly caused by counterfeit pills spiked with fentanyl – have become one the leading killers of 14- to 18-year-olds nationwide. At Dana Hills high, there have been five deaths in the last four years alone.

One teenager was a popular and ambitious cheerleader in her junior year; another was a freshman football player. One was an incoming high school student who never made it to the first day.

Eddie Baeder could have been No 6. When Eddie first met Darnold last fall, he was only 14, getting ready to enter Dana Hills high as a freshman. But already, it felt like his life was spinning out of control.

Eddie loved football, baseball and wrestling and had a job at a dog daycare. He also had a tendency to want to escape difficult feelings, including grief over the death of his birth mother, who did not have custody of him but was still in contact, and the suicide of a close friend. At the time, the teen was deep into a tailspin of drug and alcohol abuse, throwing any kind of mind-altering substance he could find into his body, including vodka and whatever else his friends gave him.

“I was just looking for the next high,” he said.

Eddie is one of dozens of kids that Darnold has helped climb out of substance abuse. As high schools around the country scramble to set up education programs to cope with the rise in teen fentanyl deaths, Dana Hills high has been ahead of the game. Within these walls, Darnold has spent more than a decade devising ways for teens and parents to deal with the underlying issues that drive substance abuse.

To get there, he’s developed after-school programs that help teens find fulfilling alternatives to drug use, such as movie nights, beach parties and volunteering events. He also runs a series of workshops for parents that tackle one of the biggest barriers he sees when it comes to overcoming drug use: effective communication and boundary-setting with their kids.

Now, Darnold spends his days driving kids to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and organizing teen gatherings, in part because he wants to give back some of the wisdom and help he got overcoming his own alcoholism 44 years ago.

“It’s gratifying. I love it,” said Darnold. “I’m like the glue that brings it all together. It’s a good feeling to go to bed tired, because I’ve accomplished something.”

With its blocky 1970s architecture and sprawling athletic fields, Dana Hills high feels like a southern California idyll. The highly ranked school, with a student body of 2,000, sits in an upscale part of Orange county so close to the Pacific that it has a competitive surfing team and a year-long marine ecology program.

But Orange county has been a national hotspot for teen deaths from fentanyl-laced pills. Opioid deaths among youth aged 15-19 in the county climbed from fewer than six in 2019 to 33 in 2021 and 20 in 2022, according to county statistics published by the state.

It’s part of a tragic pattern playing out across the country. An average of 22 high school-aged teens died of overdoses each week in the United States in 2022, the most recent year for which statistics are available, according to a 2024 study by researchers from the University of California at Los Angeles and Harvard. The same study found that the overdose rate among high school-aged kids doubled between 2019 and 2022, the most recent year for which data was available – even though surveys show far fewer teens are using drugs than in previous decades.

Southern California was one of the first places to be hit with multiple teen overdoses from fake pills. The reasons for this are still emerging, but experts believe it’s partly due to the region being relatively wealthy, meaning young people have access to money to buy drugs, as well as its proximity to the border with Mexico, where much of the fentanyl supply is coming from. Overdose hotspots have recently cropped up in other parts of the country, including suburban Loudoun county, Virginia, last year.

“New hotspots are popping up all the time,” said Joseph Friedman, one of the researchers involved in the UCLA study. “Counterfeit pills are spreading and the drug supply is particularly toxic.”

That’s because fentanyl, a super-powered synthetic opioid, has made the nation’s drug supply far more deadly – even for those who experiment with just one or two pills. A few granules of the white-powdered drug can be enough to kill.

Fentanyl is largely made in Mexico with chemicals bought from China, experts say, and drug cartels are bringing vast quantities into the US. Since January 2024 alone, a California drug taskforce has seized almost 4,638lbs of fentanyl powder and more than 8.8m fentanyl-laced pills.

Young people aren’t exactly seeking out the drug; rather, they’re buying what they think are pills such as Adderall, Xanax or Percocet from friends or ordering them on social media sites like Snapchat and Instagram.

Illegal sellers often pack fentanyl into tablets that can look exactly like these pharmaceutical pills, and since there is no quality control, a single tablet can contain enough to kill an unsuspecting teen, who may think they are experimenting with safe prescription drugs. It’s the reason many prefer to call these deaths “drug poisonings” instead of drug overdoses, because the taking of fentanyl is often accidental.

“These aren’t addicts that are dying from fentanyl,” said Darnold. “These are kids that are dying because they tried one thing one time.”

This harsh reality rings true for Eddie.

At a party the summer before his freshman year, he said, his friend gave him some pills and the next thing he knew, he was on the floor getting CPR from an adult who happened to have the opioid-reversal drug Narcan. Once revived, he ran away before the ambulance arrived, he said. He now believes the pills were probably tainted with fentanyl.

His parents didn’t know about the incident at the time, but they knew their son needed help. They struggled on their own to get him into a series of live-in treatment programs. Then they heard about Darnold and the parenting class he was teaching at Dana Hills high, and swiftly signed up.

“Things were crazy and we were afraid Eddie was going to die,” said his adoptive father, Ben Baeder.

Baeder and his wife, Cynthia, took Darnold’s class, called the Parent Project, and learned a whole new way to interact with Eddie.

Darnold advises parents to share a lot of love with their kids, compliment their achievements, learn to listen and communicate without arguing. That might not sound revolutionary – but it’s often the reminder parents need when they’re frustrated and struggling to deal with their child acting out, and need help setting boundaries.

In tandem with these affirmations, Darnold says, parents should also create a clear set of rules on drug use. He advises they take strong action to intervene if they think their kids are using, such as making them take a drug test, and setting brief but hard-hitting consequences for their actions. These include removing all sources of enjoyment – phones, toys, television, electronics and even favorite books – for a limited time if a parent’s rules are being broken. In some cases, he counsels parents that the only thing to do is to send their child away to a live-in addiction recovery program.

“We don’t talk about disciplining kids,” Darnold said. “We’re providing opportunities for them to learn from their mistakes.”

As he got to know Eddie’s parents, Darnold also quickly built a strong personal connection with Eddie, who is now 15 and has been sober from alcohol and drugs for 11 months. Several times a week, often at 6.30 in the morning, Darnold gives Eddie rides to AA meetings. The other adults in the meetings have taken the teenager under their wings.

“Everyone sees a 15-year-old as like a mascot,” said Ben Baeder. “They remember their 15-year-old selves and wish they had gotten sober earlier.”

Eddie said he now sees how deadly what he was doing was. He never plans to go back.

“I found out what it actually means to be sober,” said Eddie, who describes Darnold as like a grandfather to him. “I figured out that if I kept doing what I was doing, I was going to die.”

By the time Amy Neville met Darnold, it was already too late for her son Alex.

In 2020, Alex Neville was 14 and, like Eddie, getting ready to enter Dana Hills high. He was a bright kid, who loved to skateboard and study topics like the civil war.

That summer, Alex admitted to his parents that he was taking oxycodone pills. His parents quickly made arrangements for their son to enter a live-in treatment program by the end of that week, Amy Neville said.

What neither Alex nor his parents knew was that the oxycodone pills Alex was buying on Snapchat were fake, and filled with fentanyl. Before the week was up, the parents woke to find Alex dead in his bedroom.

Since then, Neville has joined Darnold on the frontlines of preventing similar deaths. She has given talks to students at every grade level at Dana Hills high and dozens of other high schools around the country. She shows a film she helped produce that includes her son’s story, Dead on Arrival, explaining the dangers of fentanyl and fake pills.

“As the mom of a kid that died just trying to experiment, I wish I could shake you and make it real to you,” she tearfully tells students in the film. Alex “never intended for me to find him on his bedroom floor. He never intended for his dad to have to administer CPR while we were waiting for the paramedics. Alex never intended for me to see him wheeled away on a stretcher.”

Film screenings like these are the latest iteration of a community-led drug education push that began years ago in Dana Point, home of Dana Hills high.

Darnold works at the high school but is under a contract with the city government, which means he works with kids and families but doesn’t report directly to the school. Instead, he reports to Mike Killebrew, city manager of Dana Point, who has also long been involved in drug awareness efforts.

Killebrew remembers a pivotal moment about a dozen years ago. He was on his way to a breakfast meeting when he got a call from Darnold saying there was an emergency, and he needed to come to Darnold’s office at school. He arrived to find several students crying their eyes out. A classmate had died of an overdose. At the time, such deaths were rare – this had been perhaps the only overdose death at the school before the fentanyl crisis emerged.

The students had come to Darnold because they were determined to do something to prevent other kids from getting hurt by drugs. As a result, they launched Dana Point’s SOS club – short for Save Our Students – which gives teens opportunities to “hang out” and “party” that don’t involve alcohol or drugs.

The city-sponsored club is still highly active today, with Darnold helping its student leaders organize parties and outings, or community service activities like decorating floats for local parades and helping out at the city’s annual Concerts in the Park series.

“One of our mantras has been: a tired kid is a good kid,” said Killebrew.

All the interventions seem to have made a difference. The school has not had a drug death in two years.

Dana Hills high may be making progress, but the fentanyl crisis isn’t over. Overdose deaths remain stubbornly high across the US. The White House has urged schools to intensify their drug prevention efforts and to stock Narcan on campus to respond to overdoses. A new California law is requiring schools to develop overdose death prevention plans.

For Darnold, the solution won’t be as simple as stopping drugs coming over the southern border, or creating the perfect anti-drug campaign. He says the root problem is that people of all ages are seeking drugs as a quick fix to avoid facing their feelings. Young people in particular need more options for ways to feel good.

“Fentanyl is coming over the border by the ton and our kids are taking it,” he said. “But the problem isn’t Mexico. It isn’t even the fentanyl. The problem is we’ve got a whole bunch of people in America who are taking a lot of drugs. People take drugs because they want to change the way they feel.”

Sports, youth activities and service projects are all ways to address that root need, he says.

“What we’re doing is going all out,” he said. “We’re trying to reach every segment of our population on campus with education and prevention resources. I think everybody needs to do as much as Dana Hills high school.”

In the US, call or text SAMHSA’s National Helpline iat 988. In the UK, Action on Addiction is available on 0300 330 0659. In Australia, the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline is at 1800 250 015; families and friends can seek help at Family Drug Support Australia at 1300 368 186