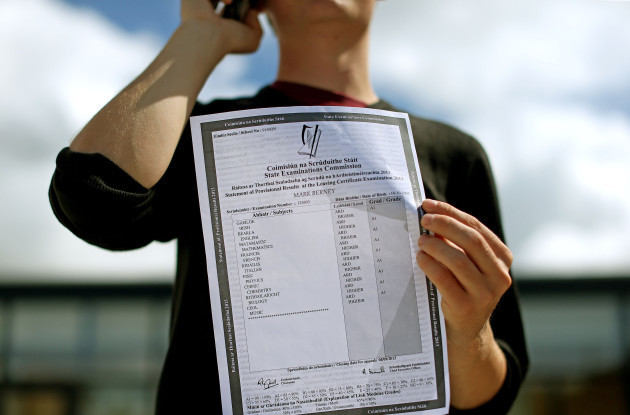

This comes as a record number of students did not sit an Irish exam as part of their Leaving Cert this year, as reported by The Irish Times.

Of the 60,839 students who sat their Leaving Cert exams this year, 13,695 – or 22.5% – were not registered to sit an Irish exam.

This is compared to 2023, when 12,578 students out of the 61,736 who sat the Leaving Cert did not sit an Irish exam.

While Irish is a mandatory subject at second level, students are not required to sit the Leaving Cert exams for the language. Many students who opt out of the exam have received an exemption from studying the language.

According to the Department of Education, exemptions are granted on the grounds of a student having been educated outside of Ireland for a certain period of time, having significant literacy difficulty or having other additional needs.

The decision to exempt a student is made by the principal of the school following discussion with a student’s parents or guardians, the class teacher, special education teachers and the student themselves.

The Department of Education told The Journal that statistics on the number of students holding exemptions from the study of Irish for the 2023/24 school year are not yet available. The Department said that last year, a total of 8,474 sixth year students held an exemption from the study of Irish granted at school level. This means 4,104 Leaving Cert students not holding a school level exemption from the study of Irish did not sit an Irish exam.

“This compares to 4,388 students not sitting a Mathematics examination and 4,463 students not sitting an English examination,” the Department said.

Julian de Spáinn, General Secretary of Conradh na Gaeilge, told The Journal that it is “very concerned” about Irish in education, adding that the language risks becoming an optional subject if more students continue to opt out of learning it.

“It’s not a surprise for us. The numbers have been increasing over the last number of years,” he said.

De Spáinn said Conradh na Gaeilge - a cultural and social organisation which promotes the Irish language – has been calling for the system to be based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). The CEFR is an international standard for describing language ability. It organises language proficiency on a six-point scale, from A1 for beginners to C2 for those who have mastered a language.

De Spáinn said the system focuses on a skills-based approach. “For example, a student who has a learning disability with writing the language, instead of excluding them from learning Irish, surely we should be able to include them and have a Leaving Cert for them that would be based on oral Irish only.

“For a student who comes late into the system, instead of excluding them from learning Irish, which is not a very good thing for integration, why couldn’t they do the beginner level for Leaving Cert and get their points based on that, recognising that they’re only in the system for a small number of years, therefore they wouldn’t be on the same level as other students who have gone through the system.”

The 2020 Programme for Government states that the government will provide “a comprehensive policy for the Irish language from pre-primary education to teacher education for all schools”. But de Spáinn says this commitment has not yet been met.

“We’re not in a good place in the schooling system, whereas outside of school, obviously, there’s huge interest in language. I think that’s growing more and more,” he said.

“Inside the education system at the moment, there’s a huge amount of problems there. We need an overall policy from preschool the whole way to third level to solve and to change the way that we look at Irish in the education system and allow people access Irish in the education system.”

According to de Spáinn, Wales, which is implementing the CEFR system, should be seen as an “exemplar” for Ireland when it comes to teaching and learning the native language.

It is compulsory to learn Welsh in school up until the age of 16 and students must sit the GCSE exam either as a first language or second language. The country has set a goal that at least 40% of all learners will receive Welsh-medium education by 2050.

Ireland does not have such a goal, de Spáinn said. “There’s a lack of ambition when it comes to Irish in the education system from governments in previous years, not just the current government.”

Speaking on Newstalk Breakfast this morning, Tánaiste Micheál Martin denied exemptions for Irish were a “scam” and said he had witnessed difficulty in getting exemptions, particularly among students who may not have been born in Ireland.

“We have a lot of people coming from different countries working in Ireland – French, Italian, Brazilian, Indian and so on – whose kids may not be in a position to do mandatory Irish. I think we need to analyse it a bit more,” he said.

“There are more people speaking the Irish language today than there was at the birth of the nation. The development of Gaelscoileanna over the last 30 years means we have a far greater proportion of people who are fluent in the Irish language and I know this myself [from] talking to them.

“I’d be more positive and optimistic about the Irish language.”

De Spáinn said that even with the current flawed system, he would encourage people to continue to learn Irish.

The Irish Language Network for the Public Sector has set a target that 20% of recruits to public bodies will be competent in Irish by the end of 2030.

“There’s more and more job opportunities that are arising for people who have Irish, even at the basic level,” he said.

“They’re looking for lawyers and lawyer linguists in Europe, they’re looking for accountants with Irish. There’s more and more opportunities going to be there for people who have Irish, so it’s good to keep the Irish going.”

Leaving Cert Irish: Record Numbers Opt Out

Nearly 61,000 students got their Leaving Cert results on Friday; however, nearly one-quarter of them did not sit Irish.

The 13,695 students who did not take Irish amounts to 23% of all Leaving Cert students – up from 15% just six years ago.

The majority of those who did not sit the exam have received exemptions on the basis of learning difficulties or having been educated outside of Ireland for a period.

On Newstalk Breakfast, presenter Ciara Kelly said the exemption system is being abused.

“We have a record number of people sitting the Leaving Cert, but almost one-in-four are not sitting Irish,” she said.

“This is because of exemptions largely but bear in mind, when you drill into those exemptions, these same people who have this specific language deficiency - some kind of learning disability around language - they're sitting Spanish and they’re sitting French and German and Italian and these kinds of modern languages, they’re just not sitting Irish.”

She said there is no such thing as a learning disability that prevents people from doing Irish but allows them to take other languages.

“People are using exemptions to get out of doing Irish,” she said. “We have Irish as a mandatory subject in school, but almost a quarter of kids not taking it and that is despite [the rise in] Gaelscoileanna now.

“So, more and more people are actually speaking Irish and even doing their Leaving Cert through Irish than ever before but despite that, we have the largest number of exemptions.”

“So, there's something going on and I think the exemption thing is being abused.

“There is not one-in-four people who have a learning disability, there simply isn't, so the exemption thing is being abused.”

The Rise of Irish Exemptions

While almost 61,000 students received their Leaving Cert results on Friday, 13,695 or 23 per cent of candidates were not registered for Irish exams.

The proportion of students not sitting Irish exams has been climbing steadily since 2018 when the equivalent figure was at 15 per cent. Irish is mandatory at second level, however, there is no obligation to sit the Leaving Cert exam.

The bulk of candidates who do not sit the exam are typically students who have received exemptions to study Irish on the basis of learning difficulties or having been educated for a time outside the State. In addition, there are students who decide to focus on other exams in the hope of maximising their grades or who may be taking on one or two subjects.

Pádraig Ó Duibhir, professor emeritus at DCU and former school principal, said the overall trend in numbers sitting the exam were “going in the wrong way”.

“It is likely that the biggest factor behind the increase is the number of exemptions,” he said. “They have been growing ever since the Department of Education relaxed the rules in 2019 and placed the burden on school principals [on whether to award them].”

Latest official figures show the proportion of students at second level with exemptions has increased from 9.4 per cent in 2019 to 10.5 per cent in 2022.

Prof Ó Duibhir said there was “no such thing as a language learning disability” and called on policymakers to ensure our education system was more inclusive of learners with learning difficulties.

“For example, if a student has dyslexia, the emphasis should be on oral language and students hearing and speaking it, rather than having an emphasis on writing and reading.”

He added: “If left unchecked [rise in numbers with Irish exemptions], people will use this as evidence to show we need to make Irish optional for the Leaving Cert. We only need to look across the water to the UK to see how, if you make the study of languages optional, the numbers will fall off a cliff.”

The Future of Irish in Education

Earlier this year, an Oireachtas committee called on Minister for Education Norma Foley to scrap the system that allows Irish exemptions on the basis that it was “not fit for purpose” and was harming the education system.

The joint committee on the Irish language and Gaeltacht said students experiencing difficulties with Irish should be allocated additional resources and supports before exemptions were considered.

The Dyslexia Association of Ireland, however, said the report demonstrated “a fundamental lack of understanding” about the needs of dyslexic students, and a lack of awareness of the legal requirements to make reasonable adjustments to meet their needs.

Ms Foley has previously defended the system of Irish exemptions and pointed out that a very large majority of Leaving Cert students continued to choose to take the exam and almost half of those did so at higher level. She has pointed to guidelines for schools which highlight the need to support pupils and students with special educational needs in language learning.

It is only after a two-year intervention that an adjudication will be made by school management as to whether a student should receive an exemption. She has also said there were exemptions for languages in other countries, such as the UK, Poland and Italy.

While the debate continues on the best approach to teaching Irish in the education system, one thing is clear: the status of the language in Ireland is a topic that will continue to be debated for years to come.