In the small Midwestern city where I started school, my classmates and I began each day by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and, then, the Lord’s Prayer. The one little Jewish girl in our class was exempt from the second ritual; the rest of us bowed our heads exactly as we were told, eyes shut and hands folded at our waists, and mumbled a particular Protestant version of the prayer. The Catholic kids had to pick up that extra last sentence — the “kingdom, the power and the glory” part — and the few unchurched youngsters just kind of hummed and moved their lips.

When I was in 4th grade, the Supreme Court declared that the U.S. Constitution didn’t allow taxpayer-funded schools to sponsor praying, in a decision noting that it was government-sanctioned prayer that pushed many early English colonists to migrate to America.

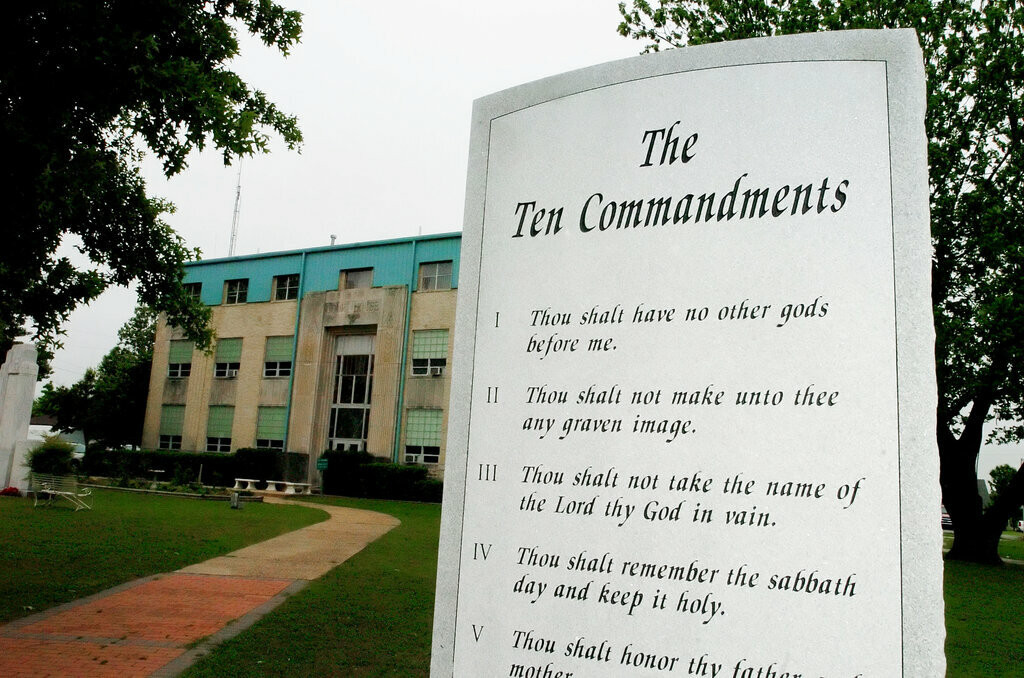

Now, more than six decades later, in a society far more diverse than what I knew as a kid, some politicians are eager to ignore that view of the Constitution. A new law was supposed to take effect this month in Louisiana that requires every classroom receiving public funds in the state — from kindergarten through college — to post the Ten Commandments on a poster at least 11 inches by 14 inches. Since the Bible actually has three versions of the so-called Decalogue, and many translations, the legislature had to specify the words that it considers sacred – so the law adopts the Ten Commandments from the version that was authorized in 1604 by King James I of England.

That archaic language is kind of cool because in the eighth of the King James version’s 10 “thou shalt nots,” a neighbor’s wife is categorized alongside his manservant, his maidservant and his cattle — all those being possessions, you know, that you’re not supposed to covet. Just imagine the thoughtful conversations that commandment might provoke in a Louisiana classroom!

Examining the Ten Commandments Law's Implications

Perhaps that notion of owning a spouse and a servant might yield some discussion of the historical denigration of women in society or the legacy of slavery in America. Probably not; talking about slavery can get a teacher in trouble in a lot of Republican-led states -- Louisiana unlikely to be an exception.

All that is just conjecture, though, because a court has ruled that the law can’t yet take effect, because of a lawsuit claiming that the law is – imagine this! – unconstitutional.

What’s made clear by a law that requires an 18th-century communication medium, using 17th-century English and embracing medieval notions of patriarchal property rights, is that Louisiana’s Ten Commandments law is like a whole lot of religious talk nowadays – that is, it’s a political statement, not an educational one. It’s aimed at reminding evangelical Christians that they need to look nowhere but to the MAGA movement for guidance, because that’s where the push is coming from for this kind of legislation. And in that, it is entirely performative, like so much in politics these days.

The Moral Education Debate

What it is not is any good for the kids.

Mind you, it’s entirely appropriate for legislators, who broadly prescribe what will be taught in state-funded schools, to be concerned about the moral education of children.

But Louisiana’s politicians have actually sidestepped that issue. It’s impossible to believe that they believe this particular law is the right way to teach kids not to kill, steal, lie, commit adultery or want to own that lady next door. They know that it is unconstitutional. The current Supreme Court’s conservative majority calls itself “originalist” – meaning that the Constitution must be interpreted as it was understood at the time of its adoption. The Ten Commandments were nowhere in the founders’ deliberations, and in fact, the Constitution nowhere mentions either God or the Bible. Even a Trump-infused Supreme Court can’t affirm so blatant an affront to the rule of law as that Louisiana statute.

The Historical Context and the Founders' Vision

Beyond the view of America’s founders that government shouldn’t hold sway over what people could believe was a practical notion: There was so much religious diversity in the 13 original colonies that the promise of full religious freedom was key to assuring that the Constitution would be ratified and the union survive. Even a Trump-infused Supreme Court won’t so blithely banish precedent and affirm so blatant an affront to the rule of law as the Louisiana statute presents.

Here’s what’s good to remind those who would force their particular religious beliefs on schoolchildren: Indoctrination with one set of views ill prepares citizens in so varied a world as today’s for the interactions with others that are necessary to forge a peaceful co-existence. Children need to grow up with a morality that respects, as much as possible, all of the world’s great teachings.

The Violation of the First Amendment and the First Commandment

But instead of advancing the sort of preparation for the world that might give young people breadth and understanding, we’re watching politicians pilfer a text that billions of people consider sacred and use it as a performance prop. That could strike one as a violation of not just the First Amendment, but also the First Commandment – you know, that part about not taking the Lord’s name in vain. Clearly, the lessons of those verses have been lost on some of those who claim to be its righteous advocates.

Rex Smith, the co-host of The Media Project on WAMC, is the former editor of the Times Union of Albany and The Record in Troy. His weekly digital report, The Upstate American, is published by Substack.