It’s an achievement to stretch a single idea as thinly as this retrospective of Michael Craig-Martin does. You start by laughing with him, in his clever classics of 1970s conceptual art. You end by laughing at him and the Royal Academy for thinking that his later, gapingly empty paintings and videos can really fill up the main galleries at Burlington House with their re-workings of the same exhausted theme.

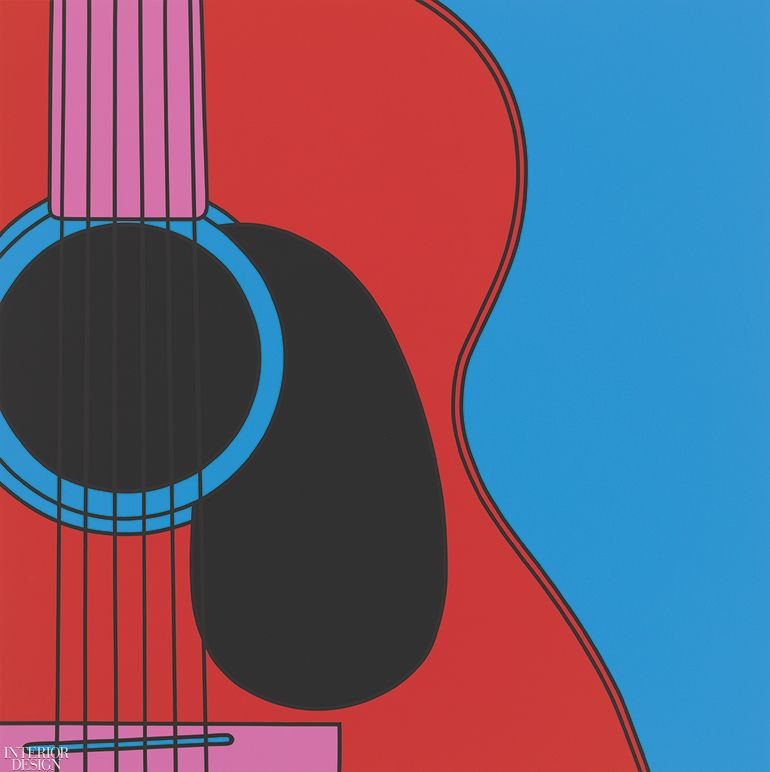

That theme is objects. Craig-Martin has spent decades drawing and painting things, the more modern and ordinary the better: safety pins, forks, iPhones, wheelie suitcases. He depicts them with a designer’s precise perspective in a cool, clinical style with clear lines and neon-bright colours.

But why? There’s no sense of compulsion in these big yet pointlessly crowded pictures of stuff. Great modern artists of the object like Giorgio Morandi, Marcel Duchamp or Giorgio de Chirico convey a mystery and wonder in their often obsessive studies. Craig-Martin seems to do it because artists like this did it. His 2012 screenprint series, Art and Design, pays homage to modern masterpieces of object-art including Duchamp’s Bottle Rack and the pipe from René Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images. In each case he turns the confounding original into one of his insta-drawings.

The reason, surely, that Craig-Martin’s pictures have a textbook quality is that he spent so much of his career teaching. He taught in art schools from 1966 onwards, most famously at Goldsmiths in the 1980s when his pupils included Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst and Gary Hume.

The first work in this exhibition shows you what must have made him such an inspiring teacher, setting Hirst’s imagination, especially, alight. It is his most engaging work, An Oak Tree, created in 1973. A glass of water rests on a glass shelf against the white wall. The title, An Oak Tree, is printed on the wall. And a text explains how and in what sense this glass of water is actually an oak tree.

It is crucial to this work that there’s absolutely no visual similarity between the glass of water and an oak tree. You can’t “see” an oak tree in the way it sits on the shelf. Whatever makes it an oak tree is not visible. In the text beside it, Craig-Martin answers questions from an imaginary interviewer. The glass is not a symbol of a tree. Nor has he merely called it an oak tree: “What I’ve done is change a glass of water into a full-grown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water.”

This conceptual artwork is a philosophical conundrum, reversing Magritte’s Treason of Images in which “This is not a pipe” appears under the picture of a pipe. But the philosophy this artwork is playing with is not modern. It’s medieval.

Craig-Martin, who was born in Dublin in 1941 and educated in Catholic schools in the US, parodies the Church’s most influential philosopher Thomas Aquinas. The 13th-century thinker ended the biggest theological debate of his time – how the body of Christ can be actually present in the bread and wine of the Eucharist – by applying Aristotle’s philosophy to explain that while the “accidents” – the superficial appearances – of bread and wine are unchanged, the “essence” is transformed into the holy presence of Christ’s body.

An Oak Tree is Aquinas meets Monty Python. Transubstantiation as farce. It claims a godlike power for the artist. Like a god, the artist can transubstantiate a glass of water into a tree. Or like Jesus who turned water into wine.

This must have electrified the young Hirst. His teacher helped him to see that conceptual art and the Duchampian readymade were a kind of magic that let artists turn glasses of water into trees, or dead animals into piles of cash.

If Craig-Martin’s early art gets its energy from the mixed feelings of a young man struggling with Catholicism, the banality of his later paintings seems to reflect an all-too-secular eye, free from guilt or superstition.

From the 17th-century painter Zurbarán seeing the Virgin Mary in (yes) a cup of water to the lifelong Catholic Warhol finding the sacred in a can of soup, many great still-life artists have been religious. They see the soul in stuff. Please don’t think I am proselytising for religious art. But if things are just things, how interesting can they be? I can’t share Craig-Martin’s endless fascination with electric torches, cork screws and credit cards. Then again it doesn’t seem like fascination. It’s more like the dry irony of someone who’s forgotten what he’s being ironic about.

Obviously the Royal Academy is in on the joke that eludes me because they confine An Oak Tree and his other engaging conceptual works from the 1970s to one room, before moving on to the supposedly bigger story of how he became a painter of snazzy, 21st-century still lifes. With their hard, cool colours in acrylic on aluminium these pictures seem to declare they are made for the “grey matter”, as Duchamp called the brain.

But there’s not enough brain food in them for a cat.

The Artist and the Object

‘Of all the things I’ve drawn,’ Michael Craig-Martin reflects, ‘to me chairs are one of the most interesting.’ We are sitting in his light-filled apartment above London, the towers of the City rising around us, and we are discussing a profound question, namely, what makes an object a certain type of thing? Or to put it another way, what makes a chair a chair?

Craig-Martin’s career has been characterised by what he calls ‘my object obsession’. There will be chairs on view in the grand retrospective of his work which is about to open at the Royal Academy, but by no means only chairs. The galleries will be filled by a cavalcade of mundane bits and pieces, among them safety pins, filing cabinets, forks, smartphones, pliers, light bulbs and buckets. All of these are drawn with a thick, clear black line and painted in vivid, joyous and completely non-naturalistic colours.

‘I changed a glass of water into a full-grown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water’

Craig-Martin could be categorised as a highly individual variety of still life artist. And still life is a genre that leads artists to muse on the nature of things, from Zurbaran in the 17th century to Picasso and Braque in their cubist phase. This brings us back to the chair-ness of chairs.

‘Chairs,’ he goes on, ‘have been made out of every material you can think of – metal, wood, plastic, rubber, cloth, cork. They’ve come in an incredible number of forms and designs. And yet a chair is a chair and every one of them is rightly called a chair.’

I faintly recall encountering this conundrum many years ago as a first year philosophy undergraduate, writing an essay on ‘the problem of universals’. This involved puzzles such as ‘what makes a chair identifiable as a chair even though it looks different from all the other chairs?’. ‘I love all that!’ says Craig-Martin. ‘My approach to art is philosophical in a sense.’ Although, he quickly qualifies: ‘It’s not serious philosophy.’

His metaphysical turn of mind originated in a ‘very classical Catholic education’. This took place in America because although Craig-Martin was born in Dublin in 1941, his father worked for the World Bank and was posted to Washington. Consequently, at school he learned such subjects as logic and rhetoric which were prominent on the medieval syllabus. He finished by studying art at Yale, just when American artists were developing minimalism, performance and immaterial art forms consisting primarily of ideas.

Eventually, after this complex education, Craig-Martin produced a masterpiece, influenced in equal measure by St Thomas Aquinas and Marcel Duchamp. He exhibited this in London in 1974, having moved to Britain, appropriately enough, because of a problem of definition. He was looking for a teaching job in the US, but his work at the time – ‘constructions made out of plywood and cloth’ – wasn’t deemed to be sculpture. ‘So I couldn’t get a job in a sculpture department, but they clearly weren’t paintings, so I couldn’t get a job in a painting department either.’ Nonetheless Craig-Martin was offered a post in Britain (and he’s still here getting on for 60 years later).

An Oak Tree

In 1974, he went to see Alex Gregory-Hood, proprietor of the Rowan Gallery on Bruton Place. He said: ‘Alex, I want to have an exhibition where I have a glass of water on a shelf in the gallery, and I don’t want anything else there.’ Gregory-Hood said OK (this was the early 1970s, a mildly revolutionary era even in England).

Craig-Martin found a photograph taken at the opening which he showed me, noting: ‘There weren’t a hundred people there; there weren’t 50. There were 12.’ All of those attending are crowded around a desk on one side where it was possible to get a drink. They have all turned their backs on the sole exhibit, which was placed high on the opposite wall. There, precisely in the centre of a shelf placed too high for anyone to reach, was indeed a tiny glass of water.

The title of Craig-Martin’s work was ‘An Oak Tree’, (see below). On the desk was a printed text containing a dialogue between the artist and an understandably sceptical viewer. In this, with unruffled reasonableness, Craig-Martin made an astonishing claim: ‘What I’ve done is change a glass of water into a full-grown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water.’

Naturally, the questioner wants to know what he means by ‘the accidents’, so Craig-Martin explains in terms that would have been comprehensible to Aristotle and Aquinas: ‘The colour, feel, weight, size…’ So, the interrogator goes on, you mean it’s a symbol of a tree? ‘No,’ replies the artist, ‘I’ve changed the physical substance of the glass of water into that of an oak tree.’

Even if the vernissage was not well attended, Craig-Martin continues, ‘An Oak Tree’ soon ‘took on its own life. Years ago it somehow ended up with its own Wikipedia page’. It’s been shown all over the world. In 1976, en route to an exhibition in Australia, it was seized by customs on the grounds that the importation of plants was forbidden.

Of course, that’s funny – and so, intentionally, is the dialogue. But it’s a deeply serious joke. The distinction between substance and accidents has been debated down the centuries. It underpins the doctrine of transubstantiation (according to which the substance of the bread and wine of the eucharist are changed into the body and blood of Christ, while their outward characteristics are unaltered).

Craig-Martin’s point was not religious, however. He was intrigued by how a collection of materials – paints, canvas, wood, stone, whatever it is – is transformed into something potentially fascinating and immensely valuable: a work of art. According to art-world dogma, this happens at the moment a painter declares a picture finished. For Craig-Martin himself ‘An Oak Tree’ posed a different sort of problem. Where to go from there? It was the conceptual art piece to end all conceptual art pieces. ‘I either had to say, “For the rest of my life I will be the person who did that” or start again doing something different. So essentially, I decided to go back to basics. For me basics meant drawing.’

At this point he formulated his manner of delineating his chosen repertoire of things and continued through the late 1970s making wall-drawings, sculptures and other mainly monochromatic works.

The Artist and the Colour

Then in the mid-1990s came an almost literal light bulb moment. Craig-Martin added singing colour to his pictures. His palette is anything but naturalistic. An empty sardine tin (a favourite motif) might be cerise and sky blue, a pencil sharpener lime green. This is more a philosophical idea of colour than realism, but at the same time it’s extremely jolly.

‘As soon as I introduced colour, I realised that even for myself it was an emotional release. I could see immediately that I was getting a different kind of response. People were excited to see the works. They laughed.’ After all, art is not only an idea, it has other ingredients such as pleasure.

Craig-Martin points out that he did the first of these ebulliently multi-hued pictures in 1995-6, when he was around 55. ‘I’ve kind of given myself a whole career in a condensed way because I started late. I’m very happy with everything I did before, but I do see it as preliminary.’ As a result, he has been extremely busy for the past 30 years.

On his 60th birthday, he remembers thinking: ‘I don’t feel in any significant way different to the way I did when I was 50. While I’ve got the energy I’d better work my arse off.’ He renewed this vow on his 70th birthday. The day before we met, Craig-Martin turned 83, and evidently he’s still not letting up.

‘I’ve had an incredible year,’ he confides, working on something new: an immersive installation with a sound track, which will take up a whole room of Burlington House. ‘[This] lasts about half an hour, it’s entirely animated, a video projection, four metres high, on all four walls and it has a soundscape with it.’

In a way this will be a retrospective in itself since it contains almost every drawing he’s done since the 1970s – but in a brand-new medium. It may seem a long way from a glass of water on a shelf, but it still raises that intriguing, insoluble question: what is a work of art?