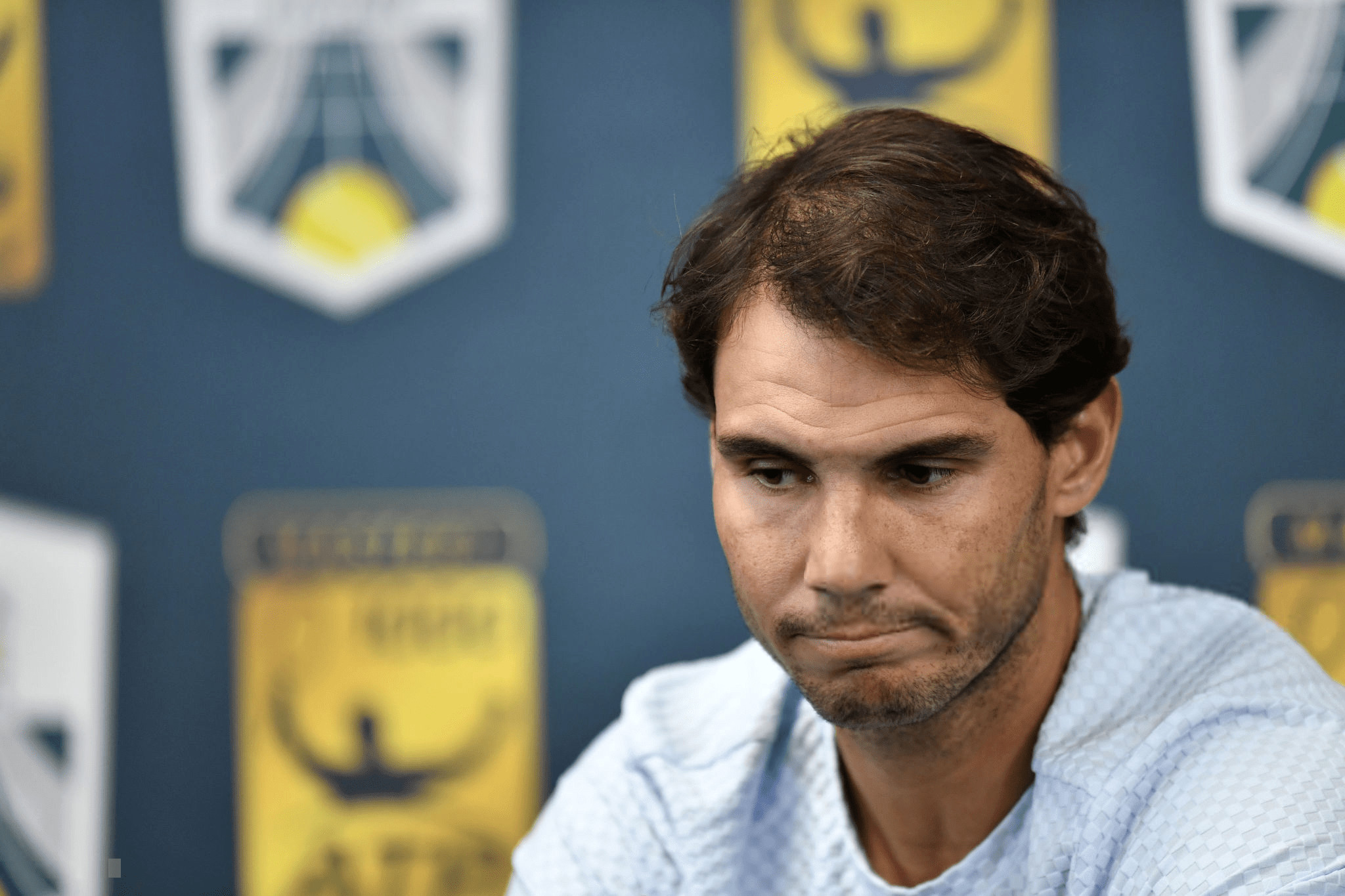

Tennis legend Rafael Nadal has announced his upcoming retirement from the sport after a glittering career in which he amassed 22 grand slam titles. Widely regarded as one of the greatest tennis players of all time, Nadal’s final tournament will be with Spain at the Davis Cup finals in November.

The 38-year-old last played at the Paris Olympics but continuing injury struggles, which have hampered him throughout his career, have severely limited his time on the court over the past two seasons. “Hello everyone, I’m here to let you know that I am retiring from professional tennis,” Nadal said in a video posted on social media. “The reality is that is has been some difficult years, these last two especially. I don’t think I have been able to play without limitations.

“It is obviously a difficult decision, one that has taken me some time to make. But in this life, everything has a beginning and an end. And I think it’s the appropriate time to put an end to a career that has been long and much more successful than I could have ever imagined.”

Nadal, who was forced the skip last month’s Laver Cup over fitness concerns, announced last year that 2024 would likely be his last season on the tour. His 22 grand slam titles are the second-most in history of men’s tennis behind only Novak Djokovic, his great long-time rival, as are his 36 Masters 1000 titles. Nadal has also won singles and doubles gold for Spain at the Olympics and led his country to five Davis Cup titles.

Dubbed the “King of Clay” due to his remarkable dominance on the surface, Nadal won 14 of his grand slams at the French Open and lost just four of his 116 matches in Paris. He also won the US Open four times and the Australian Open and Wimbledon twice, while his victory over Roger Federer in the 2008 Wimbledon final is widely considered the greatest tennis match of all time.

“I am very excited that my last tournament will be the final of the Davis Cup and representing my country,” Nadal added. “I think I’ve come full circle since one of my first great joys as a professional tennis player was the Davis Cup final in Seville in 2004. I feel super, super lucky for all the things I’ve been able to experience.

“I want to thank the entire tennis industry. All the people involved in this sport, my long-time colleagues, especially my great rivals. I have spent many, many hours with them and I have lived many moments that I will remember for the rest of my life.

“Talking about my team is a little bit more difficult for me because in the end, my team has been a very important part of my life. They are not co-workers, they are friends. They have been by my side at all the times I have really needed them. Very bad moments, very good moments.”

Nadal had suggested throughout the season that he could continue playing into next year if his body allowed him to be competitive. After missing the majority of 2023 due to a hip injury, Nadal returned to competitive tennis at the Brisbane Open in January but was forced to miss the Australian Open with a thigh injury. He has played in only six tournaments since then, most recently the Paris Olympics where he lost to Djokovic in the second round of the men’s singles.

“I leave with the absolute peace of mind of having given my best, of having made an effort in every way,” he said.

Federer, whose rivalry with Nadal is arguably the greatest in tennis history, said it was an “honor” to play against the Spaniard. The pair shared a tearful moment that went viral during Federer’s own retirement ceremony in 2022. “What a career, Rafa!” Federer wrote on Instagram. “I always hoped this day would never come. Thank you for the unforgettable memories and all your incredible achievements in the game we love. It’s been an absolute honor!”

The Ultimate Clay-Court Test

Casper Ruud is describing what it’s like facing Rafael Nadal on Court Philippe-Chatrier at Roland Garros: the court where Nadal has won 14 French Open titles. Ruud was the beaten finalist for the most recent of those triumphs, in 2022. When asked to relive the experience of facing Nadal there, his eyes widen and he lets out a small laugh.

This was a pretty typical reaction of the dozen-or-so players The Athletic spoke to in an attempt to understand exactly what it’s like playing Nadal on clay — a surface on which he has a 90.9 per cent winning record over a career that has spanned more than two decades. He has won 484 ATP matches on clay, losing just 51. At Roland Garros, that figure is a ludicrous 96.6 per cent. Played 116, won 112, lost four.

The players we heard from, including Novak Djokovic, almost unanimously described playing Nadal on clay as “the toughest test in tennis”. Others, like Ruud, went as far as saying it was the toughest test in any sport. “He is the ultimate clay-court player,” says Gael Monfils, the one-time world No 6, who has been beaten by Nadal in all six of their meetings on the surface.

Some players don’t even think it’s real. “It’s a bit like playing against someone on a PlayStation because every ball comes back,” is the view of Karen Khachanov, a two-time French Open quarter-finalist.

Ruud’s words call to mind Andy Roddick’s famous “first your legs, then your soul” description of Novak Djokovic, so what exactly makes playing Nadal specifically so terrifying?

From the size of the Chatrier court and the feeling that it’s impossible to get the ball past him, to the heaviness of his ball, to the mental torture he is able to exert, those who have faced him explain exactly what it’s like playing Rafael Nadal on clay.

Playing Nadal on Chatrier

Let’s start with the ultimate, ultimate test — playing Nadal on Chatrier. Since winning his first French Open in 2005 as a 19-year-old, this has become his court. He knows its dimensions perfectly; he knows how the ball will bounce in any spot; he knows how to inflict the maximum amount of damage on his opponents. Sometimes a player and a court become so intertwined that it feels as though the venue were made for them. Roger Federer and Centre Court, Serena Williams and Arthur Ashe, Djokovic and the Rod Laver Arena.

First up, the man who has inflicted two-thirds of his defeats on the court and who has played him there more (10 times) than anyone else — Djokovic. “The court is bigger,” he says. “There is more space, which affects visually the play a lot and the feeling of the player on the court. He likes to stand quite far back to return. Sometimes when he’s really in the zone and in the groove, not making many errors, you feel like he’s impenetrable. He’s like a wall.

“It’s really a paramount challenge to play him in Roland Garros. He’s an incredible athlete. The tenacity and intensity he brings on the court, particularly there, is something that was very rarely seen I think in the history of this sport.”

“It’s like Novak said, winners don’t come easy against him on Chatrier,” adds Ruud, who is a clay-court specialist and has been ranked as high as No 2, but was thumped in straight sets in that Roland Garros final two years ago. “He reads the game so well, as well as him being one of the best movers of all time.”

To reach that final, Nadal beat Alexander Zverev in the semi-final. In a very strange match with lots of breaks, Zverev had to retire with an unfortunate ankle injury in the second set while trailing 6-7, 6-6. He had somehow failed to win the first set, despite holding four consecutive set points, and the way he talks about it now underlines how much the match has stayed with him. The way he describes Nadal conjures up the image of trying to escape from the Terminator in the classic Arnold Schwarzenegger film.

“He becomes different,” says Zverev, who has lost five of his seven matches against Nadal on clay. “His ball all of a sudden becomes a few kilometres an hour faster. His footwork and foot speed become a lot faster.

“It’s more difficult to hit a winner, especially on Philippe Chatrier, which is a massive court, so he has a lot more space. It is very difficult. It’s probably the biggest challenge in tennis playing Nadal on that court.

“You have a feeling that you just can’t put him away. I think the first set that I played against him (in that 2022 semi-final) basically describes it to perfection. I mean, I won that set I don’t know how many times against any other player and I still somehow managed to lose it in the tie-break.

“I was up 6-2 in the tie-break. He aced me I think for the first time in the entire match. Then he hit one of the most ridiculous passing shots I’ve ever seen in my entire life.

“Somehow you feel like you’re winning, but then somehow you end up not. It’s just something you only feel against him on that specific court.”

Zverev did finally get his Roland Garros win against Nadal, beating him on Court Philippe-Chatrier in the first round of the 2024 tournament — Nadal’s last French Open.

The Nadal Backhand: A Weapon of Destruction

Sebastian Korda, America’s world No 28, won just four games when he faced Nadal on Chatrier four years ago, losing 6-1, 6-1, 6-2 in a fourth-round shellacking. He feels Nadal’s comfort and experience on the court adds to the feeling for opponents that no situation could unsettle him there.

“He’s as comfortable as someone can be on a tennis court and once someone gets comfortable on a court, it becomes extremely difficult to play them,” Korda says. “He’s been through pretty much every situation on that court so plays as free as anyone can on a court. You feel like you can’t get the ball past him.”

Khachanov, the big-hitting Russian world No 17, was thumped by Nadal 6-3, 6-2 in their only meeting on clay — in Monte Carlo six years ago. “It was a bit like playing against someone on a PlayStation because every ball comes back,” he says. “Sometimes you have trouble winning one point. And you can feel like you do everything right and you don’t win the point.

“You serve well and open the angle, the ball comes back. That’s why he’s unique and the best ever to play on that surface.”

The feeling that whatever you do isn’t enough ties into Ruud’s description that “first he takes your legs and then your mind”. There’s worrying about what to do when you’re hitting the ball. There’s the growing sense that whatever you do, it won’t be enough. Then there’s the fact that for every ball you hit, Nadal’s ball is about to come for you.

His ball on clay is known to be so full of spin that players struggle to comprehend it until they experience it first-hand. This can be quantified to some extent by looking at the extremely high revolutions per minute on Nadal’s shots, especially the forehand, but even that doesn’t fully do it justice, his opponents say.

“His ball? It’s… heavy,” says Ruud, who was also the French Open runner-up in 2023. “And I think if you haven’t played tennis yourself it’s maybe hard to know what heavy means. I guess it’s the spin and rotation of his ball. The more RPMs he has on his ball, the quicker it will bounce up towards you. And when the ball bounces up at you, the more RPMs it has, the heavier it comes up at you compared to a ball that’s coming at you really flat.

“He has mastered that more than anyone else.”

World No 55 Miomir Kecmanovic lost to Nadal in straight sets in Madrid a couple of years ago and says: “His ball was different. Different in the way you know it’s Rafa behind the ball. Sometimes even if it’s not as good you still feel the pressure because you know it’s him. It’s completely different when you play him.”

Khachanov says it’s the variety of Nadal’s ball when playing him on clay that really struck him. “It’s always different,” Khachanov says. “He finds different angles, different trajectories, he always pushes you back when he opens the court. He has so much variety and the ball speed. So whenever he wants to be aggressive, he goes aggressive, and if he wants to be more defensive, he can take a step back. It’s like chess tennis — with the pieces, the shots he has in his arsenal. He is always trying to make you have trouble.”

Nadal's Mental Game: A Force of Nature

Such a kind person off the court, there’s no doubt that Nadal has a sadistic streak on it. He seeks out opponents’ weaknesses and exploits them mercilessly — especially on clay, where the high bounces suit the violent topspin he puts on the ball. Roger Federer could be forgiven for still having nightmares about those French Open finals when Nadal would loop topspin forehands to force him to hit one-handed backhands from shoulder height again and again. The punishment was so severe that Federer eventually remodelled the entire shot.

Grigor Dimitrov, the world No 10 and three-time Grand Slam semi-finalist, is another gifted shotmaker with a single-handed backhand. He has faced Nadal six times on clay and lost all six meetings — winning just one set in the process. He recalls Nadal making his life as awkward as possible. “It was no fun. No fun at all,” Dimitrov says. “I played him at his absolute peak on clay and how can I explain? It’s just very uncomfortable. It’s very difficult for a one-hander to play him on any surface, but clay especially. The direction on the ball is very different. You have to move a bit extra. You can’t make any cheap mistakes. Overall there’s so little margin for error and then if you can’t put him in an uncomfortable position, there’s not a lot you can do.”

One of Nadal’s characteristics is that he never takes things for granted. No matter the opponent or the event, he will always show every match the utmost respect. Part of that is properly researching his opponents and knowing how to exploit any holes in their game. That was the impression that Zizou Bergs, the world No 101, had when he was beaten by Nadal in Rome earlier in 2024. “He was hitting such a high ball with lots of spin,” Bergs says. “Playing my weaknesses. You can tell his team did their homework on me, on what I don’t like. The intensity he can give sometimes with his forehand and backhand, it’s brutal.”

The feeling of being put under relentless pressure is draining and eventually, it becomes overwhelming. “It’s difficult physically, tactically to handle his speed, his angle, the way he puts you under pressure,” says Monfils. Corentin Moutet, the world No 79, played Nadal at the French Open two years ago. He shakes his head as he remembers trying to reconcile the fact he felt he gave a good account of himself but still lost in straight sets. “I played well that day,” he says. “And left the court thinking I’ve played a really good level here but it’s still not enough.”

One of the biggest challenges about playing Nadal on clay is the mental aspect. Trying to go into the match not fearing what is about to come. And playing Nadal on Chatrier can do strange things to people. Ahead of their first-round match at Roland Garros five years ago, the German player Yannick Hanfmann was so frazzled that after the customary photo at the net, he stuck his hand out to Nadal as if it was the end of the match. A slightly bemused Nadal didn’t leave him hanging and politely shook it. “That was weird. I don’t know what I was doing, to be honest. I was a bit out of it there,” Hanfmann said afterwards. “I saw him shaking this kid’s hand and the ref’s hand and I then stuck out my hand. I don’t know why.”

This is an extreme example, but there’s no denying that players struggle not to be overawed by the prospect of facing Nadal on clay.

“I think the fear shouldn’t be a factor,” Dimitrov says. “But the way certain players are, and him on clay, with a 97 per cent winning percentage, it’s already difficult enough. But I think the mindset is really important. You have to really believe that you can play well enough to have a chance.”

The Idolatry Factor

As time has gone on, there’s also the challenge that many players who face Nadal grew up idolising him. How do you switch off the part of your brain that is so full of admiration for him and listen only to the one that tells you you need to go and, metaphorically speaking, kick the living daylights out of him?

“It’s about being out there, having tonnes of respect for Rafael Nadal, but also seeing him as your opponent you want to beat and not just want to play,” says Bergs, who led Nadal by a set in Rome before succumbing in three. “Sometimes you lose because you don’t really believe.”

Ruud was one of the players who grew up with Nadal as their childhood hero and then trained at the Spaniard’s academy. There was a feeling that he was overawed by facing Nadal in their final in 2022, which ended with a one-sided 6-3, 6-3, 6-0 scoreline and was happy enough just to be there. “Of course, I wish I could make the match closer and all these things,” he said afterwards. “But at the end of the day, I can hopefully one day tell my grandkids that I played Rafa on Chatrier in the final. I’m probably going to enjoy this moment for a long time.”

Korda had a similar situation when he faced Nadal at Roland Garros in 2020, describing him as his “idol” in the lead-up to the match and having named the family cat after him growing up. Korda admits it was strange playing him in Paris having watched thousands of his matches growing up. “He was my favourite player, so nothing really surprised me,” Korda says. “But it still felt pretty strange seeing him on the other side of the net.”

Even older, more experienced players, confess that at times they had to grapple with the feeling of being honoured to share the Chatrier court with Nadal.

Fabio Fognini, 37 now, was a top-10 player and clay-court specialist. He has played Nadal eight times on clay, winning three of those meetings – including the most recent one, a 6-4, 6-2 hiding in Monte Carlo five years ago. But he admits that during their one meeting at Roland Garros, he was too happy just to be there. Nadal won the match — a third-round contest in 2013 – 7-6, 6-4, 6-4. “I’m happy I was one of the 1,000 players who got to play at the same time as them,” he says. “Being in the second week of a grand slam was a party for me. I played with all three and Andy. I played Rafa at Roland Garros, Roger at Wimbledon, Nole (Djokovic) in Australia, Andy at Wimbledon. They were all incredibly tough.”

Nadal's Legacy: A Clay Court Legend

When the then-37-year-old Nadal battled to compete at one last French Open, it felt as though we had come full circle. With the announcement of his tennis retirement, that is confirmed. Nadal’s biggest opponent since his 14th title two years ago has always been his creaking body, which forced him to miss the 2023 French Open and prevented him from playing any Grand Slam tournaments at all between the 2022 French Open and his final appearance in Paris in 2024.

Nadal finally has some insight into what his opponents have faced all these years. The doubts and fears that consume them. How tough has that been, suddenly having to manage your vulnerability? “Yeah, it’s tough,” he told The Athletic in Rome earlier this year, where he exited the Italian Open early to Hubert Hurkacz. “Because I have to do the things very step by step, trying to make small improvements day by day. I need to try to play at my hundred per cent. It’s not easy because I need to lose a little bit of fear that I have in some shots, for example.”

Beating Nadal at Roland Garros was for so long been the toughest task in tennis, possibly any sport. But in his return from injury in 2024, Nadal’s physical issues meant he was nowhere near as formidable on the surface as he once was when Zverev dispatched him in three close and valedictory sets. Would a fitter, stronger Nadal have won that match? It’s impossible to know. But perhaps it’s fitting that the only person who has properly got the better of Nadal on clay is Rafael Nadal himself.