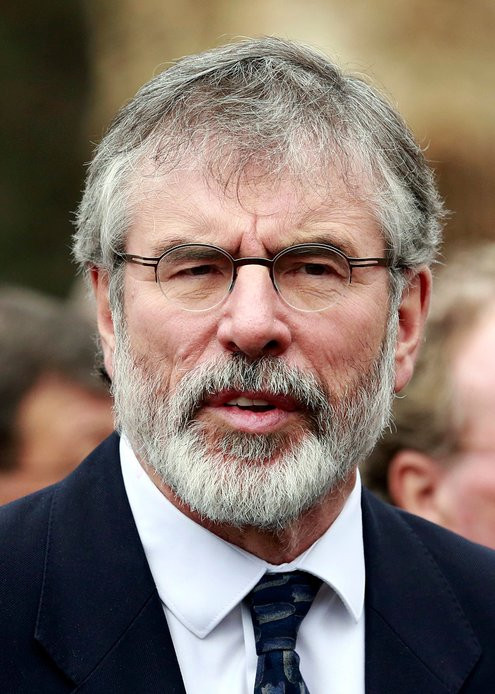

He has sold 5m books about this ancient Greek approach to life – and been feted by sports teams and CEOs. What makes this former PR man so popular?

What is it that made the former PR man turned lay philosopher Ryan Holiday a giant of the bestseller lists? That his writing on stoic philosophy is beloved by everyone from professional athletes, politicians and tech CEOs will have helped. Investor-entrepreneur Tim Ferriss calls stoicism the “ideal operating system”, while entrepreneur-fraudster Elizabeth Holmes constantly cited Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, before her imprisonment. Sports stars from James McGee (Irish tennis pro) to Garrett Gilkey (NFL lineman) can quote from Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way, while celebs from Arnold Schwarzenegger to LL Cool J hat-tip Holiday in interviews.

The ancient philosophy of stoicism centres on four virtues: courage, temperance, justice and wisdom. Marshalling these will give you complete self-control, enabling you to react with equanimity to all outside stimuli, and not whine about stuff (giving us our modern, shorthand definition of stoicism, “uncomplaining”). Material wealth should mean nothing to the stoic, which makes it ironic that some of the richest people on Earth claim to live by stoicism.

The wild popularity of of the philosophy as a way to live is showing no sign of ebbing. Holiday’s various books (of which there are roughly a gazillion) have sold at least 5m copies. The Daily Stoic, Holiday’s brand, which spans a website, newsletter, podcast and Instagram account, has 3 million followers.

It was in 2019 that he hit No 1 in the New York Times bestseller list with his book Stillness Is the Key. This was actually his fourth foray into stoicism as a code to live by: in 2014, he had published The Obstacle Is the Way; then in 2016 Ego Is the Enemy and The Daily Stoic.

When The Obstacle Is the Way came out, “it sold maybe 3,000 copies in its first week”, says Holiday. “It did not exceed anyone’s expectations ... It wasn’t until a year or so later that the sales really started to take off, when it began to make its way through professional sports.” Whole teams – Miami Heat (basketball), Seattle Seahawks (American football) – adopted his books as bibles, “and I found this to be true in every country, in sports that I honestly didn’t even know existed”.

From there he got on to CEO reading lists (Twitter founder Jack Dorsey swears by stoicism, as do venture capitalist Brad Feld and the former chief executive of GoDaddy Blake Irving). Holiday is a bit riled at the criticism, which I don’t put to him, but has been made many times before: that it’s a bit rich, some might say nauseating, to listen to men who have more wealth than they could possibly spend pontificate about self-denial (ice-baths and whatnot); men who hoard material goods and drive gaping inequality bang on about their passion for justice and the Good Life. On his popularity in Silicon Valley, Holiday says, with equanimity, “I’ve always been curious about why that’s a bad thing. What else would you want them to be studying, other than a philosophy built around virtue? You could argue that they’re missing the point, or they’re picking and choosing what they take from it. But there are much darker rabbit holes that people have chosen to go down.”

Unmistakably, the stoics would hate this era – hysteria and volatility everywhere you look. So why have so many people been drawn to the ancient philosophy? “There’s a Flaubert quote,” Holiday says. “He says that between Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, after the gods had ceased to be and Christ had not yet come, man stood alone in the universe. He’s totally wrong, as far as the timing goes, because Jesus and Cicero were roughly the same time period. But this idea of standing alone in the universe: this is the heyday of stoicism.”

Holiday is an unbelievably charming speaker, and it’s something in the contrasts and reversals of expectation; he looks incredibly clean cut and quite serious minded, but he’s happy to take a drive-by at Flaubert, or anyone else (Zeno, founder of the stoics, “a total failure of a merchant”; Chrysippus, the unserious stoic, “literally died of laughter”) and it’s always counterbalanced with a wry self-criticism. If you imagine Tom Cruise in Magnolia – that messianic zeal and self-assurance – but then give the character a sense of humour about himself, you’re approaching Holiday’s appeal. He’s not so much charismatic as just very surprising.

Anyway, back to our era: “When the old understanding of the universe had not given way to the Christian understanding, where was a person to turn for meaning and purpose and structure? A way of living? Stoic philosophy, and indeed all the schools of ancient philosophy, cynicism and Epicureanism, this was a heyday of philosophy as a sort of civic religion.”

OK, fine, who am I to argue? “I think you could argue that we stand alone in the universe again,” he continues. “People are increasingly not religious. People have lost faith in institutions, a lot of old ideas or explanations that people drew structure and comfort from have fallen away. How should a person live? What is the code by which you’re supposed to be a good person? I think the ancient traditions are some of the best answers that man has come up with.”

Which is all completely fine: except don’t people always say that? Aren’t we always saying that the old world has died and the new one is struggling to be born? But this thought only occurs to me after I’ve left the Zoom (Holiday is talking to me from Austin, Texas); in the moment, Ryan Holiday completely deactivated my bullshit-sensors, and for millions of people, he can even do that on the page.

The 37-year-old grew up in Sacramento, California “a sleepy, government town”. He had a straight upbringing – his father was a police detective, his mother a high school principal. I ask if the lack of adversity is a bit of a disappointment to him: in his writing, heroism is framed, defined by the hardscrabble childhood, the stoic who grew up blind, or orphaned, or bitten by beasts or whatever. No, he chastises me (but so charmingly) “because that seems kind-of offensive to the people who did have hard upbringings”. He continues: “I’ve never met anyone whose childhood was easy to them. Even if on the sociological level it was privileged, everyone’s childhood is rough. When I talk about Demosthenes, I relate to it in the sense that I feel like we all know what it means to not have the life you wanted, or not have things go your way. I had two parents that stayed together, that had good jobs, I never really wanted for anything other than maybe some semblance of understanding and support about who I was as a person. We all want Daddy to be proud of us at some level.”

Holiday dropped out of college without graduating, which troubled his parents greatly, not because they had any particular ambition for him, but because they couldn’t imagine life off the school-college-job conveyor belt. “As a maverick or as a rule breaker, I’m pretty tame,” he says. “This is like the most milquetoast rebellion of all time, to become a writer of ancient philosophy.”

In the first instance, though, he dropped out because opportunities were coming at him. He was offered work by the immensely popular author Robert Greene, as well as getting a job as an assistant at a big talent agency in Beverly Hills. All that, when he was only 19. For years, “I was this wunderkind. I was always the youngest specialist person in the room. Now that I have kids, and my hair is starting to go grey, I feel like I’m finally just being treated as a regular person.”

I’ve no way of proving this, but he’s hardly a nepo baby: I’m pretty sure his early success was because he’s so likable. It’s an almost comically unstoical trait.

From Beverly Hills, he found more (very early) success as director of marketing at American Apparel, the buzzy, values-driven brand that turned out to be run by a serial sexual harasser, Dov Charney. Drawing lessons from that time, Holiday remembers, “Dov Charney had to do so many things that were totally insane, right? Like, I’m going to make clothes in America, I’m going to pay workers a fair wage, I’m not going to have branding on them, I’m going to run my own stores. Every one of those things is a bad idea. But it works.

“An entrepreneur, by definition, succeeds by not listening to all the people who told him that it wasn’t going to work. But then you learn this incredibly dangerous lesson, which is, don’t listen to other people when they tell you something is a bad idea. It sows the seeds of your destruction.” This, he says, is a “timeless historical archetype”. I nod. And then, later, realise; that is total rubbish. You don’t learn not to be a sex pest by listening to your executive board; you don’t unlearn it by selling too many T-shirts. There are worlds of human values really not covered by the commercial experience.

It was around the time he was at American Apparel, in his early-to-mid 20s, that Holiday started writing The Obstacle Is the Way, and even though I read the edition that he’s recently revised, it still reads like a young man enamoured of the Great (business)Man theory of history. It’s a compendium of people who don’t listen to experts and, as a result, win big. When the markets are telling you one thing, do the opposite; when doctors tell you you’ll never walk again, just keep on trying to walk.

Rockefeller is the first and probably most jarring example, held up as a role model for overcoming adversity, but really, the only adversity he overcame is that he didn’t start off with all the money in the world, and yet that’s what he ended up with. I can’t help but wonder if, when Marcus Aurelius asked: “Does what happened keep you from acting with justice, generosity, self-control, sanity, prudence, honesty, humility, straightforwardness?”, this is what he had in mind. “I was just trying to highlight a specific personality trait,” Holiday says. In Rockefeller’s case, this was an indefatigable can-do attitude.

Holiday says he has changed a lot since those early days as an author, though his heroes haven’t changed; the revised Obstacles still lauds the former US president Ulysses S Grant for not running away when things exploded (his fables seem to me to be the optimism bias of the histories that get told by people who remain alive; there must have been plenty of other civil war heroes whose stories would have ended better if they had moved away from explosives a bit faster: to take as a wild example, Abraham Lincoln). I’ve missed the point, Holiday says (again, so nicely). “It’s not Grant’s courage under fire, but what he directs that courage to do, which is to keep the union intact and to free the slaves.”

Still, he concedes, his attitudes to stoicism have changed, which is something of a relief to hear given that all his books seem to say completely different things. The first edition of The Obstacle Is the Way is, by Holiday’s own admission, pretty different from the most recent edition. Sometimes it feels that his many books – Stillness Is the Key; Courage Is Calling; Discipline Is Destiny; Lives of the Stoics; Right Here, Right Now: Good Values. Good Character. Good Deeds – do not so much represent a meaningful through-line of the ancient philosophy, but instead pick up quotes and notions so freely, attach them to modern exemplars so randomly, that it’s like putting stoicism into a Magimix until the only building block of thought you have left is the alphabet.

“My initial attraction to stoicism is what it can do for you: how it can make you more resilient, more productive, think clearer, be a master of yourself,” he says. “This is a perfectly fine entry point into the philosophy. But if you miss what the philosophy is also asking of you, in terms of ethics and morals and its emphasis on the virtue of justice, how we’re interconnected and interrelated, then really, what you’ve just discovered is a recipe for being a better sociopath. Which is not what stoicism is.”

OK, good. Because if stoicism differentiated itself from its contemporary philosophies it was on precisely this point, as Holiday describes: cynics weren’t interested in politics, “the Epicurean gets involved in politics only if they have to, and the stoic gets involved in politics unless something prevents them”.

Holiday’s own most public political intervention came in 2016, when he wrote an open letter to his Republican father, asking him not to vote for Trump, then another in 2020. Holiday himself is a “lower case-c conservative”, he says. “I like the idea of being responsible for yourself. I live in Texas, and I hunt, and I own my own business, and I generally like to be left alone. But directly from my study of stoicism, I have a very strong social conscience, that makes me find almost everything that Republicans stand for to be completely abhorrent.” The 2016 election, he remembers with vaudeville horror, “sent my wife into labour”. Sidebar on that baby, the first of two sons, with Samantha Hoover: his stoical approach to parenting, The Daily Dad: 366 Meditations on Parenting, Love and Raising Great Kids, is much less annoying than I expected, tending towards the “this too shall pass” school of family life.

But back to 2024. “I remember in 2016, not knowing what world this was going to be. Today, it’s not like Americans are facing some unknown – 70-odd million of us want to go back. But on a larger level, I guess people have always been insane. The annals of history are insane.”

What is he going to do if Trump wins, I ask. Surely that’s going to put his stoic acceptance of external environments at odds with his passionate belief in a fair society?

“My gut tells me that Kamala’s going to win and by a fairly large margin,” he says. “But I could be fooling myself.” Do stoics even do that? I guess some of them must.

The 10th-anniversary edition of The Obstacle Is the Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumphs, by Ryan Holiday, is out now (Profile, £16.99). To support the Guardian and Observer, buy your copy from bookshop.theguardian.com. P&P charges may apply. Ryan Holiday will be live at the Troxy in London on 12 November. Tickets can be purchased here.