Saoirse Ronan’s new film The Outrun is building Oscar buzz following rave first reviews.

Directed by Nora Fingscheidt and adapted from Amy Liptrot’s 2016 memoir of the same name, The Outrun tells the story of a young woman named Rona who, after finishing rehab for alcoholism, returns home to the Orkney Islands in Scotland in an attempt to stay sober.

In a four-star review, The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw wrote: “In every shot and every scene, mostly in closeup, Ronan carries the film with her unselfconsciously fierce and focused presence. Out-of-control-drunk acting in montage is a difficult thing to bring off – as is the representation of precarious sobriety – but she does it with intelligence and plausibility.”

The Independent‘s Clarisse Loughrey also gave the film four stars, writing: “The Outrun’s true tether is Ronan, and here she works to all her greatest strengths. The film wraps entirely around her, yet she’s far too honest an actor to ever play up to the audience’s expectations of a woman in crisis.”

In Little White Lies‘ gushing review, Katherine McLaughlin praised Fingscheidt for balancing the film with humour and “magnificent detail. The way in which she portrays the AA community of the Orkney Islands, all older men sporting chunky knits nestled beside a tiny young woman, stands out in its depiction of intimacy and vulnerability.”

iNews, meanwhile, suggested that The Outrun could see Ronan finally clinch her first Oscar. “She is astonishing in this role, able to harness both fragility and determination in equal measure. She dances alone as if exorcising demons from her body, pretends to conduct waves on the beach with unparalleled joy.

“Could this be the film Ronan finally wins an Oscar for? She would certainly be a worthy winner. Hers is a full-body performance: Rona is as effervescent even in sobriety as the magnificent wilderness she has chosen as her remedy.”

The Outrun is in UK cinemas from September 27.

The Wild Islands of Orkney

It’s a wonder the wild islands of Orkney have never truly been captured on the big screen before. That changes this weekend with the raved-about release of The Outrun, starring Saoirse Ronan as the recovering addict Rona, and co-produced by Ronan and her husband, Jack Lowden of Slow Horses fame. Partly shot on the islands two summers ago, it is based on the Orcadian writer Amy Liptrot’s bestselling memoir about alcoholism, mental health and the potential of the sea, the land and nature to accelerate recovery. It is about transformation, with her move back to Orkney from London the trigger.

For me, Orkney is something to crave in itself, particularly if you love everything wild. There are 70 islands to explore, with each one gifted a different layer of history, from the Mesolithic and Neolithic to the Pictish and Viking. Encounters with the prehistoric site Skara Brae, the Ring of Brodgar stone circle and Kirkwall’s magnificent St Magnus Cathedral are utterly wonderful but, beyond those most famous sites, the island shorelines groan with wildlife and there are sea stacks alive with kittiwakes and pocked with gurning sea caves.

I was last on the islands a couple of years ago and instantly felt the magnetism of the place and its people. Mainland, where the vast majority live and visit, is the gateway and home to Kirkwall airport, but I would far rather sail with NorthLink Ferries from Thurso Bay to Stromness (90 min, from £21.05; northlinkferries.co.uk). In fact, I would argue the approach along the western edge of Hoy to Mainland is Britain’s most cinematic cruise. Once there, stay at the Ferry Inn, with neat simple rooms and a bar, within earshot of gulls fighting by the harbour (B&B doubles from £120; ferryinn.com). For most people, exploring there, perhaps with a ferry to Hoy or a drive over to South Ronaldsay, is enough for a few days; for longer visits you might fly or take a ferry to Papa Westray.

The specific location of The Outrun, the nickname given to the farm where the writer grew up, has rightly been kept a secret by the author and production crew. Instead, the tourist board will point you to the eroding peninsula of Rowe Head, overlooking the Bay of Skaill on Mainland, if you want to watch lambs at play in spring. You may hear the “wild, bubbling song of curlews and lapwings”, as Liptrot, a former RSPB corncrake officer (she volunteered to monitor the birds), puts it in her book. Seabird cities are a chief attraction and there are 13 nature reserves on the islands. Best visited in June, Noup Cliffs above the heavy seas of Westray is where you’ll find Orkney’s largest colony of gannets, guillemots and razorbills in one giant squawk-off (rspb.org.uk).

Despite Orkney’s unforgivable weather, travellers seem to fall in love with the islands easily, perhaps because of the barely believable geography. Look to Hoy’s sea stacks and you see the sandstone buttes of Monument Valley dumped into the North Sea. On Eynhallow, an abandoned monastery island caught in a perpetual swell of savage tides, there is a sense of being in a time capsule — it was deserted after a plague epidemic in the 19th century. If Scotland has an Atlantis, this is it.

I would recommend a visit to St John’s Head, the UK’s highest vertical cliff, on Hoy. Liptrot describes gazing out longingly from there and how “the colours of the sky and the light on the sea change all day as rapid Atlantic weather systems pass over”. Put another way, the views are enthralling but you’ll need your boots and your big coat. Stick John Fergusson’s Orkney: 40 Coast and Country Walks in your pocket.

Orkney’s Folk Tales and Magic

This is a place of folk tales too. Orkney is the land of kinfolk, the shapeshifters of the sea and the mischievous “sea trow”, a troll-like fairy. There is also plenty of talk about the Mirrie dancers, the ceilidh-dancing aurora borealis. During periods of high solar activity like this, the islands’ skies are in full bloom, making winter a great time to go. The Orkney Aurora Group on Facebook is a terrific source of insider knowledge.

Kristian Cooper, who runs the guide company Sea Kayak 59° North, told me about the “grimleens”, a beautiful Orcadian word to describe the first or last gleams of daylight. It is the perfect expression of the golden haze these islands do best. If the preview of The Outrun is anything to go by, it will look so beautiful on the big screen.

I joined Cooper kayaking Eynhallow Sound along the coast of Mainland to the Broch of Gurness, and every sift of my paddle was met by a glimpse of dramatic history: a crumbling jumble of drystone walls, stone-floored galleries and, most gripping of all, a circular tower from the Iron Age. “There’s so much history you can trip over it,” he said, stroking his Viking-length beard. “Not to mention, you rarely meet anyone else.” If you end up there one day, say hi to the seals (half-day from £70; seakayak59.co.uk).

Of all the cinematic seascapes to explore, perhaps none is better than Scapa Flow, a deep protected natural harbour where the waves soften and the history builds. This former naval anchorage, cradled by the islands of Mainland, Hoy and South Ronaldsay, has become a curious draw because of the world-class wreck diving. Also of interest are the concrete-block causeways that make up the Churchill Barriers. Built in the 1940s, largely by Italian prisoners of war, these ramps were introduced to protect Royal Navy moorings after a German U-boat entered the harbour through Holm Sound and sank a battleship. These days, the view is of a series of sculpted bays and fudgy sands. When Liptrot was searching for calm during her rehabilitation, she found it there with the Orkney Polar Bears wild swimming club. If you’re a keen bather, there’s nothing to stop you taking a dip too.

I would also recommend snorkelling the shallow blockship wrecks sunk in the channels between Burray, Glimps Holm and Lamb Holm with Kraken Diving (guided shore dives from £175; krakendiving.co.uk). These half-drowned vessels and rusting top decks are marked by an unearthliness. Backlit in summer, they are ghostly beacons. In winter, struck by shivering waves, churn and echo, they are daunting and disquieting.

The Islands of The Outrun

Another wellspring of mystery and a key influence on The Outrun is the island of Papa Westray (aka Papay), population 70. It is accessible by the world’s shortest scheduled flight with Loganair, from neighbouring Westray, breezing in within 90 seconds (from £17; loganair.co.uk). To stay on the island, Beltane House youth hostel has private rooms and bothies resembling upturned boats (room-only doubles from £62; papawestray.co.uk).

The next time I visit, I must make it to the Knap of Howar, which some say trumps Skara Brae by about 500 years as the oldest preserved houses in northwest Europe, dating to 3700BC. In fact, I would take the trip just to learn more about St Tredwell’s Chapel, steeped in the curious legend of a holy virgin who gouged her own eyeballs out in an act of love. Apparently she skewered them on a twig. It serves as a reminder that, even on this tiny speck on the map, wonder is never far away.

There is another Orcadian worth getting to know. The composer Erland Cooper can distil the essence of the islands onto record and, as I write, I’m listening to his latest restorative balm, Carve the Runes Then Be Content with Silence, which was released last week. Previously, when I thought of Orkney, the sounds were of seagulls and the cannon of waves. Now I’ll hear soaring violins and soft piano too.

Where, I asked him, would he recommend to best grasp Orkney’s magic? “Stromness, the town I was raised in with my five siblings,” he said. “A walk around the Point of Ness to see the hills of Hoy will explain all. Walk up the cobbled street that coils like a sailor’s rope to the end of the town and the edge of the world. Perhaps a selkie or gannet will keep you company.”

That the composer’s work is the perfect soundtrack to a visit is largely because he fuses a connection between music and Orkney’s nature like few else can. It is a sleight of hand that also appears in Liptrot’s unflinching words and the same deep meditation on place. That’s the thing about Orkney. It engenders an immediate connection to the soil and the sea. And, surely, that has to be good for the soul. Mike MacEacheran travelled independently

The Outrun: An Uneven Adaptation of Amy Liptrot's Memoir

This tale of addiction and healing on Orkney is faithful to Amy Liptrot’s memoir – at the cost of narrative momentum.

By

David Sexton

Amy Liptrot’s memoir, The Outrun – about recovering from the alcoholism that took over her life in London in her twenties by returning to the Orkneys where she had grown up and embracing the natural life of the islands – looks ever more a masterpiece as time goes by. It is exceptionally well written, describing chaotic and painful experiences with remarkable clarity and directness, engaging with the wild life of the islands with an intensity that makes most nature writing seem footling.

When The Outrun was published in 2016, it was immediately admired. It won the Wainwright Prize for nature and travel writing as well as the PEN Ackerley Prize, and sold more than 100,000 copies in the UK. This summer, it was adapted – heaven knows how – for the stage at the Edinburgh Festival, without Liptrot’s involvement. Now the film version is here, scripted by Liptrot with the director Nora Fingscheidt (who has made documentaries and two feature films, System Crasher, about a violently disruptive nine-year-old girl, and The Unforgivable, in which Sandra Bullock plays a woman released from prison after serving 20 years for murder). Saoirse Ronan stars and, with her partner, Jack Lowden, co-produces.

Making a drama from such a specific memoir, one so intent on its own authenticity and so well expressed in its own medium, is a dicey business. Do you stick to every documented detail or do you adapt freely? Fingscheidt named the lead Rona, not Amy, to provide some “creative distance and healthy freedom” for all, but otherwise remained faithful to the book – at the cost of not having much propulsion in the narrative.

Rona’s story is presented in three phases, intercut as memory dictates. There’s her hapless life in London’s Hackney, partying and drinking herself into aggression and oblivion, repulsing her reliable boyfriend (I May Destroy You’s Paapa Essiedu). There’s her newly sober life in Orkney, time spent with both her separated parents: her bipolar farmer father (Stephen Dillane) and her evangelical mother (Saskia Reeves, who is particularly good). But there is also much time on her own – on the cliffs, by the shore and in the sea. As a navigation aid through these chopping and changing eras, her hair changes colour, dyed an electric blue in London, growing out as she perseveres in abstinence, ultimately becoming an orange flame of assertion. There are also flashbacks to her childhood and the family troubles that remain with her.

The filming is almost documentary in style, close-up and reeling in the London scenes, calmly taking in the landscape in the Orkneys, the editing changing pace to fit Rona’s mood. A great part of the film’s appeal, as of the book itself, is how vividly it transports you to these remote, windswept, sea-pounded places, all filmed in situ. We see wonderful seals. A terrific surging score by John Gürtler and Jan Miserre picks up the sounds of the storms and the waves, to make a rhapsody, startlingly distinct from the drum and bass Rona loves.

The dialogue is humdrum, perhaps improvised – “I can’t do this any more,” says the boyfriend inevitably, breaking up with her – and there’s a lot of voiceover directly from the book, too, some of it fanciful: “High on fresh air and freedom on the hill, I study my personal geology. My body is a continent… when I orgasm, there’s an earthquake.”

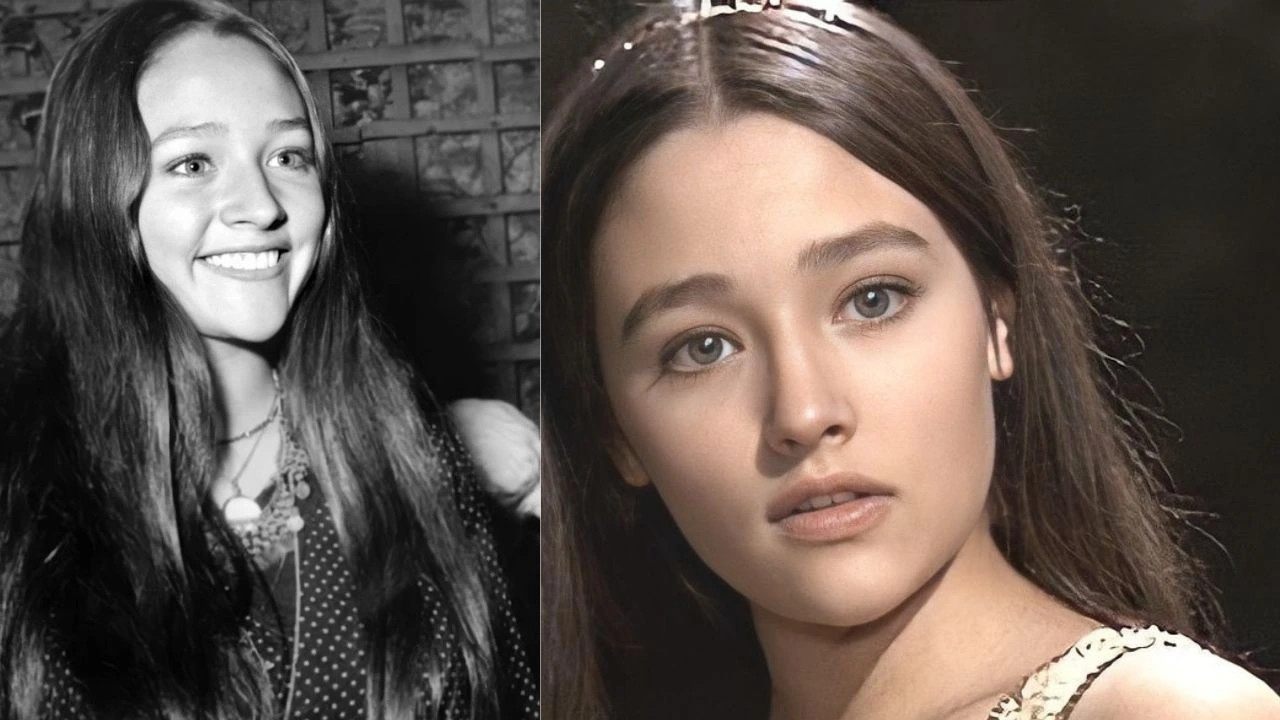

Ronan – whose astonishing face at times resembles a carved, gothic Madonna – is excellent throughout, always edgy, never making herself easily likeable, always isolated. “Watching the film, I feel that she makes a better version of me than I do,” Liptrot has humbly said.

She is oddly not sexual, though – there’s an absence. “A lot of nature writing is quite chaste, so I wanted to put the sex in nature writing,” Liptrot has said. In The Outrun she emphasises that her love of nude wild swimming is cathartic, offering transformation and escape, like intoxication: “I am so thirsty and full of desire.” Rona favours a one-piece. Likewise, Liptrot recounts taking off all her clothes and running round the Ring of Brodgar stone circle one midsummer dawn: here, it’s just an affectionate night-time hug from Rona.

Having somehow to wind up, the film ends with a mightily orchestrated climax, Rona alone, enraptured, conducting the wind and the waves, entirely at one with natural ferocity, an over-the-top scene that failed to enrapture me. The Outrun almost makes a great success of an improbable adaptation. In future, the book will no doubt bear Saoirse Ronan’s features on the cover, but still show us Amy Liptrot’s true face inside.

“The Outrun” is in cinemas now

Finding Ecstasy in 'The Outrun'

Saoirse Ronan gives a stunning performance in uneven exploration of addiction and isolation

In Jia Tolentino’s essay collection Trick Mirror, the writer recalls her childhood in Houston, Texas, where she attended 20,000-strong superchurch services each weekend. There was a jumbotron, a pipe organ with over ten thousand pipes and people singing loudly in unison, standing and crying.

There was a meaningful sense of both abandon and connection. It wasn’t until years later when Tolentino went clubbing and tried MDMA that she felt a similar sensation – ecstasy.

“I have always found religion and drugs appealing for similar reasons,” she writes. “(You require absolution, complete abandonment, I wrote, praying to God my junior year.) Both provide a path toward transcendence – a way of accessing an extrahuman worlds of rapture and pardon that, in both cases, is as real as it feels. The word ‘ecstasy’ contains this etymologically, coming from the Greek ekstasis – ek meaning ‘out’ and stasis meaning ‘stand’. To be in ecstasy is to stand outside yourself.”

Of course standing outside yourself isn’t always a form of ecstasy, and complete abandonment isn’t always a form of rapturous connection. To stand outside yourself can also be a form of survival, disassociation and dysfunction.

In The Outrun, Saoirse Ronan plays Rona, who we meet when she’s living in London. She's joyously losing herself to the neon haze and thumping beats on club dancefloors, and it’s in one of these nightclub settings where she encounters Daynin (Paapa Essiedu), who becomes her longterm boyfriend. Rona doesn’t know the line between losing herself and abandoning herself, drinking to the point of belligerence, blackouts and obliteration. We see her start fights, hit people and fall into a canal. Drinking - the very activity which allowed her to connect with others - has now become the very thing that pushes everyone around her away.

The Outrun explores Rona’s relationship with loneliness beautifully. Based on Amy Liptrot’s critically acclaimed memoir, we experience Rona’s relationship with alcohol and landscape non-chronologically, with the story jumping from her self-destructive wild days in London, a long stint in rehab and a return to her home on the isolated Orkney islands off the northeast coast of Scotland. It's here where she spends time with her separated parents, religious convert Annie (Saskia Reeves) and bipolar father Andrew (Stephen Dillane) - whose swings from warm and passionate to cold and depressive offer a parallel to Rona’s own struggles and an insight into the unpredictable nature of what connection looked like to her growing up.

Each chapter is marked by a bone-deep sense of loneliness. An early scene in Orkney sees Rona ask a man for a cigarette in an effort to strike up a conversation, her sadness and desire for friends emanating from every pore. In rehab, she observes her peers’ engagement with animal therapy but doesn’t participate, and when another recovering addict shares his hopes for the future, Rona looks blank, stating simply, “I cannot be happy sober.” Post-rehab she moves to an isolated part of the islands, retreating from the locals’ offers of kindness, often donning headphones which blare thumping techno - muting the sounds of those around her as well as the wild landscape.

The scarred female psyche is something that German director Nora Fingscheidt has explored before, in System Crasher, the story of a traumatised girl with anger issues, and The Unforgivable, which starred Sandra Bullock as an ex-con trying to find her place in the world.

The Outrun is Fingscheidt's most formally inventive work. Not only do the non-linear structure and use of hardcore music against a sweeping natural backdrops create a sense of fragmentation; she also brings in the intellectual threads from Liptrot’s memoir, which go into folklore, history and nature facts about the Northern Isles, including tales of selkies (mythological mermaids), maritime history and bird migration paths. These threads include the use of animation, archival footage, and photographs, with a voiceover belying the film’s literary origins.

What works well on the page often proves to have uneven results onscreen. The chronological jumps are effective in revealing the extent of Rona’s self-destruction, but when combined with the intellectual threads they interrupt and dilute the sense of immersive connection to the landscape that’s vital to the film’s emotional core. The shots of Orkney’s wild, windswept cliffs and crashing waves are impressive, and may add to an intellectual understanding of the landscape, but the fragmented structure and diversions hinder emotional connection to it.

These issues lie in the direction, not Ronan’s performance, which is the most mature of her career. Her portrayal of Rona’s aggression, desperation, self-judgement and sadness are beautifully, painfully authentic, layered with a deep understanding of the character’s history and the self-destructive cycle she finds herself trapped in. The moments where Ronan begins to show us Rona’s connection to the landscape and her slow healing are often interrupted, disrupting the emotional progression and saturation of the piece, as well as the pacing itself.

The most impactful scenes are when Fingscheidt lets the camera linger with Ronan as she finds moments of connection. Whether she's forging a gentle fireside connection with someone, slowly submerging herself in sea water, or, as in the final scene, ecstatically conducting ocean waves. In these moments we feel Rona finally stop abandoning herself. Instead she stands resolute, the life-affirming possibility of connection emanating from the screen. It may not be ecstasy, but it’s self-acceptance.