It might be easier to picture spiderwebs covering candelabras in Dracula’s mansion than tucked into a first aid kit, but researchers are trying to change that.

A study published in the ACS Nano journal this month revealed that Scientists have made a fake version of spider silk developed for treating wounds. So far, they have had success testing the material on joint injuries and skin lesions in mice.

While it looks thin and flimsy, real spider silk is actually one of the strongest substances on Earth. It’s even technically stronger than steel for a material of its size.

“Spider silk is one outstanding fibrous biomaterial which consists almost entirely of large proteins,” said a 2008 study published in the Prion journal. “Silk fibers have tensile strengths comparable to steel and some silks are nearly as elastic as rubber on a weight to weight basis. In combining these two properties, silks reveal a toughness that is two to three times that of synthetic fibers like Nylon or Kevlar. Spider silk is also antimicrobial, hypoallergenic and completely biodegradable.”

There’s a catch, though. The American Chemical Society explained in a press release that the material is hard to obtain, since spiders are territorial.

Silkworm silk is much weaker than spider silk, the 2008 study explained. However, silkworms are easier to breed and spiders are often cannibalistic.Due to the challenges of collecting spider silk for human purposes such as bandages, scientists have been working to develop easier-to-obtain versions of it.

These new peptides followed a pattern found in the protein sequence of amyloid polypeptides. They helped the artificial silk proteins fall into an orderly structure when folded, and they prevented them from sticking together.

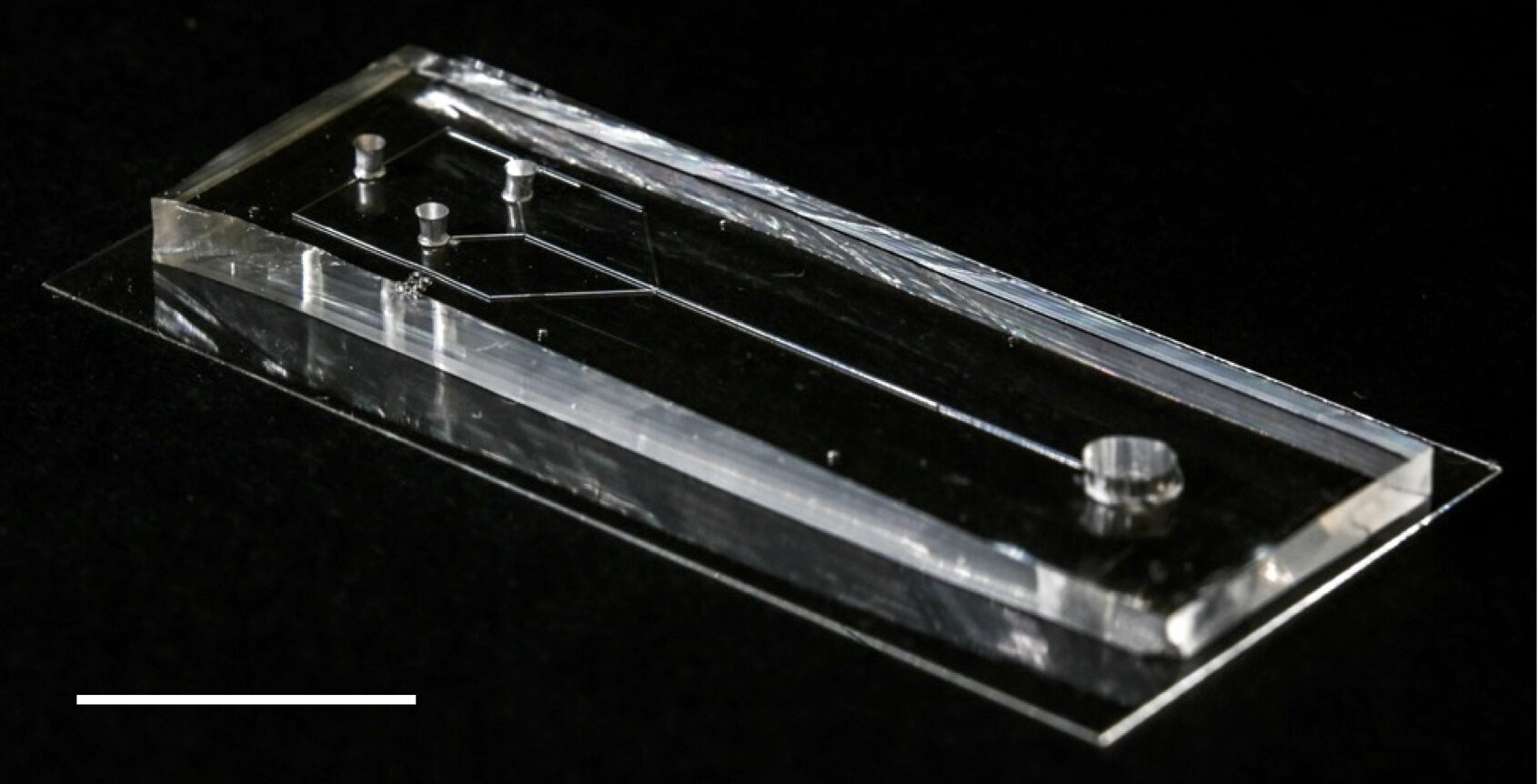

Next, the team used tiny, hollow needles attached to the nozzle of a 3D printer to create thin strands of the protein solution. These strands were drawn into the air and spun together to make a thicker fiber, almost like a giant mechanical spider spinning a web.

From there, these silk fibers were used to make prototype wound dressings. Researchers applied the dressings to mice with the degenerative joint disease osteoarthritis and mice with chronic wounds caused by diabetes.

“Drug treatments were easily added to the dressings, and the team found these modified dressings boosted wound healing better than traditional bandages,” said the American Chemical Society.

For instance, mice with osteoarthritis showed decreased swelling and repaired tissue two weeks after treatment. Diabetic mice also saw significant wound healing after 16 days. Going forward, the team believes that the biocompatible and biodegradable fake silken bandages might have more applications in medicine.