It’s 40 years since the visit of US President Ronald Reagan came to Galway – a visit that wasn’t exactly met with overwhelming delight, as Galway campaigner Brendan Speedie Smith recalls four decades on from co-leading the protests.

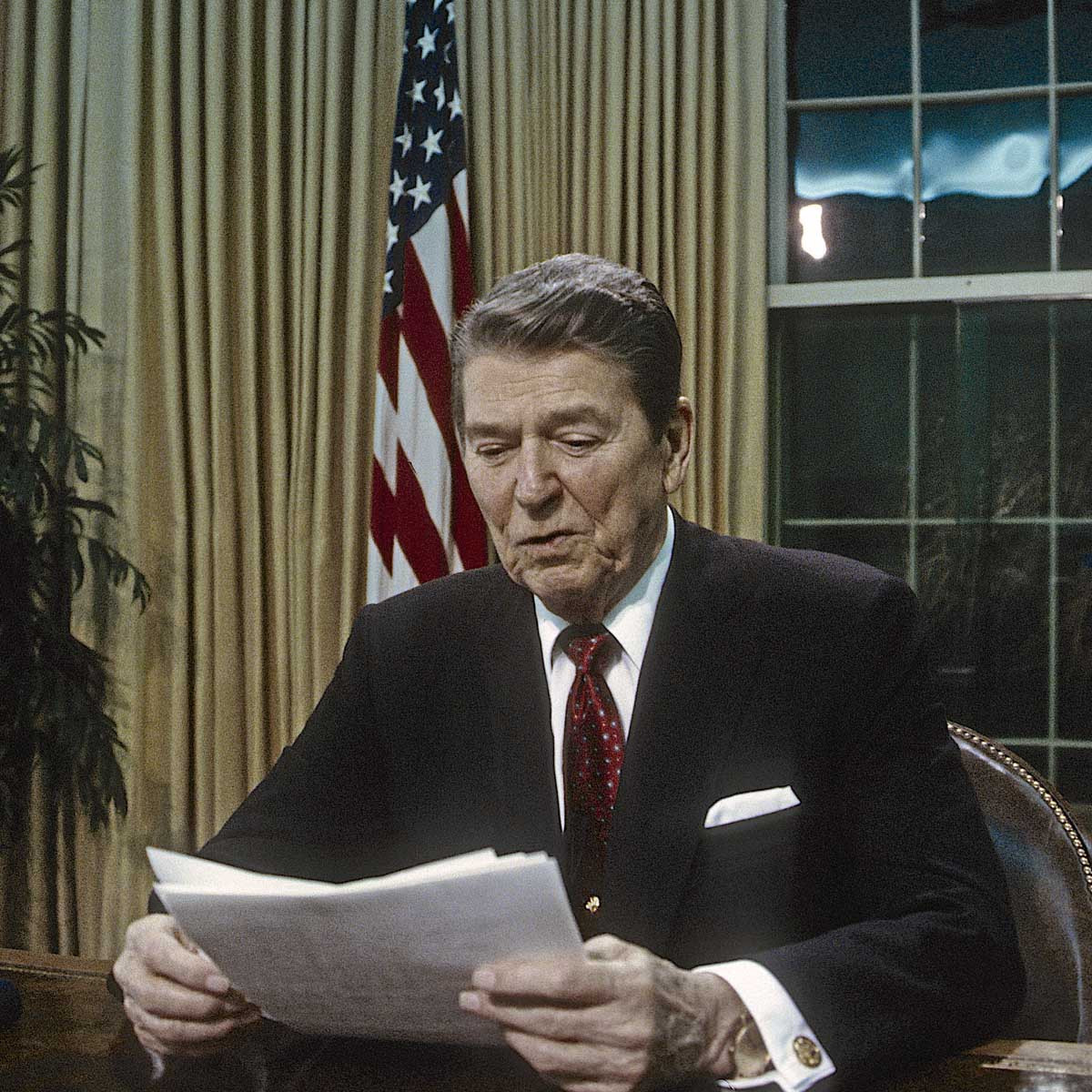

As the highlight of the celebrations to mark 500 years since Galway was granted self-governing city status by King Richard III, US President Ronald Reagan came here on June 2 1984 to receive the Freedom of the City and to be conferred with an honorary doctorate-in-law at University College Galway.

In what was a US Presidential election year, Reagan’s Republican Party were thrilled with the opportunity for him to emphasise his Irish ancestry which they hoped could help capture a significant segment of the influential Irish/American blue-collar demographic that up until then traditionally voted Democrat.

It meant that, on June 2, thousands of people from all walks of life came into the city to join thousands of Galwegians to mark a visit that had captivated the attention of global audiences. But they were not there to welcome President Reagan; they were there to condemn him, to protest against US foreign policies which had brought poverty, destruction and death to millions of civilians across Latin America, South Africa and the Middle East.

The Anti-Reagan Movement Takes Root in Galway

The seeds of the protest were sown long before Reagan’s arrival. Many in Ireland were painfully aware of these global issues. As elsewhere, concerned Irish youth had their bedroom walls and tee-shirts emblazoned with justice/anti-war themes and clubgoers danced to the politicised music of Jam, Specials, Marley, Bronski Beat, Springsteen and others.

That March a number of us hosted a public gathering in the Atlanta Hotel on Dominick Street to discuss organising a peaceful protest against Reagan’s visit. As would be expected, there were members present from left wing parties, CND, artists, trade unions and students’ unions.

Senator Michael D. Higgins, the doyen of progressive campaigns, was there. But there were others too who were not the ‘usual suspects’ for such an event – including personnel from the Galway-based corporations, businesspeople, priests and nuns. A committee was established with an officer board – Fintan Coughlan, Dermot Guy and myself with poet Kathleen O’Driscoll as PRO.

This diverse grouping, known as the ‘Galway Campaign against Reagan’s Foreign Policy’, coordinated a range of actions in the months preceding the visit. A stunning Sam Hand designed poster with an iconic Claddagh Ring bleeding heart motif and the headline ‘Ronald Reagan Heartbreaker’ decorated walls everywhere.

Margareta D’Arcy, recently returned from Nicaragua, hosted open discussion evenings at her house; Pete Sammon and Tom Conroy spent weeks making a gigantic Statue of Liberty complete with a crown of missiles.

Rock against Reagan music gigs took place in the Oasis Nightclub; poetry readings were organised by Eva Bourke in city hostelries; a peace prayer vigil in the Cathedral; packed public meeting with speakers that included feminist journalist Neil McCafferty and writer Dervla Murphy was hosted in St. Patrick’s Primary School. Fundraising events included a concert in Seapoint where musical acts included Mary Coughlan, a new star on the scene.

The Church’s Condemnation of Reagan's Foreign Policy

There was one very unusual feature to these nationwide protests against an Irish/American President visiting Ireland. It was the strong support from an unexpected quarter; from bishops and priests fundamentally against Ronald Reagan’s foreign policies. To them it was personal.

On December 2, 1980, three Catholic nuns and a lay missionary from US working in El Salvador were raped and murdered by the military. One of the nuns was Mary Clarke whose parents were Irish. The lay person was Jean Donovan who had been an exchange student at UCC only a few years previously.

The previous March, Bishop of Galway Eamon Casey attended the funeral of the country’s archbishop Óscar Romero, an outspoken critic of the regime, who was assassinated by the military whilst giving Mass. During the funeral, snipers opened fire on the crowd of mourners estimated at 250,000. Over 30 people died.

Ireland then was the most Christian nation in Europe and the majority of its citizenry were practising Catholics.

In the early 1980s, while most Irish had not travelled beyond western Europe or the cities of the USA, 8,000 Irish Catholic missionaries, aided by regular parish collections for the overseas ‘missions’, were based in over eighty countries, mainly serving amongst the poor populations across Africa, Americas and Asia.

Many of these clerics and lay workers were part of Trócaire, the Irish Catholic Church’s overseas development agency.

In 1982, Trócaire’s Sally O’Neill along with Micheal D. Higgins investigated the EL Mozote massacre in which the El Salvadoran army killed over 800 civilians. They found evidence of torture, rape and slaughter of civilians. Their report was dismissed by the Reagan administration as communist propaganda.

The Day of the Protest

Though the route of our well-stewarded protest march had been agreed well in advance with the authorities, nevertheless there was some apprehension amongst our committee about what might happen on the day.

Government concerns about the protest meant that, on June 2, over 2,000 uniformed Gardaí, detectives, armed US Secret Service and Irish Army personnel were on the streets of the city.

So we had to prepare for a worst-case scenario, namely for a confrontation with security forces possibly started by agents provocateurs.

Months earlier my fiancée Cepta and myself decided to reschedule our wedding from June to late August in case I, as one of the protest organisers, could be imprisoned.

At the assembly point in Father Burke Park on Father Griffin Road, we announced from the stage that all cans, bottles etc. were to be left behind before the march proceeded; that, should an incident occur that might provoke the Garda to move towards the marchers, everyone was to sit down on the ground; and that legal aid was available for anyone arrested.

But what unfolded that morning as the crowds gathered was positive and heart-warming.

There were parents with children, German hippies on horseback from South Galway, Franciscan monks in brown habits, nuns with painted faces carrying a coffin, priests, anarchists, pacifists, feminists, Galway Trades Council members, business owners, socialists, liberals, the non-aligned, artists, teachers, youth, students…

To the sounds of rhythmic chants, a large colourful festive parade of peace with banners held high and a giant Statue of Liberty being pulled along proceeded to the Salmon Weir Bridge side of Galway Cathedral, the closest we were allowed to get to the university conferring.

There we were met by lines of Gardaí.

A Day of Symbolic Actions

A number of symbolic events then took place. On stage, university academics along with War of Independence republican veteran Peadar O’Donnell presided over a ‘deconferring’ where three holders of NUI honorary doctorates returned their degrees. This was followed by a number of graduates, including myself, collectively setting fire to our degrees.

When the Presidential cavalcade came over the bridge it was met by a mighty roar from the 4,000 or so protestors.

Whilst 500 guests waited for Reagan to appear onstage in UCG’s Quad lawn, inspired by international chart-topping hit anti-war song ‘99 Red Balloons’ by German band Nena, we released 99 black balloons into the air which floated over the university just before the ceremony began.

At the official university ceremony, heavy rainfall led to President Reagan having to cut short his speech. As he passed us again in ‘The Beast’, the chants and shouting restarted. One protestor broke through the police cordon and threw a tomato at the cavalcade. He was promptly arrested.

The Legacy of the Protest

From our perspective, the protest was an outstanding success. It was reported by the media that only 5,000 were there to welcome Reagan on the streets of Galway and that, for large sections of the route from the Sportsground to UCG via Eyre Square, the majority of onlookers were the Gardaí.

What a dramatic change from the 80,000 that greeted US President Kennedy in 1963 and the 280,000 in Ballybrit for Pope John Paul 11 in 1979.

It was reported too by the authorities that protesters numbered 2,500. But that was deliberately lowered so as not to shock an American audience about the true extent of opposition in Ireland towards US foreign policy.

After Reagan left, the majority of protestors went downtown to socialise. I though, as the committee member responsible for legal affairs, had to spend time in the Garda Station on Eglinton Street aiding the solitary person that was arrested.

Job done, I ran quickly to Quay Street to join my friends. When I entered the Quays Bar, I could hardly believe what I was witnessing. The pub was packed with out-of-town uniformed Garda and protestors with drinks in their hands, amiably chatting and laughing together!

What a lovely Irish ending to a day when a socially and globally aware active Ireland started to crystallise.