Nationwide protests against the brutal killing of a 31-year-old medical student on August 9 in Kolkata echoed our collective anguish over a yet another rape-and-murder case in the country. Even then, justice continues to elude the victim’s family as the politics, intrigue, and conspiracy surrounding this crime deepen every passing day.

Not surprisingly, various political organisations in West Bengal and Delhi have become embroiled in a war of words, blaming each other over the ghastly incident. Meanwhile, the protests, which initially began on R. G. Kar Medical College in Kolkata, have swiftly spread across India in the form of silent marches and candle light processions.

All of this is eerily reminiscent of the 2012 Nirbhaya case, when the entire nation stood united to cry out against a yet another innocent young woman’s shocking rape and murder in Delhi. In the Kolkata case also, millions of Indians have taken to the streets and voiced their anguish and frustration over the ghastly incident.

While spontaneous and passionate demonstrations in support of women’s safety and women’s rights are an encouraging sign in themselves, they also raise a worrying question: Why do rapes continue to occur in India despite the ever-increasing public protests against this crime?

After every vehement protest against a rape-and-murder-case in India, a few more such cases hit the headlines. For instances, within a few days of the Kolkata case, a teenager was gangraped on a bus in Dehradun within a few days of the Kolkata case, a teenager was gangraped on a bus in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, on August 12. A 10-year old girl was raped and murdered on August 21 in Kolhapur, Maharashtra. On September 12, two Army officers were robbed and their woman friend was gangraped in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh.

As evident in these instances, the disturbing trend of more rapes and murders, following protests and public outcry against atrocities on women, strongly persists. Nowadays, every headline-making rape feels like a déjà vu! To put it in perspective, according to a recent news channel report, there were 31,516 rape cases registered in India last year; which amounts to 86 cases per day, and four rapes every hour!

Staring in the face of such worrisome numbers, one wonders, why do vociferous protests prove powerless against the rampant rape culture in India? Why do demonstrations and social media campaigns against rape culture achieve little to stymie it? Stating it succinctly, why do protests fail to curb rapes? While there are no easy answers, three factors might explain this stark reality: perception, politics, and patriarchy.

Protests against rape are erroneously perceived by many as an urban phenomenon with an elitist tone attached to it. It is a nefarious perception in itself; nevertheless, it does diminish the power of protests to some extent. Nowadays, thousands of social activists, political affiliates, students, members of voluntary organisations, philanthropists, and conscientious citizens pour out on the roads whenever a rape becomes a headline. Such voluntary outrage against atrocities on women seems representative of contemporary India.

However, it appears that the perpetrators themselves hardly feel deterred by public protests. More protests and more social media coverage do not translate into fewer rape cases. Perhaps, the rapists consider protests against rape a passing phenomenon that rises quickly, garners a lot of attention, and dissipates soon after. Perhaps there is too much visibility, hype, and commotion attached to our

‘protests’ for the felons to see them as foreboding. Perhaps, protests nowadays seem overly urban and sensational to communicate a strong sense of moral condemnation. Perhaps, our protests have become more spectacular and media-friendly to represent and communicate our collective outrage and pain effectively.

So also, the politics attached to rape often deflects the focus away from the crime itself, giving perpetrators a sense of security. While millions of Indians join protests to express their solidarity with the victims and to demand accountability from the government, numerous others participate just to get political mileage out of it. Unfortunately, most rape cases in India become politicised clashes in which vested interests seek to malign their opponents. When politics undermines justice, humanitarian, social, and ethical concerns for the wellbeing of the victims quickly become subsidiary to hidden agendas and power dynamics.

Politicisation of social issues, such as rape and atrocities on women, also neutralises the transformative power of protests and public anger. In such a scenario, the victim’s rights are often overlooked in a bid to politicise the incident. When politics deliberately converts a dehumanising crime into a blame game, the culprits inadvertently benefit from it as legal maneuvers hamper speedy justice. Politicising atrocious crimes only leads to superfluous posturing and sloganeering for calculated gains. As seen time after time in the past decade, when political motives highjack public protests, the rapists roam free, hiding in plain sight, while the victims run for cover in fear and shame.

Similarly, a deeply ingrained patriarchal mindset drives misogynists to employ rape as a form of punishment against women. Traditional patriarchal structures in India still breed an egregious amount of discrimination against women, which encourage men to treat them as inferior, weak, and vulnerable in general.

Worse still, patriarchy also covertly feeds and approves the objectification of women through material and sexual exploitation.

Since a patriarchal mindset considers women’s subjugation a normal social practice, it also treats sexual violence as an effective means of overpowering women. Indian women will continue to become victims of sexual violence, such as rape and murder, so long as the biased patriarchal social systems prevail in India; so long as women remain deprived of the dignity and respect they deserve; so long as they continue to face discrimination and dehumanisation from a male-dominated society. Unfortunately, protests against rapes fail to desist bigoted men from committing sexual crimes against women because the latter remain ensconced within the walls of their misogynist biases.

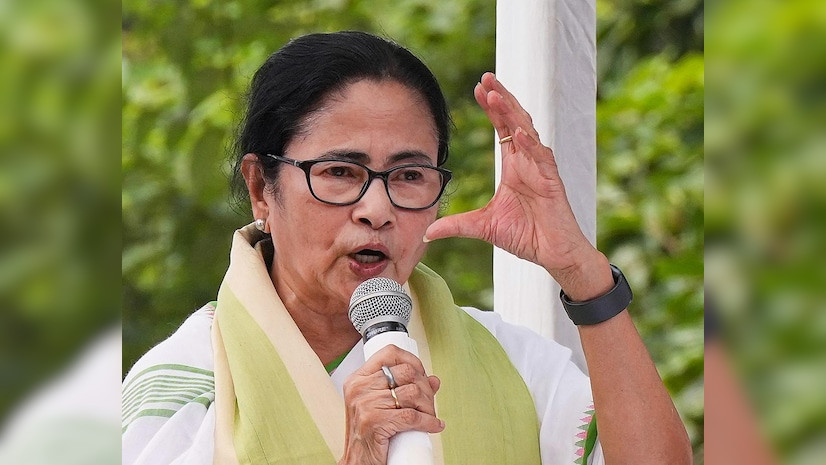

West Bengal’s new Anti-Rape Bill is positioned as progressive and critical legislative reform aimed at addressing sexual violence against women and children by instituting ‘exemplary and severe consequences’ that will act as a deterrent. However, in reality, the bill is a tool for improving optics and serving the political interests of West Bengal’s TMC government following the widespread protests and outrage over the R G Kar case, where a trainee doctor was raped and then murdered in Kolkata.

The incompetence that characterised the handling of the R G Kar case cast long shadows on the State government. The pan-India protests, a doctor’s strike that wouldn’t quell, and palpable public anger all brought the government’s inaction and apathy under critical focus, with even the Supreme Court questioning the State’s fumbling of the case.

A brooding sense of doubt over the power of protests to curtail atrocities against women lingers on because of the frequency with which violent crimes continue to occur in India, despite forceful protests after each such incident. While the accused were quickly arrested, convicted, and hanged in the 2012 Nirbhaya case, neither the widespread protests that erupted in its aftermath, nor the fate of the convicts, daunted other rapists across the country.

In the past decade, such heinous crimes have only continued to shock the nation at regular intervals. In particular, the Badaun case in 2014, the Kathua case in 2018, and the Lakhimpur Kheri case in 2022. Young women were subjected to rape and violence in these instances even after much hue and cry over the Nirbhaya case. If the protests, advocacy, and anger that accompanied these crimes had generated even a semblance of deterrence, perhaps, the recent Kolkata rape and murder case would not have occurred at all.

While a faulty perception of public protests persists, while the politics besieging sensationalised rape cases thrives; and while an impervious patriarchal system survives, public outrage alone will never eradicate rape, rape culture, or rapists from India. On the contrary, the rapists seem will continue to develop an immunity to the sociopolitical, legal, and moral pressure exerted by public protests all over the country.

Since protests are reactive by nature, something more proactive is required. Perhaps, a paradigm shift in the way women are perceived, judged, and treated in society might make a difference. It might even become a potent antidote to the menace of rapes in India.

To salvage a worsening political situation, The West Bengal government resorted to a quick fix to assuage public demands for reform and action by introducing the Aparajita Bill, which is little more than an effort at populist pandering. But this political strategy comes at the cost of actual reform that could have addressed sexual violence; by basing legislation on the fiction of capital punishment acting as a deterrent and tougher sentences reducing the perpetuation of sexual offences, the government has wilfully sacrificed an opportunity to make women safer in reality.

The most notable amendments the Bill makes include making capital punishment mandatory for rape if the victim dies or is left in a vegetative state as a result of the assault or the injuries sustained during it. Section 66 of the BNS, which deals with this, on the other hand, prescribes rigorous imprisonment between 20 years to life or death, as per judicial discretion. The prescription of a mandatory death sentence is an unheard-of statutory provision, given that mandated capital punishment for crimes is considered unconstitutional and a form of legislative overreach.

Further, by amending the BNSS provisions, which deal with procedural and evidentiary rules, the new law changes timelines for investigations and trials. Police investigation of sexual offences has to be now completed within 21 days, as opposed to the BNSS’s timeframe of two months. Trials, according to the Bill, have to be concluded within 30 days from the filing of the chargesheet, replacing the two-month period the BNSS affords. In addition to amending the quantum of sentences provided in the POCSO Act, 2012, the Bill allows special courts thirty days to conclude trials, replacing POSCO’s provision of one year.

The Bill is aimed at improving optics and is a calculated political strategy. The West Bengal government is merely trying to appease the public and alleviate public anger through a populist move that allows the government to appear tough on crime and as flag-bearers of women’s safety without making any meaningful policy intervention, infrastructural changes, addressing social and institutional misogyny, or acknowledging the role of patriarchal frameworks and pervasive rape culture in the perpetuation of sexual violence. This is populist politics that serves the TMC, not the women or children who will continue to be vulnerable to sexual violence even if the Bill is enacted into law.

Knee-jerk, public responses to sexual violence always include demands for death, public executions, or torture and castration of rapists. So much so that even extra-judicial killings in cases of sexual violence find favour and are heralded. Society, like governments, seems wholly uninterested in addressing the real causes that make sexual violence so pervasive and justice out of reach for victims. Reactionary calls for the death of all rapists and harsher punishments are par for the course for public discourse immediately following highly publicised instances of sexual violence.

These responses stem from sentimentality and outrage when confronted with the heinousness of rape, as well as a collective cognitive dissonance that views rapists as existing firmly outside the bounds of normal society, a perspective that absolves our society and culture for their role in upholding structures and narratives that allow sexual assault to be committed with impunity. But this disregards the fact that the death penalty is not a deterrent. Additionally, Indian statutory laws dealing with sexual violence are, for the most part, adequate in terms of punishments prescribed, especially following amendments made in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya case.

While state focus on punitive action in response to sexual crimes that garner considerable public attention is not a new phenomenon or one specific to Bengal, the motives behind rushing the Aparajita Bill seem to be solely political. The dubious legality of the mandatory death penalty prescribed jeopardizes the fate of the Bill – and that is if it ever receives presidential assent – makes a strong case for the TMC government rushing such a Bill merely for appearances’ sake.

The Supreme Court, in its 1983 ruling in Mithu v State of Punjab found that statutory provisions for mandatory capital punishment are unconstitutional and struck down Section 303 of the Indian Penal Code, which prescribed a mandatory death penalty for convicts who commit murder while undergoing life imprisonment, on grounds of being violative of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution.

The Court also found that such mandatory prescriptions for capital punishment infringe on the judiciary’s right to exercise its discretion. The Court, in its majority opinion, held, ‘So final, so irrevocable and so irrestitutable is the sentence of death that no law which provides for it without involvement of the judicial mind can be said to be fair, just and reasonable. Such a law must necessarily be stigmatised as arbitrary and oppressive.’

Apart from concerns of constitutionality, pending approval, the Aparajita Bill joins a list of similar populist pieces of legislation that are yet to be enforced. Andhra Pradesh’s Disha Bill, 2019 and Maharashtra’s Shakti Bill, 2021, which sought to amend the Indian Penal Code (IPC), the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and the POCSO Act still haven’t received presidential assent or the Centre’s approval; and this could very well be the fate of this Bill as well.

Similar to the Aparajita Bill, the Disha Bill increased the quantum of punishment for various sexual offences, included the provision for capital punishment for certain crimes, trimmed the timeframe for investigation and trial, and even added new offences to the IPC. The Shakti Bill, modelled on Andhra Pradesh’s Bill, made similar changes. However, neither bill has yet received the President’s assent.

Though the Aparajita Bill was unanimously passed by the State Legislative Assembly, West Bengal’s Governor didn’t give his assent, instead reserving it for the consideration of the President. A Raj Bhawan communique noted that the Governor pointed out defects in the Bill and warned the government not to ‘act in haste and repent at leisure’.

Akin to these Bills, the West Bengal Bill is also likely looking at an endless wait before it becomes law. And in the meantime, the reality for women in the State will remain unchanged, with no meaningful interventions made to address sexual violence or improve their safety.

The death penalty has been proven not to be a deterrent; therefore, this is a hollow policy intervention which is not rooted in facts and betrays a lack of understanding of sexual violence. The notion that the death penalty has a deterrence effect has long been rubbished. Numerous studies and analyses have found that capital punishment neither has a significant deterrence effect nor does it reduce crime rates.

The Bill explicitly claims that it seeks to deter sexual violence. But there is no factual basis to support that this can be achieved through its implementation. Project 39A’s 2023 report found that, of all the death sentences awarded in that year, 53.3 per cent were for sexual offences, yet rates of sexual violence have remained high. In fact, in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya case, when India amended its criminal laws relating to sexual offences, including the addition of the death penalty for certain crimes, data shows that there was no decrease in cases reported in the following years. There was, actually, a considerable increase in reported rape cases in the years following the amendment – and this trend continues – than in the immediate three years preceding it.

In fact, the 2013 change in rape laws to include the death penalty was antithetical to the Justice Verma Committee’s proposal. The Justice Verma Committee, which was appointed to advise on amendments to criminal law concerning sexual violence, in its recommendations categorically rejected the death penalty calling it a ‘regressive step in the field of sentencing and reformation’ and noting that capital punishment doesn’t act as a deterrent for sexual violence.

The Aparajita Bill, apart from seeking to be a deterrent, also seeks to deliver swift justice. However, capital punishment does anything but ensure that, only drawing out the legal process longer. Between conviction and execution, there are numerous steps and safeguards, including appeals and mercy petitions, which can years or decades to go through, making speedy justice unfeasible. As of December 31, 2023, 561 people were on death row, but in the last decade, India only saw five executions – four of which were the convicts in the Nirbhaya case.

The Bill detracts from real issues surrounding sexual violence and is a missed opportunity to make meaningful legislative reforms and policy interventions that benefit women and ensure their safety. Instead, the government slapped a band-aid on a systemic and structural issue and patted itself on the back for making women safer, even though it didn’t. And this, precisely, is the most egregious failure of the West Bengal government. In introducing a self-serving, politically motivated bill, the West Bengal government chose to curry political favour by dismissing the prospect of real reform and sidelining women’s needs.

And by wilfully misrepresenting the problem of sexual violence as something the death penalty or harsher punishments can solve; such political interventions only diminish the possibility for real change through societal accountability and restructuring by completely invisibilising the role society plays in the perpetuation of sexual violence by upholding patriarchal frameworks and reinforcing rape culture.

According to NCRB data, the conviction rate among rape cases that went to trial was a scant 2.56 per cent. This, combined with abysmally low rates of reporting (with some data suggesting that 99.1 per cent of cases go unreported), renders harsher punitive measures or the death penalty futile in addressing sexual violence, particularly given the existence of a plethora of barriers to reporting crimes and securing convictions.

Sexual violence cannot be addressed meaningfully without maintaining sustained social and political efforts to address institutional misogyny, police apathy, lack of sensitisation among medical staff, inadequate and unsafe infrastructure, patriarchal frameworks that normalise rape culture and legitimise gendered notions of the right to public spaces, lack of gender sensitisation, and efforts to introduce legislation concerning sexual violence and women’s safety that takes an informed, educated, and factual approach.

The reason such populist quick fixes are legislated is that governments don’t feel inclined to do the hard, long-term, and expensive work of addressing systematic and structural issues that contribute to sexual violence. Women and their safety have long been treated as political props by members of the government, who use them to make impassioned speeches and rally political goodwill, only to promptly discard these issues until the next time they need to game public perception in their favour. But sexual violence is a threat to India’s 690 million women, and the issue cannot be subjected to the political whims or ulterior motives of political actors. Legislating for self-serving political interests instead of the benefit of the citizenry is a mockery of representative democracy.