The Albanese Government's argument that gambling advertising is needed to sustain free-to-air broadcasters, while deeply problematic, is also an opportunity to acknowledge and address the unhealthy state of media policy in this country. It’s an opportunity to highlight why media policy reform needs to centre the needs of communities, especially under-served communities, and their imperilled rights to safe, reliable and relevant news and information. The Albanese Government has inadvertently reminded us that media policy has for too long been driven by the interests of corporate media and associated interests, rather than the public interest.

Senator Sarah Hanson-Young, The Greens spokesperson on communications, called the Government’s excuse that gambling ads are needed so people can watch local news in regional and rural Australia “absurd”. “If the cost of local journalism is gambling addiction, we’re broken, we really are,” she said, suggesting that we have to “up our ambitions” in approaches to funding public interest journalism.

The Critical Question: Funding Public Interest Journalism

Unfortunately, as Croakey has pointed out in various submissions, there has been much less attention to measures to grow media diversity and to support innovative models seeking to better meet communities’ needs. That is especially important for rural and other under-served communities. Research by the Public Interest Journalism Initiative (PIJI) shows regional and rural Australia has been most adversely affected by news cutbacks, with emerging gaps in news coverage of local councils, courts and communities.

PIJI’s Australian Newsroom Mapping Project shows that, in the last three years, there has been a net loss of 121 news outlets across Australia, a sharp acceleration from previous Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) data that showed 106 news closures over a 10-year period (2008-18). Regional Australia accounts for 67 percent of outlet closures and 91 percent of service decreases.

The PIJI data also identifies 32 local government areas without any local print or digital news, all in rural or remote Australia. These data do not address journalism job losses, of which we’ve seen yet more this week, or other factors diminishing the quality of journalism (for example, the Australia Institute event heard of newsroom decision-making being driven by what’s trending on Google rather than public interest concerns, as well as concerns about the impact of under-funding of the ABC and SBS).

The News Media Bargaining Code: A Flawed but Necessary Step

We are currently waiting to hear how the Federal Government will respond to Meta’s refusal to renew media funding agreements under Australia’s innovative though flawed News Media Bargaining Code, amid threats the tech giant will ban news from Facebook and Instagram and uncertainty about Google’s longer-term intentions. Media analyst Tim Burrowes has reported, in his Unmade newsletter, that advice on the Code from the ACCC and from the Treasury is now on the desk of Treasury Minister Stephen Jones.

While the Code is problematic and has delivered neither long-term sustainability nor diversity to the Australian media landscape, Hanson-Young made an important point at the webinar that it had shown “those bastards” at Meta and Google that governments were prepared to stand up to them. If Australia had folded then, she said, there would be no way we’d be having a conversation now about protecting intellectual property in arts, journalism and other sectors from AI.

A Digital Tech Tax: A Possible Solution But With Caveats

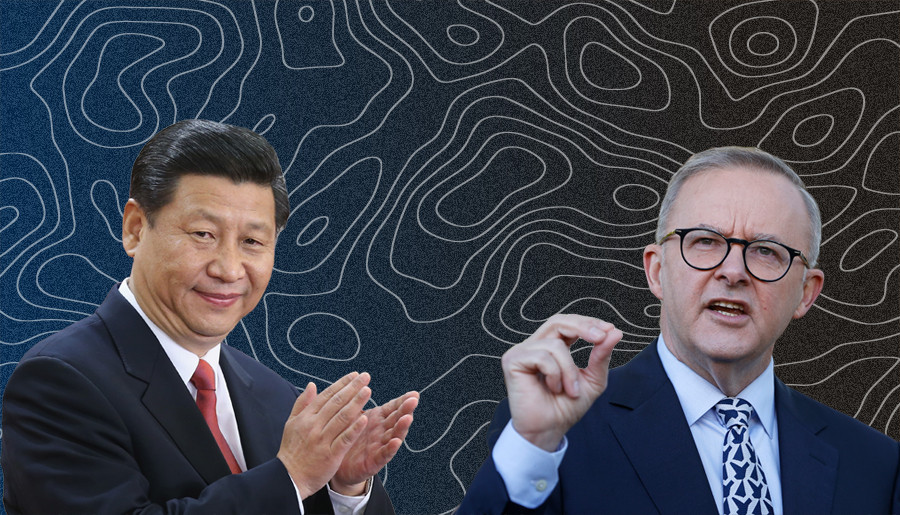

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has indicated the Federal Government is considering a digital tech tax, as are other nations like New Zealand and Canada, warning the big tech companies shouldn’t be allowed to “essentially ride free” on the backs of traditional media. Calls for such a tax, backed by the Greens, have been made locally and globally for some years, including by Nobel laureate Professor Joseph Stiglitz.

The former World Bank chief economist told an Australian Institute webinar in 2020 that he admired Australia’s efforts to get Google and Facebook to help fund journalism under the Code, but warned it should tax them if they make good on their threats to boycott Australian news over the move. Their market power was proving “absolutely devastating” for public interest journalism and democracy, and it may be time for governments to fund public interest journalism as a public good, in the same way they fund important scientific research, he told the webinar.

Such a tax has the potential to help tackle wider public health concerns, such as misinformation and disinformation, and the power of Big Tech to undermine democracy and health. But, as has happened with the Code, there would be potential to reinforce the dominance of corporate media, which often contribute to misinformation and disinformation. One of the lessons from the Code is the importance of transparency, equity and accountability in the distribution of any such tax. We know little about the distribution of moneys under the Code under commercial in confidence agreements – how much went to fund public interest journalism, shareholders or overseas.

Supporting the Not-for-Profit Journalism Sector: A Vital Step

Supporting and growing the not-for-profit sector has potential to address many of the gaps and problems with the current media landscape. The Productivity Commission’s recent inquiry into philanthropic giving was an important opportunity for developing policy to better support the NFP journalism sector.

The PIJI submission noted that developing a not-for-profit journalism sector in Australia has been repeatedly recommended and considered in parliamentary and regulatory inquiries over the past decade. “There is evidence from overseas, particularly the United States, to suggest that a NFP news sector would increase media diversity and address market failure in commercially unviable practices such as investigative journalism or in geographical, cultural, and linguistic markets of undersupply.”

However, the Communications Minister’s office has confirmed to Croakey that neither Minister Michelle Rowland nor her Department made a submission to this inquiry, despite its significance to the NFP journalism sector. Her spokespeople did not respond to our question of ‘if not, why not?’. Perhaps if the Minister and her Department had engaged with this inquiry, the Productivity Commission might have recommended public interest journalism as a standalone category for Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) status – a recommendation that was put to the inquiry by LINA, the Community Broadcasting Association, Croakey and others.

The Need for Greater Media Literacy and Advocacy

Circling back to the gambling ads imbroglio, the financial problems of public interest journalism are also closely related to declining public trust in the media, as this week’s Australia Institute discussion made clear. It was interesting to hear the politicians on the panel (Minister for Science and Industry Ed Husic and Senator Hanson-Young) speak about how important the public’s trust in media is for their work, in communicating with the public.

In undermining the social licence of media organisations by arguing gambling advertising is needed to sustain the media, the Government is thus also undermining its own credibility, in addition to the damaging optics of its support for commercial interests over public health. The webinar also heard calls for MPs to become more digitally literate to ensure effective and appropriate regulation of digital platforms. “Social media has become an essential service, but it’s not regulated like an essential service,” said Senator Hanson-Young.

If we also believe that public interest journalism is an essential service, then it’s time for all sectors, including civil society leaders and organisations, to develop their media policy literacy and advocacy, as well as critically reflecting upon how they can contribute in this space.