The world’s first vaccine for ovarian cancer could wipe out the deadly disease, British researchers say.

Experts say it could work in a similar way to the human papillomavirus (HPV) jab, which is on track to stamp out cervical cancer.

Professor Ahmed Ahmed and his team at Oxford University are identifying cellular targets for the vaccine.

They are identifying which proteins on the surface of early-stage ovarian cancer cells are most strongly recognised by the immune system.

Also, they see testing how effectively the vaccine kills mini-models of ovarian cancer in the lab.

Plus, there will be trials on healthy women to see if the disease can be prevented.

Prof Ahmed said that if the jab is successful he expects to start seeing an impact within the next five years.

Cancer Research UK is funding the study with up to £600,000 over the next three years.

How does the vaccine work?

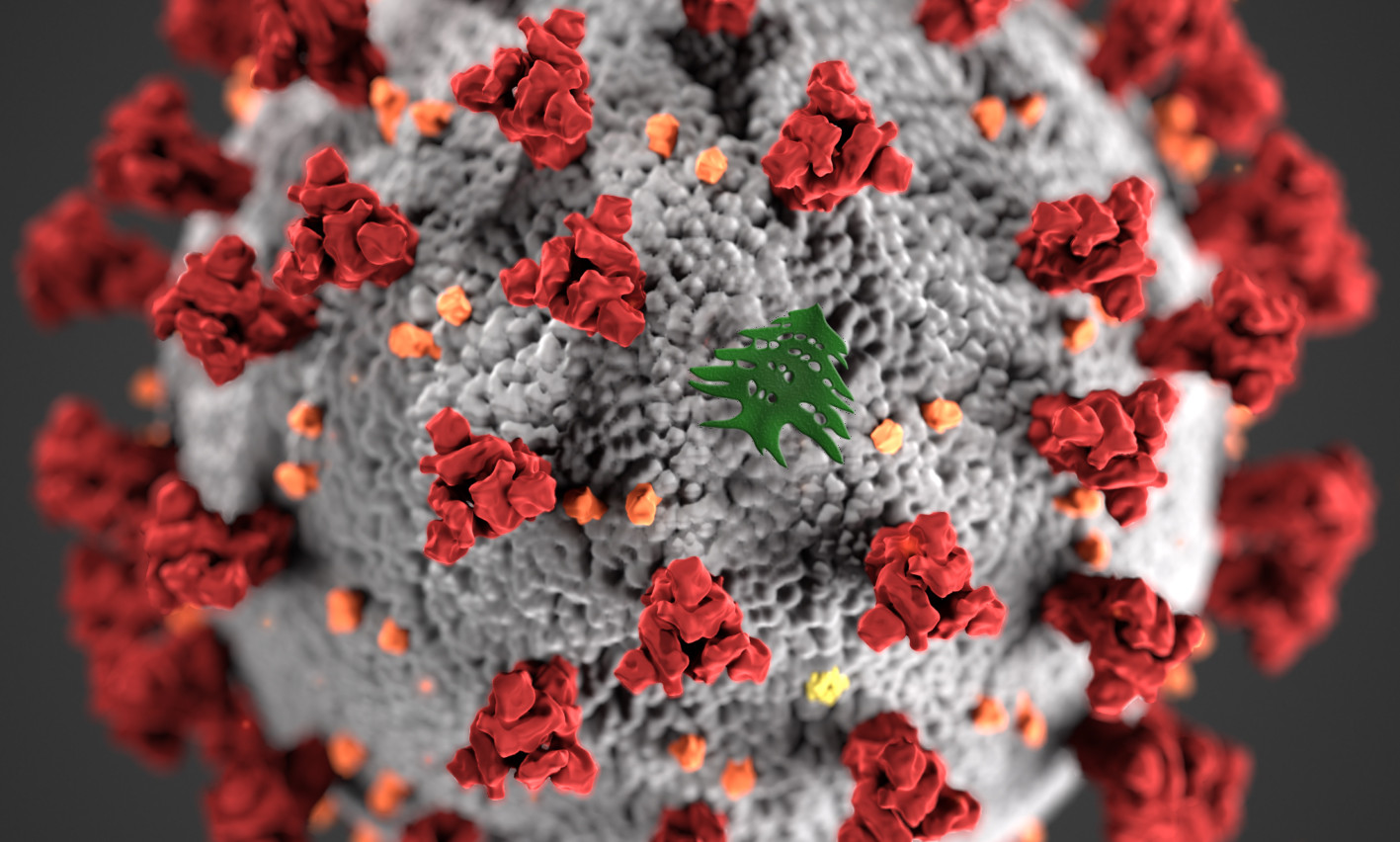

“The vaccine will teach the immune system to recognise proteins called tumour associated antigens, which appear on the surface of cells that are becoming cancerous,” explains Dr David Crosby, head of prevention and early detection research at Cancer Research UK.

“Once the immune system has been primed by the vaccine to recognise these antigens, the white blood cells will then be able to more effectively find and kill the cells which could go on to form tumours.

“In this study, scientists will find out which proteins on the surface of early-stage ovarian cancer cells are most strongly recognised by the immune system, and how effectively the vaccine stimulates immune cells to kill mini-models of ovarian cancer, called organoids.”

When will the vaccine be ready?

“It will take many years for the vaccine to go through clinical trials before it is ready for wider use,” says Crosby. “At this stage, scientists are testing the best components to include in the vaccine, by first trialling it in the lab with samples taken from ovarian cancer patients.”

Who will be eligible for the vaccine?

“Clinical trials will be required to establish which women will benefit most from the vaccine and it will take many years for the vaccine to go through those trials before it is ready for wider use,” says Crosby. “It is likely that, at least initially, the vaccine would be used in women at higher than average risk of developing ovarian cancer.

“However, the funding for this research is an exciting step towards a world where doctors can prevent ovarian cancer at an early stage, rather than treating it once the disease has already taken hold.”

Who is most at risk of ovarian cancer?

“There are a number of risk factors for ovarian cancer, such as age,” says professor Jay Chatterjee, consultant gynaecological surgeon at Cromwell Hospital. “As you age, your risk of cancer increases. People over the age of 50 have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.”

Family history can also play a part.

“Around 20% of ovarian cancer cases are believed to be caused by an inherited genetic variant,” says Chatterjee. “This is often the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.

“If you inherit a variant of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, you have a much higher risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer than those who haven’t got the gene.

“Speak to your GP if there are cases of ovarian cancer and/or breast cancer in your family.”

Some research suggests that endometriosis, smoking and diabetes can also increase your risk.

“There is evidence to suggest that if you have endometriosis, then there is a small increased risk of developing ovarian cancer,” says Chatterjee. “Studies have also found that 1 in 100 cases of ovarian cancer are linked to smoking.

“There is a 20% increase in the risk of developing ovarian cancer for those with diabetes compared to those without.”

What are the symptoms?

“Ovarian cancer is notorious for causing very minimal symptoms in the early stages, and symptoms can be non-specific, such as abdominal distension and bloating that doesn’t come and go, a new onset of abdominal and pelvic pain that you feel most days, nausea, and fullness,” says Mr Saurabh Phadnis, consultant gynaecologist and gynaecological oncologist at London Gynaecology.

“Also, urinary frequency and changes in bowel habits, a loss of appetite and weight, and any lower abdominal lumps.

“Because these symptoms are so non-specific, being aware and alert to changes in the body is essential. If you have any of these symptoms that are persistent you should seek immediate medical help with your GP.”

How is ovarian cancer treated?

Treatment for ovarian cancer is usually a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and specialised targeted drugs.

“The type of treatment and order a patient has it in depends on their preferences, the extent of the disease, previous surgeries and treatments, and their genetic background,” says Chatterjee. “The doctor will always discuss all treatment options with the patient to develop a treatment plan that will fit best.

“After completion of the initial treatment; the patient will enter a close follow up/surveillance program, where they will be seen by a specialist team in regular intervals and discuss any symptoms, complaints and potential changes.”

A New Era in Ovarian Cancer Prevention

The development of OvarianVax represents a significant advancement in the fight against ovarian cancer, potentially ushering in a new era where the disease can be prevented rather than solely treated.

While the vaccine is still in its early stages of development, the potential impact on women's health is immense.

The research holds the promise of reducing the burden of ovarian cancer and improving the lives of countless women worldwide.