Angelina Jolie has a fashionable way of channeling Maria Callas on the red carpet — the iconic opera singer she portrays in Pablo Larraín's new biopic, Maria.

Per the magazine, many of the storied opera singer's brooches now live in the Cartier Collection, and Maria costume designer Massimo Cantini Parrini worked with Cartier to obtain some of Callas' finest jewelry. According to Jolie, she wore the real designer pieces as a nod to Callas not just on the red carpet, but also on screen in the biopic.

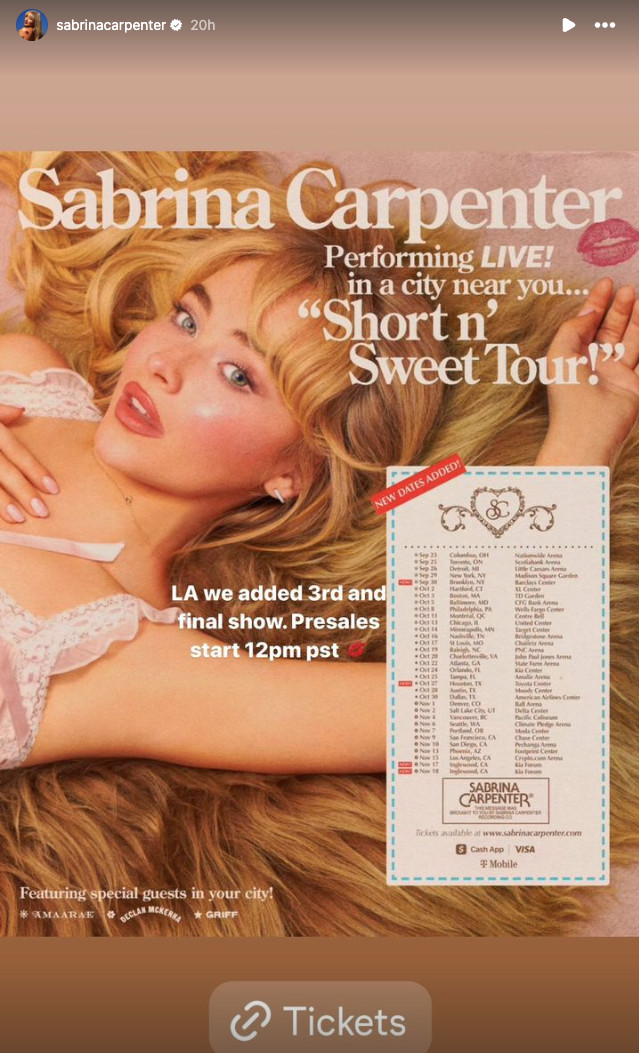

Her red carpet brooch was a 1972 Rose Ouvrante in the shape of a flower, that features diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, and rubies. The jewelry — which Jolie wears in the movie — also has a special mechanism that makes the flower petals open and close.

"I was also charmed at how it transformed from a closed flower that then blooms," Jolie told Vogue. "I like to think it made her smile. The little secret in the piece."

Earlier on Thursday, Jolie paired one of her own Atelier Jolie black dresses with a 1971 Panthère brooch, featuring the classic gold Cartier panthers with emeralds for eyes alongside a white chalcedony gemstone, the magazine reported. This brooch was also featured in Maria, Jolie added.

"You can imagine how special it was to wear a piece of jewelry that was hers," she said.

Jolie has previously been candid about how she felt connected to Callas — whose life is known as somewhat tragic — and fully submerged herself in the world of opera to understand her character. Earlier on Thursday, she spoke at a press conference alongside other cast and crew about how she related to Callas' story.

"Well, there's a lot I won't say in this room, that you probably know or assume," Jolie told the crowd with a laugh.

"I think the way I related to her may be a surprise — [it was] probably the part of her that's extremely soft and doesn’t have room in the world to be as soft as she truly was, and as emotionally open as she truly was," the Oscar winner said.

She added of Callas, "I share her vulnerability more than anything."

Based on true accounts about Callas, Maria will tell the "tumultuous, beautiful and tragic story of the life of the world's greatest opera singer, relived and reimagined during her final days in 1970s Paris," according to a press release.

Details about Callas' life have previously been explored in Lyndsy Spence's biography about the star Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas, which was excerpted in an April 2021 article from The Guardian.

The Venice Film Festival loves its movie stars, and Angelina Jolie was the toast of Italy on Thursday night. The actress wept during an eight-minute standing ovation at the Sala Grande Theatre at the world premiere of “Maria,” Pablo Larraín’s biographical drama about the Greek opera singer Maria Callas.

Jolie was similarly taken by the rapturous response, wiping away tears and at time turning her face away from the cheering as she was overcome by emotion. She hugged Larraín and the cast of the film, which is sure to be an Oscar contender, putting Jolie in the best actress race for the first time in 15 years. (She was nominated in 2009, for her her work in Clint Eastwood’s “The Changeling,” and won an Oscar for best supporting actress in 2000 for “Girl, Interrupted.”)

Netflix will release “Maria” later this year.

In Venice, the fandom for Jolie started a full 24 hours before the screening of “Maria.” A group of Italians camped out overnight on Wednesday with tents and umbrellas, enduring 90 degree temperatures for a front-row interaction with their idol at the carpet.

When Jolie arrived at the theater, she dutifully signed autographs and took selfies. She even met a fan with brittle bone disease who had been transported to the carpet on a bed, kneeling beside him as she greeted him amidst the flashing lightbulbs from the paparazzi.

Maria reunites Larraín and writer Steven Knight, whose last project “Spencer” bowed in Venice in 2021, and tells the “tumultuous, beautiful, and tragic story of the life of the world’s greatest opera singer, relived and re-imagined during her final days in 1970s Paris.”

“Maria” is the third in Larraín’s trilogy of films about iconic women, following “Spencer” and 2016’s “Jackie” about Jacqueline Kennedy in the aftermath of her husband JFK’s assassination. But “Maria” at time plays like a bookend to “Judy,” the 2019 biopic that won Renee Zellweger an Oscar for portraying a troubled Judy Garland, contending with the pitfalls of fame.

At a press conference earlier in the day, Jolie spoke about preparing to play the famous soprano Callas, which marked her first time singing in a role.

“Everybody here knows, I was terribly nervous,” she said of learning to sing opera. “I spent almost seven months training because when you work with Pablo you can’t do anything by half. He demands, in the most wonderful way, that you really do the work and you really learn and train.”

It’s been three years since Angelina Jolie appeared in a movie, though she’s been making a retreat from stardom for a lot longer than that, pulling back pieces of herself from the public sphere as well as from the persona she projects onscreen. Gone are the days of the blood-vial-wearing wild child or the bombshell whose chemistry with co-star Brad Pitt in Mr. and Mrs. Smith made their coupling up feel inevitable. As a celebrity, she’s stripped sex from her image entirely, emphasizing instead her identity as a filmmaker, a human-rights activist, and a mother of six. As an actor, she’s voiced a tiger in the Kung Fu Panda franchise as often as she’s actually appeared onscreen over the last decade, and in the live-action films she has taken on, her roles have been increasingly defined by her character’s aloof beauty and elegant suffering. I can’t begrudge Jolie her desire to armor up and put more layers between herself and a public that’s been ingesting the intimate details of her life since she was scarcely old enough to legally drink. But I also can’t deny that I’ve found this Madonna-martyr phase in her career less than compelling. At her best, Jolie is thrilling, a talent who’s capable of bursting into the frame and making you believe she’s about to devour the world whole. In her more recent roles, even when running headlong through a raging forest fire, she feels only half there.

That tendency holds true in Maria, the new film from Chilean director Pablo Larraín, in which Jolie plays legendary opera singer Maria Callas. The role is her most ambitious in ages, and yet it doesn’t feel like a reemergence so much as it does a project that’s been constructed around the strategically withholding presence she’s become. The part comes with all sorts of details that serve as the heralds of its legitimacy, like the fact that Jolie spent months in training to sing opera, her real voice blended with Callas’s famous one whenever her character performs. Despite that, there’s something bloodless about what Jolie actually does onscreen, a level of remove that makes it seem like she’s playing a woman who’s playing Maria Callas. Some aspect of that is intentional — Maria is the final part in a trilogy from Larraín that began with Natalie Portman as Jackie Onassis in Jackie and continued with Kristen Stewart as Princess Diana in Spencer, and while it’s the weakest of the three, it is, like the previous installments, as much about image-making as it is about the iconic woman at its center. Its Maria, living in Paris toward the end of her life, hasn’t sung onstage in years but still can’t stop performing — whether it’s burbling an aria in the kitchen for her housekeeper, Bruna (Alba Rohrwacher), or playing the diva for a TV journalist (Kodi Smit-McPhee) who’s actually a pill-induced hallucination.

All three of these Larraín films play coy with the idea of image as both power and a prison, acknowledging how absurdly elevated a problem that is to wrestle with, while at the same time trying to treat it with the seriousness its subjects demand. But Maria has the toughest time finding that balance and reconciling the imperiousness it wants from its subject with its insistence that she spent most of her life trying to please those around her. The film slips between the miniature productions that make up Maria’s day-to-day in 1977 and ones she did in the past onstage, but there’s nothing behind these displays, no fleshly substance to the character underneath the theatrical costumes and even more sumptuous everyday outfits. The purplish script, by Steven Knight, is written as though every other line were intended not to be spoken as part of a scene but to be highlighted in an eventual trailer. “What did you take?” demands Feruccio (Pierfrancesco Favino) — Maria’s butler and, alongside Bruna, other constant companion — when trying to monitor his mistress’s pill consumption. “I took liberties, all my life, and the world took liberties with me,” she answers. When Feruccio manages to arrange for Maria to see the doctor she’s been avoiding, that doctor tells her reassuringly that he “needs to have a conversation with you about life and death, about sanity and insanity.”

Is Maria insane? She’s definitely meant to be a mess, teetering out of the grasp of her doting domestic help, causing scenes at cafés, and imagining an interview with Smit-McPhee, who shares a name with her preferred brand of downers, when she isn’t trying to rediscover her voice with the help of a pianist (Stephen Ashfield) who might also be a figment. And yet, Maria remains so fastidious with its main character, as well as the actor playing her, unwilling to admit that there might be something as pleasurable as there is tragic about the spectacle of an opera star tearing apart her dressing room in search of a few last Quaaludes. Jolie looks incredible in the film, all angular cheekbones and brocade housecoats, divine in a cat flick eye and beehive in black-and-white flashbacks to her romance with Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer). Maria looks incredible, too, with cinematographer Edward Lachman giving ’70s Paris the exact look of a vintage postcard, and Larraín staging flights of fantasy that involve choirs turning up out of the crowds on the Place du Trocadero and orchestras sitting on the steps in the rain. But despite the obvious effort that went into the making of Maria, there’s so little life. For a movie built around a performance meant to be lauded for its bravery, there’s no sense of anything risked.

It’s the night before the premiere of Maria—the Pablo Larraín–directed Maria Callas biopic that is already the most talked-about film at this year’s Venice Film Festival—and its star, Angelina Jolie, is feeling reflective. “I met Pablo many years ago and told him how much I respected him as a filmmaker and hoped to work with him one day,” Jolie tells Vogue of how she decided to take on this once-in-a-lifetime role. “To be asked to play Maria was an honor and the most challenging role I have ever taken on—above all, because I do feel so strongly about her as an artist and a woman that I worried about not doing her justice.”

On that, Jolie need not worry. With Maria, she delivers arguably the greatest performance in her already remarkable career, fully embodying the legendary Greek opera singer in her 1970s twilight years in Paris: her striking kohl-rimmed eyes, her fraying voice, and her tempestuous moods. To achieve it, Jolie dedicated herself to an intensive training process so that she wasn’t just delivering a portrait of Callas but instead became her, somehow. “Pablo expected me to work very hard, and he expected me to sing,” she says. “I went into classes for six or seven months to learn to really sing, to take Italian classes, to understand and study opera, to immerse [myself in it] completely and do the work. For Maria, there was no other way.” However grueling that journey may have been, it was a process that left Jolie feeling creatively fulfilled. “I am deeply grateful to Pablo for having faith in me to do this,” she adds.

Yet there was another equally important element of Callas’s life that Jolie was fully committed to realizing on screen: her style. For Callas, fashion wasn’t just the clothes she dressed in every day but an armor that allowed her to step out into an at times hostile world. As a result, Callas became a couture client to some of the greatest designers of her day, including the Italian couturier Biki, Christian Dior, and Yves Saint Laurent. (The opera star is still inspiring designers: Just look to Erdem’s fall 2024 collection, which featured gestural swoops of paint across floral gowns mimicking the designs of Salvatore Fiume’s sets in her 1953 La Scala production of Medea, accompanied by the only surviving recording of Callas speaking in Greek.)

While Jolie worked closely with Maria’s costume designer Massimo Cantini Parrini on the outfits that would inform her performance, the extra sparkle that helped her embody Callas came via Cartier. Throughout her lifetime, the singer amassed an extensive collection of gems—but few were as prized as the pieces she acquired from the legendary French fine-jewelry house. One such piece is a figurative Panthère brooch made in 1971, featuring one of Cartier’s signature gold panthers (complete with emeralds for eyes) sitting atop a carved white chalcedony gemstone.

It turns out Callas’s actual brooch is now in the Cartier Collection and was worn by Jolie both in the film and at the press conference for Maria in Venice today, affixed to her black Atelier Jolie column dress. “You can imagine how special it was to wear a piece of jewelry that was hers,” Jolie tells me of both wearing the brooch during the film’s production and stepping onto the global stage to promote Maria with a little bit of Callas on her chest.

Elsewhere in the film, Jolie also wears a Rose Ouvrante 1972 flower brooch, featuring diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, and rubies, with a special mechanism that allows the petals to be opened and closed. Tonight, Jolie wore the piece for the evening premiere of Maria with a Tamara Ralph chiffon gown and faux fur stole. “I was also charmed at how it transformed from a closed flower that then blooms,” Jolie adds. “I like to think it made her smile. The little secret in the piece.”

For Cartier, it feels like a full-circle moment too. “Like so many other important women of the time, Maria Callas chose Cartier for jewelry that reflected her personality,” says Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s image, style, and heritage director, before going on to quote the iconic Mexican actor María Félix: “Cartier has always been known as the jeweler of the aristocracy of blood, but also of talent.”

Ahead of debuting her Tamara Ralph look on the red carpet at the Palazzo del Cinema tonight, Jolie noted we should expect the unexpected when it comes to her Venice wardrobe. “I chose not to copy [Maria’s] looks because they are hers, and her Venice carpets were stunning, so I gave a little nod to her—in a different way,” she says, before adding: “But I made sure to wear something ladylike in her honor.” (Earlier today, Jolie also wore a Saint Laurent dress with Grecian-style sleeves that served as a subtle homage to Callas.)

Still, having worked on this project for nearly two years, how does it feel now it’s finally out in the world? And ultimately, what does Jolie hope the audience will take from this movie? “I just hope this film helps Maria to be more understood and respected.” If Jolie’s performance is anything to go by, it will do all that and more.