Experts warn an Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear sites could push Tehran closer to developing a nuclear weapon, potentially backfiring. Diplomacy is seen as a safer path, but any military action risks wider regional conflict.

Could Israel destroy Iran’s nuclear program if it wanted to? And if Israel chose to attack Iranian nuclear facilities, would it be effective?

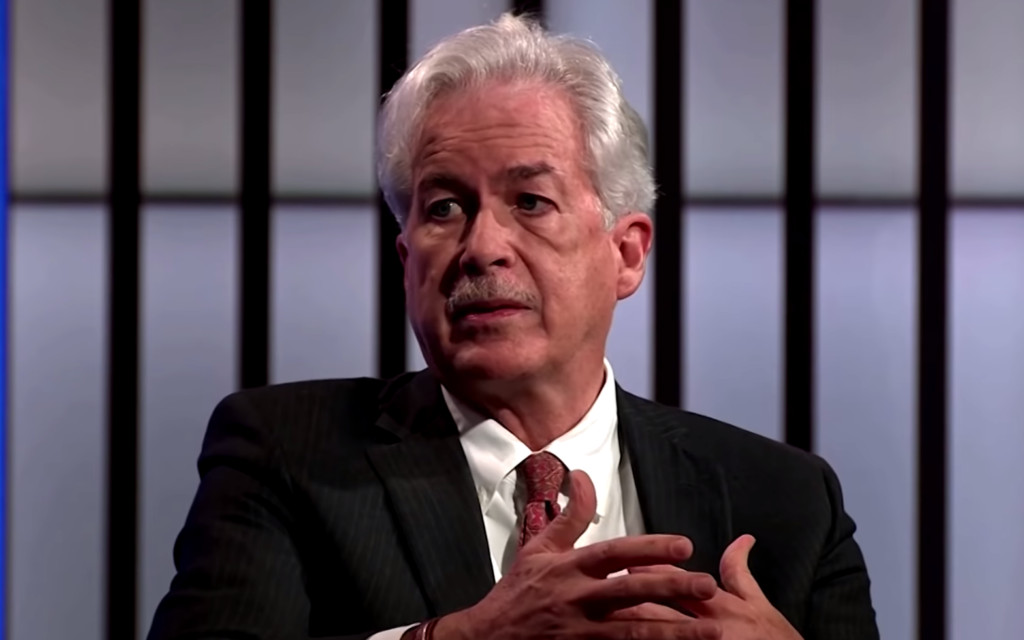

Several experts say the outcome may not be what the Israeli public hopes for. An attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities could strengthen Iran’s resolve to acquire a nuclear weapon rather than eliminate its capability, says James Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

They play, you play. You try not to cross a line. When the line is crossed, it’s total war. We have to consider what the repercussions would be.

“They play, you play,” said Tel Aviv University’s Prof. Eyal Zisser. “You try not to cross a line. When the line is crossed, it’s total war. We have to consider what the repercussions would be.”

Iran does not yet have a nuclear weapon, but it has operated a civilian atomic energy program for over five decades. Analysts believe Iran could produce enough enriched uranium and the necessary components to build a nuclear weapon in a relatively short time. However, this doesn’t mean Israel can—or should—target Iran’s nuclear program the way it did with Iraq’s or Syria’s.

Iran’s nuclear program relies on centrifuges rather than nuclear reactors, which are used to enrich uranium, James Acton explained to The Media Line. These are the same types of centrifuges that fuel power reactors. Centrifuges are small, about 20 to 30 centimeters in diameter, and one to two meters tall. Acton said Iran has at least a few thousand of these at two main sites: Natanz and Fordow.

This situation is very different from Israel’s attacks on Iraq’s Osirak reactor in 1981 and Syria’s reactor in 2007. In those cases, the nuclear weapons programs were concentrated in a single, large facility centered around one reactor, which had required significant resources and investment to build. As a result, destroying those reactors effectively dismantled the entire nuclear program. The Osirak strike set Iraq’s nuclear ambitions back by at least a decade, while Syria, due to its ongoing civil war, was never able to rebuild.

Acton explained that the program could be rebuilt quickly with centrifuges because they “are very small and can be manufactured quickly and placed almost anywhere.” Even if Israel were to destroy some or all of Natanz or Fordow, “Iran is almost certainly going to reconstruct centrifuge facilities.”

Acton explained that Iran would likely respond by relocating any new facilities deeper underground or even hiding centrifuge operations in regular, unmarked industrial buildings in plain sight. As a result, Israel would have to continuously track and detect these sites, potentially launching new strikes every year or two.

While an Israeli strike can dent its capabilities in the short term, it can’t remove those capabilities in the long term.

“While an Israeli strike can dent its capabilities in the short term, it can’t remove those capabilities in the long term,” Acton said.

Regarding the two known facilities—though there may be additional clandestine sites—Natanz consists of a large underground facility housing around 50,000 centrifuges and a smaller facility at ground level. Acton estimated that the underground facility is no more than 10 meters deep. In contrast, the Fordow facility is buried within a mountain, likely 60 to 80 meters underground. Given this, there is considerable evidence suggesting that Israel lacks the capability to destroy Fordow.

Acton explained that Israel would need the US-developed Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) for such a mission. However, even if the US were willing to provide Israel with the weapon, there would only be a practical way to deliver it to Iran with US assistance. The MOP, over 20 feet long, is much larger than other bunker busters and penetrates deeper than any conventional alternative.

Professor Hooshang Amirahmadi, president of the American Iranian Council and a professor at Rutgers University, suggested an alternative: using an Azerbaijani airbase near western Iran to get closer to the target. However, despite Israel’s strong ties with Azerbaijan, the country has never publicly agreed to such a plan, and Amirahmadi doubts it would allow Israel to do so.

As such, unless Israel can carry out a cyberattack or find another method to disrupt Fordow, it will likely have to hold off without full US support.

Even if attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities were possible, it might not be the best course of action, according to Acton. Although US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in June that Iran could produce enough fissile material for a weapon in “one or two weeks,” the country would still need to take additional steps to turn this material into a functional weapon.

Acton explained that he believes Iran is aiming to have the capability to build a nuclear weapon quickly but has not yet decided to actually produce one.

“An Israeli strike makes it much, much more likely that it will make the decision to do so,” Acton told The Media Line. He added that if Iran acquires a nuclear weapon, it would feel significantly more emboldened.

One can imagine an Iran more willing to strike Israel and target civilians with ballistic missiles, potentially in larger numbers. I think a nuclear-armed Iran is a pretty bad prospect for Israel.

“One can imagine an Iran more willing to strike Israel and target civilians with ballistic missiles, potentially in larger numbers,” and using its proxies more openly,” he said. “I think a nuclear-armed Iran is a pretty bad prospect for Israel.”

Both Acton and Amirahmadi agreed that diplomacy is a better option and likely the one the US would prefer over a risky military response. Israeli action without US support could strain the relationship between the two countries.

“The US has already said it does not like the idea of Israel attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities because it thinks it can stop enrichment in Iran through negotiations, just like they did last time,” Amirahmadi said.

In 2015, Iran signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. However, the US unilaterally withdrew from the agreement in 2018. Acton believes another deal could be reached—perhaps not as sophisticated as the original JCPOA, but one that could still verifiably keep Iran short of developing a nuclear bomb.

Acton noted that the US would likely need to lead such an initiative, though another country could publicly take the lead while the US provides sanctions relief as part of the deal. He also expressed concern that diplomacy might be abandoned altogether if former President Donald Trump returns to office. On the other hand, he is “not optimistic” that Vice President Kamala Harris, if elected, would prioritize such a deal, although she is “temperamentally much more inclined to reach an agreement. ”

Alternatively, Israel could choose to target Iran’s oil infrastructure, which might have an even greater impact, Amirahmadi told The Media Line.

“What Iran is really concerned about is not that Israel will hit its nuclear program,” Amirahmadi explained. Instead, he said a strike on the country’s oil supply and shipping infrastructure “will certainly escalate this conflict” and could even lead to regime change because it would “stop Iran from functioning economically.” However, he cautioned that if such a strike were to happen, “you could not control Iran because Iran will feel very lost.”

Oil is Iran’s primary export. Attacking its oil export facilities on the Persian Gulf coast “would be something Iran could not tolerate, and Iran would respond in a way no one could imagine. That would be a game of life and death.”

Acton added that such a strike could also have immediate consequences for Western countries. Even though Iran supplies only a limited amount of oil compared to other suppliers, it’s still significant. If global oil supplies are disrupted, oil prices are likely to rise.

But doesn’t Israel want regime change in Iran more than anything else?

Amirahmadi warned that it won’t be as simple as some might hope. Before the regime falls, it would likely retaliate, and “it could be a mess.”

Iran would probably use whatever technology it has not yet shown the world, a technology it’s hiding. I don’t know what it is, but they always claim to have things that could make the world tremble.

“Iran would probably use whatever technology it has not yet shown the world, a technology it’s hiding. I don’t know what it is, but they always claim to have things that could make the world tremble,” Amirahmadi said.

He also predicted that the situation would “certainly spill over to other places.”

More realistically, Amirahmadi suggested, Israel is likely to target Iran’s military infrastructure, particularly that of the IRGC. Reports indicate that Israel has created a short list of targets and shared it with the US, though the list remains undisclosed. A report by The Washington Post this week revealed that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu assured US President Joe Biden that Israel would avoid attacking Iran’s energy or nuclear sites. However, Netanyahu emphasized, “We listen to the opinions of the American administration, but we will make our final decisions based on Israel’s national interests.”

Last week, Defense Minister Yoav Gallant hinted at Israel’s impending response to Iran’s massive strike on October 1, saying it would far surpass the original attack. He did not provide specifics but added, “The Iranian attack was aggressive but inaccurate. In contrast, our response will be deadly, pinpoint accurate, and, most importantly, surprising—they will not know what happened or how it happened. They will just see the results.”

When will there be more answers? It’s likely only when Israel sets the rogue regime ablaze.

“No, we do not see evidence today that the supreme leader has reversed the decision that he took at the end of 2003 to suspend the weaponization program,” Burns told the Cipher Brief security conference, according to NBC News.

In 2003, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei issued a fatwa prohibiting the development of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction. His predecessor, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, also rejected the idea of starting a WMD program while facing chemical attacks from a U.S.-backed Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s.

Burns said that if Iran did move to make a nuclear weapon, U.S. intelligence would likely be aware of the decision. “I think we are reasonably confident that–working with our friends and allies–we will be able to see it relatively early on,” he said.

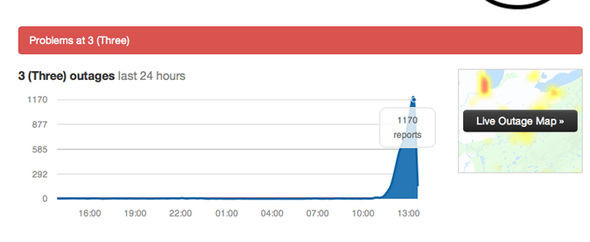

The CIA chief noted that Iran has increased uranium enrichment levels since the U.S. withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the JCPOA, in 2018. Iran is enriching some uranium at 60%, which is still below the 90% needed for weapons-grade.

Iran increased uranium enrichment to 60% in 2021 following an Israeli sabotage attack on Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility, which was timed to sabotage indirect negotiations between Washington and Tehran..

Burns claimed Iran would only need one week to “produce one bomb’s worth of weapons-grade material,” but the NBC report noted most experts say it would take at least one year to build an actual nuclear warhead.