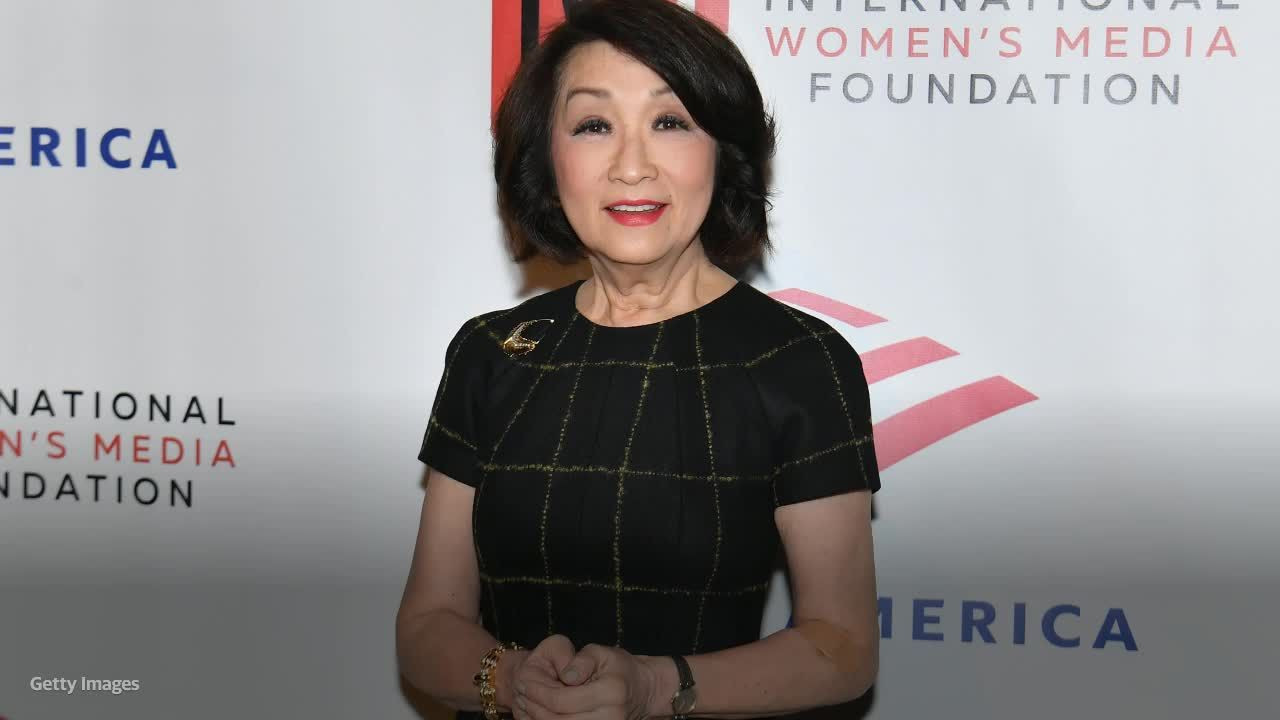

Veteran TV news anchor Connie Chung jokes that part of her success can be attributed to booze and bawdy humor. That's because when she was first starting out, she was often the only woman among the all-male press corps.

On the road covering the 1972 presidential campaign, Chung tended to retreat to her hotel room at night. She thought she was being responsible by prepping for the next day— then she noticed the male reporters were getting scoops that she was missing.

"It suddenly dawned on me they were saucing up the campaign manager and everyone who worked for the candidate, and letting them spill the beans," Chung says.

Chung began to go down to the bar at night, where, she says, drinking and jokes helped her to break into the press corps “boys club.”

"Therein lies a great way to learn how to be a reporter," she says. "I don't recommend it by any means. But at the time, I just had to find a way."

In her new memoir, Connie, Chung opens up about the decades she spent covering the news, her marriage to tabloid talk-show host Maury Povich and the prominent figures who acted inappropriately with her — including President Jimmy Carter, who, she says, pressed his knee against hers suggestively at a black-tie dinner.

In 1993, when Chung was named co-anchor of CBS Evening News, she became the first Asian American — and second woman — to have the position. She says it was “pretty clear” that veteran newsman Dan Rather didn't want her there.

“I don't blame him totally, because he had owned Walter Cronkite's chair for many years and had to move over a few inches to make room for me,” she says. “And I do believe that had I been another man, had I been an animal, had I been a plant … he would not have wanted anyone to share that seat with him.”

Throughout her career, Chung was often one of the few Asian American newscasters on television. In 2020, Chung realized the impact she'd had on the community when a writer named Connie Wong reached out, telling her about a generation of immigrants who had named their baby girls after her.

“There were these ... babies who were actually named ‘Connie Chung’ and then their last name,” Chung says. “Honestly, I can't really embrace how gargantuan it is. It is profound.”

Covering the O.J. Simpson Trial – Even Though She Didn't Want To

“The men could not be pushed into that direction. CBS News, Dan Rather, who was my co-anchor, wouldn't touch it. And 60 Minutes, it was all men at the time and they wouldn't touch it. So they wanted nothing to do with O.J. Simpson. And frankly, I didn't either. But the management would come to me and say, “Barbara Walters is getting X, Diane Sawyer is getting Y and Katie Couric is getting Z. You have to do this for the team.” I said, “I don't want to, I don't see the value in it. It's tabloid.”

“I have a lot of regrets, but that is one of the biggest ones, of being the good girl, … being told what to do. Resisting, but never being able to put my foot down and say, “I am not doing it. Go find somebody else.”

Learning How to Stake Out a Story From Barbara Walters

Chung reveals she learned a lot from veteran journalist Barbara Walters, particularly about how to aggressively pursue a story.

“She picked up the phone herself. She wrote a letter. She faxed. She called. She nudged. She would say, “Let’s have lunch.” And I would call it, “Being Barbara’d.’”

“Barbara and I had a lot in common. She was clearly the pioneer and paved our way. But she was the breadwinner in her family because her father's nightclubs tanked and she had to take care of her mother and her father, support her mother and her father and her disabled sister. I was the breadwinner in my family as well for my mother and father. I supported them till the day they died. From about 25 on, I was their parent. We both co-anchored with someone who despised us, a man. We were both fired after two years. We both adopted a child. We both married nice Jewish boys — although I think Barbara married maybe two or three. But I admired Barbara because she paved our way.”

Her Marriage to Maury Povich

Chung also delves into her long marriage to talk show host Maury Povich, a relationship she describes as “perfect” despite their very different personalities.

“I'm still wondering how come we are a perfect match, because we are so different. But the public personas belie what is really behind our door. ... He's a very down-to-earth, realistic guy. What belies his public persona is that he is very much a voracious reader. He's a political buff. He's a history buff. He could run circles around these pseudo-intellectuals who do interviews with important people. And I always say that to him: “Why don't you do a serious talk show? ...You're so smart and people would know how smart you are.” And he says, “As long as you know that, I'm fine.” And I thought, my goodness! What a guy.”

The Anti-Social Couple

Chung and Povich are famously homebodies, leading a quiet and reclusive lifestyle.

“Maury and I stay home all the time. We’re so boring. If someone asks us to go have dinner, we have to think about it for a few months. … I'm the one who's even more anti-social in the sense that. I want to wash my face and take off my makeup and look scary. And I don't want anybody else seeing me looking scary.”

The State of TV News Today

Chung expresses her disappointment with the current state of TV news, particularly the lack of in-depth interviewing and investigative journalism.

“When I see [a bad] interview on television, I want to throw my shoe at it if somebody isn't asking the question, the next question that I would ask. ... I miss that — the interviews and being able to dig deeper, but I also miss the joy of going after a story that's worthy. And I know it sounds really old-fashioned, but if I can change a government wrong or a change an attitude regarding social ills or whatever, something like that, I think it's so gratifying.”

Why She Wrote Her Memoir

Chung's decision to write her memoir was inspired by a letter she discovered from her father, encouraging her to tell their family's story.

“I came across a letter from my father, and he had written it when I had already begun in the news business. … My parents were born in 1909 [and] in 1911, in old China, pre-communist China. They grew up with very traditional parents. My mother's feet were bound. Their marriage was arranged when she was only 12 and he was 14. They were married at 17 and 19. ... They had 10 — if you can believe it — children. I was the 10th, the only one born in the United States. They had nine children in China, five of whom died as infants. Three of those infants who died were boys. ...

So they raised five very ballsy women. And I have to say that they all could have been CEOs or had different lives had they grown up in a different era. But ... my father gave me this mission. He said, “Maybe you can carry on the name Chung. Tell everybody how we came to the United States,” meaning him and my four older sisters and my mother.”

Chung’s Account of Sexual Abuse

Chung’s memoir also touches on the painful topic of sexual abuse at the hands of a trusted family doctor. She reveals that she was sexually assaulted during her first gynecological exam by the same doctor who had delivered her.

“What made this monster even more reprehensible was that he was the very doctor who had delivered me on August 20, 1946,” Chung wrote in “Connie: A Memoir,” according to an excerpt shared with Us Weekly.

Chung, 78, wrote that she was in college at the time of the incident and had booked an appointment with the gynecologist to obtain birth control. She detailed how the doctor, who has since died, allegedly massaged her genitals and coached her through the assault. Chung wrote that “for the first time in my life, I had an orgasm,” and that her doctor had leaned over and kissed her on the lips after the interaction.

“I did not say a word. I could not even look at him,” she wrote.

Chung’s account of the abuse in her memoir echoes lines from a 2018 letter she penned to Christine Blasey Ford amid Blasey Ford’s allegations of sexual assault against then-Supreme Court nominee Brett M. Kavanaugh. In the letter, published in the Washington Post in October 2018, Chung said the abuse occurred during the 1960s.

“I did not report [the doctor] to authorities. It never crossed my mind to protect other women,” she wrote in the letter. “Please understand, I was actually embarrassed about my sexual naivete. I was in my 20s and knew nothing about sex. All I wanted to do was bury the incident in my mind and protect my family.”

Dan Rather's “Inherent Bias”

Chung — the first Asian American woman to anchor a major network news broadcast — said Rather was condescending from the start after CBS brass paired them in 1993 as his ratings slumped.

“I’ll cover the stories out there in the field, and you read the teleprompter,” Chung quotes him as telling her in her memoir, Connie, which was released Tuesday.

He also told the trailblazing journalist, who had interviewed world leaders and US lawmakers as host of the Sunday talk show Face the Nation, that she would have to “start reading the newspaper,” Chung said.

During their tumultuous two years together on the CBS Evening News, Rather was “wound tight and had no sense of humor,” with “an inherent bias regarding women,” she writes.

“My guess is that even if they put a dog, a cat or a plant” as his co-anchor, “it wouldn’t have made any difference,” added Chung, who is married to former talk show host Maury Povich.

“I just happened to be the recipient of, uh, his fertilizer that was being sprayed all over me.”

Rather led a whisper campaign among TV critics and journalism colleagues to smear Chung’s name — saying her journalism abilities weren’t up to par, she wrote.

Chung, 78, cited an earlier memoir by correspondent Bernard Goldberg in which Rather “spent hours and hours on the phone with TV writers, blasting Connie Chung as a second-rate journalist” during her coverage of the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995.

Rather was on vacation at the time and seethed to the The New York Times that being on the sidelines as she reported from the scene “was like trying to swallow barbed-wire-wrapped ball bearings,” Chung wrote.

Shortly after the terror attack, Rather gave CBS president Peter Lund an ultimatum and Chung was ousted soon after, she claimed.

Rather denied having anything to do with her exit.

“Nobody has heard a critical comment from me about Connie” and her removal “came as a surprise to us,” he told the Washington Post at the time.

The Post reached out to Rather for comment.

Chung — whose decades-long career also included stops at ABC, CNN and MSNBC — claimed Rather’s alleged sexist attitude toward female journalists was rampant throughout the industry.

“Many men in television news, especially those who became anchormen, contracted a disease: big-shot-itis,” Chung wrote.

“It was characterized by a swelling of the head, an inability to stop talking, self-aggrandizing behavior, narcissistic tendencies, unrelenting hubris, delusions of grandeur and fantasies of sexual prowess.”

Chung said she spent much of her career working with white men, or in rooms surrounded by them.

Sexism followed her throughout her career and critics were eager to point out any mistakes.

The B-tchgate Scandal

A 1995 interview with Newt Gingrich’s mother — whose son was then the new House speaker — turned sour thanks to a network decision, Chung wrote in her memoir.

During the interview, Gingrich’s mother told Chung that she could not say what her son thought about then-first lady Hillary Clinton. Chung told her to whisper the answer in her ear.

Gingrich’s mother whispered that her son had called Clinton a b-tch, and Chung’s mic picked it up.

CBS aired that whisper as a standalone clip — which made it seem like Chung had tricked Gingrich’s mother and sparked debates over whether Chung should have left the quote off the record.

The scandal became known as “B-tchgate” throughout the television industry. Chung said she wished she had insisted CBS back her up then, but she did not.

She dealt with sexual harassment from colleagues and subjects throughout her career.

At 25, she was assigned to cover the presidential campaign of Sen. George McGovern, who tried to kiss her in a dark hallway, she told USA Today.

Former President Jimmy Carter once pressed his leg against hers at a dinner “and then he looked at me and smiled,” she told USA Today.

Chung said she had to develop “armor” to deal with her sexist colleagues.

“I decided I’d be a guy,” she told the Today show. “I would have bravado, I’d have moxie, I had a bad, sassy mouth.”

Maury Povich and Connie Chung Reflect on Their Careers at FOX 5 DC

Chung and Povich recently returned to their old stomping grounds at FOX 5 DC for a virtual homecoming on “The Final 5 with Jim Lokay.” The duo reflected on their careers, their work at FOX 5, and their time in the D.C. region.

Chung, who grew up in the D.C. area as the youngest of 10, shared memories of her early days at the station as a “copy person,” although when a writing job opened up, she knew she had to fight for the opportunity. “I barged into the newsroom,” she recalled humorously. “Today, I’d probably be arrested at the door.”

Povich, also a local product, said many people in the FOX 5 newsroom didn't know much about Chung in her early days out of the University of Maryland, but when it was evident she was angling for a better position, she took matters into her own hands.

“Mike Buchanan, the news director at the time, told her she couldn’t take on a weekend writing job because she was his assistant,” Povich said. “But he gave in and told her to replace herself, so she went across the street to the nearby American Security Bank on Wisconsin Avenue, found a bank teller, and brought her back into the newsroom.

“I asked her, ‘Do you want to be in TV? Do you want to be a star?’ And that’s how I got my first job,” added Chung, who eventually became an on-air reporter, before moving on to make history as the first Asian American and second woman to anchor a major network news broadcast during her long, illustrious career across CBS, NBC, ABC, and CNN.

Povich, meanwhile, was originally a sports anchor but eventually became a fixture on WTTG.

“I was working seven days a week for 10 years,” Povich said, recalling his roles hosting Panorama and anchoring the weekend news.

Panorama, a groundbreaking midday talk show created by station manager Bob Bennett in 1967, was Washington’s answer to NBC's Today.

“It was an amazing stroke of genius by Bob,” said Povich. “There wasn’t anything like it—long before CNN and cable news—and it became a staple for the White House, Capitol Hill, and government offices.”

“Everybody was watching because it was the only show in town, and we got all the big interviews,” he said.

Povich hosted Panorama for 10 years, left for several TV jobs across the country, then returned to WTTG for another three years in the 1980s before making a splash on the national scene with A Current Affair.

The conversation shifted to Povich and Chung’s personal relationship, which also blossomed at FOX 5. Lokay noted that their careers eventually took them to Los Angeles, where they briefly worked together on-air. “He was the only person I knew when I got there,” Chung recalled.

Povich added, “but our relationship didn’t last long on air—only because I was the last person hired by a general manager who got fired, and the new GM fired me next!”

While their professional relationship in Los Angeles was short-lived, their marriage has stood the test of time. Povich humorously quipped, “She took pity on me, and that's how we’ve lasted.”

Aside from a show the two co-hosted for MSNBC in the late 2000s, Chung has enjoyed retirement, but she learned that putting her stories to paper was a different challenge.

In her new book, Connie: A Memoir, Chung made a candid reflection on her storied career in television. “Writing it was a horrible experience,” Chung admitted. “The first draft I turned in was what my editor called a ‘shitty first draft,’ and it was. I needed help because I was just giving the facts.”

Her editor encouraged her to focus on feelings, something Chung found difficult as a seasoned journalist. “Reporters aren’t supposed to feel,” she laughed. “But in a memoir, you have to tell how you felt. It was really torturous to write down how I felt, but I finally got it done.”

Povich, who read drafts along the way, offered feedback like, “You can’t say that!”—a dynamic that added some levity to the writing process. Ultimately, one of their friends offered high praise, telling them, “I was on the train reading the book, and it felt like I was talking to Connie for two hours.”

For Chung, the goal was clear. “I didn’t want to sound like I was crying in my soup. I just wanted to tell what happened and how I felt—without ever going ‘woe is me.’”

Lokay asked Chung about the challenges she faced as a woman in a male-dominated industry. “Every day there was sexism and racism,” she said. “But I dealt with it by being ‘one of the guys.’ I had all the bravado, moxie, and toughness to match them.” With her signature humor, she added, “I had a potty mouth, too. I still do!”

Chung’s Connie: A Memoir dives deeper into these stories and much more, offering a personal look at the barriers she broke and the lessons she learned along the way.