Kobad Bankwala, 68, and his wife Heidi fought for years to get help for their son, Darian, who suffered from a number of conditions including autistic spectrum disorder, depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms, and learning disability. He was an inpatient under the care of Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust (EPUT) between February to June 2020 and was sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

Darian was later downgraded to informal patient status, meaning he was to be nursed on general observation with open leave, despite having expressed the intention to kill himself.

He was discharged from The Linden Centre, in Chelmsford, on 7 July 2020 against his parents’ wishes. Darian was assessed at home by NHS staff on 9 October and 13 November that year but, despite his parents’ concerns over their son’s “very worrying behaviour”, he was not admitted as an inpatient again. Darian, the youngest of five brothers, took his own life on 27 December 2020 at the age of 22.

His parents, Kobad and Heidi, applied for Core Participant status – meaning they would have rights including being able to suggest lines of questioning via council – but were turned down by Inquiry Chair Baroness Lampard.

Mr Bankwala told i: “I told the Baroness that she needed to meet me to discuss my son’s complex case, but we were ignored. She is a barrister and knows how to navigate the system: she was on the Jimmy Savile Inquiry. We feel she has ambushed us because we were only told things at the last minute and, along with others, simply didn’t have the time to respond adequately before the inquiry starts.”

Darian received a home visit from a consultant psychiatrist, on 18 September 2020, who decided that he did not satisfy the criteria for detention as an inpatient. The inquiry told the Bankwalas that although Darian had previously been an inpatient, he had been discharged five months before he died meaning his death “would not fall within the scope” of the inquiry.

The inquest into his death concluded that Darian’s discharge “should have been managed in a more professional way” among multiple failings. The court heard he was advised by a senior medical practitioner to self-treat at home, with “little to no professional guidance” as to what this treatment would involve.

Mr Bankwala said: “We were trying to get Darian admitted all the time, but they just wanted to get rid of him, completely. I have a letter from the hospital apologising, saying his release from hospital was ‘unsafe’ and his care in the community was ‘sub-standard’. So we were devastated to be told we didn’t warrant Core Participant status, angry, upset.”

Bereaved parents at the heart of The Lampard Inquiry have hit out at being asked their financial status before giving their impact statements.

Inquiry chairs are obliged to ascertain how many assets and how much monthly disposable income core participants have before deciding whether a payment towards their legal representation should be awarded in the public interest, under the terms of The Inquiries Act 2005. Inquiry core participants have been asked if they have disposable income of less than £3,200 each month and whether they have assets exceeding £60,000.

Julia Caro, whose son Chris Nota, died aged 19 in 2020 while under the care of Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust, told i: “Some people say they haven’t been asked this, but it is strange. They shoot you and then they want you to pay for the bullet. What if we did or did not have the minimum assets needed to pay for legal aid, but then chose not to or could not? Would we have an inquiry with no lawyers on one side? It’s just nonsense.

“Our lawyers have been funded as late as physically possible so that they’re on the back foot. Impossible deadlines were given over witness statements. It didn’t have to be that way.”

Melanie Leahy has fought for a public inquiry for more than a decade following the death of her son Matthew, aged 20, at The Linden Centre in 2012.

She said: “Why are we being means tested? Who made this a policy and why are we being penalised? The communications have been poor. We’ve been asked by the inquiry through our solicitors who we’re bringing with us, but we don’t even know what day of the week we’re coming or what time, so how we can we possibly do that when we don’t know when we’re being called?

“Some people have loved ones at home they need to find care for, others are working and need to take time off. We all have a distinct lack of confidence in how it’s been run already, before it even starts.”

Priya Singh, partner at Hodge Jones & Allen that represents more than 120 victims and families, said: “Our families are being asked about their income and savings to see if they are eligible for their legal costs to be covered by the Government. The families are stunned that they are in the position that they have to provide this information. In their eyes, why did the minister not dispense of means testing? Did the chair propose the dispensing of means testing to the minister? If not, why not?

“Why are the families put in the very stressful situation where they are told that if the relevant criteria are not met, they may have to cover legal costs for an inquiry which is looking at the failures by the state which has resulted in the death of their loved ones?”

A spokeswoman for the inquiry said costs relating to legal representation are a matter for the Government. However, health officials said while ministers determine the parameters for legal costs to be awarded by statutory inquiries, individual decisions about legal costs for core participants are made by the inquiry chair, independent of government.

The inquiry will sit for three days from Monday and hear opening statements from the chair, lawyers representing the families and Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust. It will hear impact evidence from families and friends of patients who died, or evidence from former patients of the impact on their lives, between 16-25 September.

Health and Social Care Secretary Wes Streeting told i: “My thoughts are with all those affected, including the families and loved ones of those who tragically died. This is incredibly sad, with loss and suffering on a large scale. As part of this, I will be meeting the families shortly to hear directly of their experiences and to reassure them that we take this issue extremely seriously.

“We remain committed to assisting the inquiry and will work with partners to transform mental health care as we fix our broken NHS.”

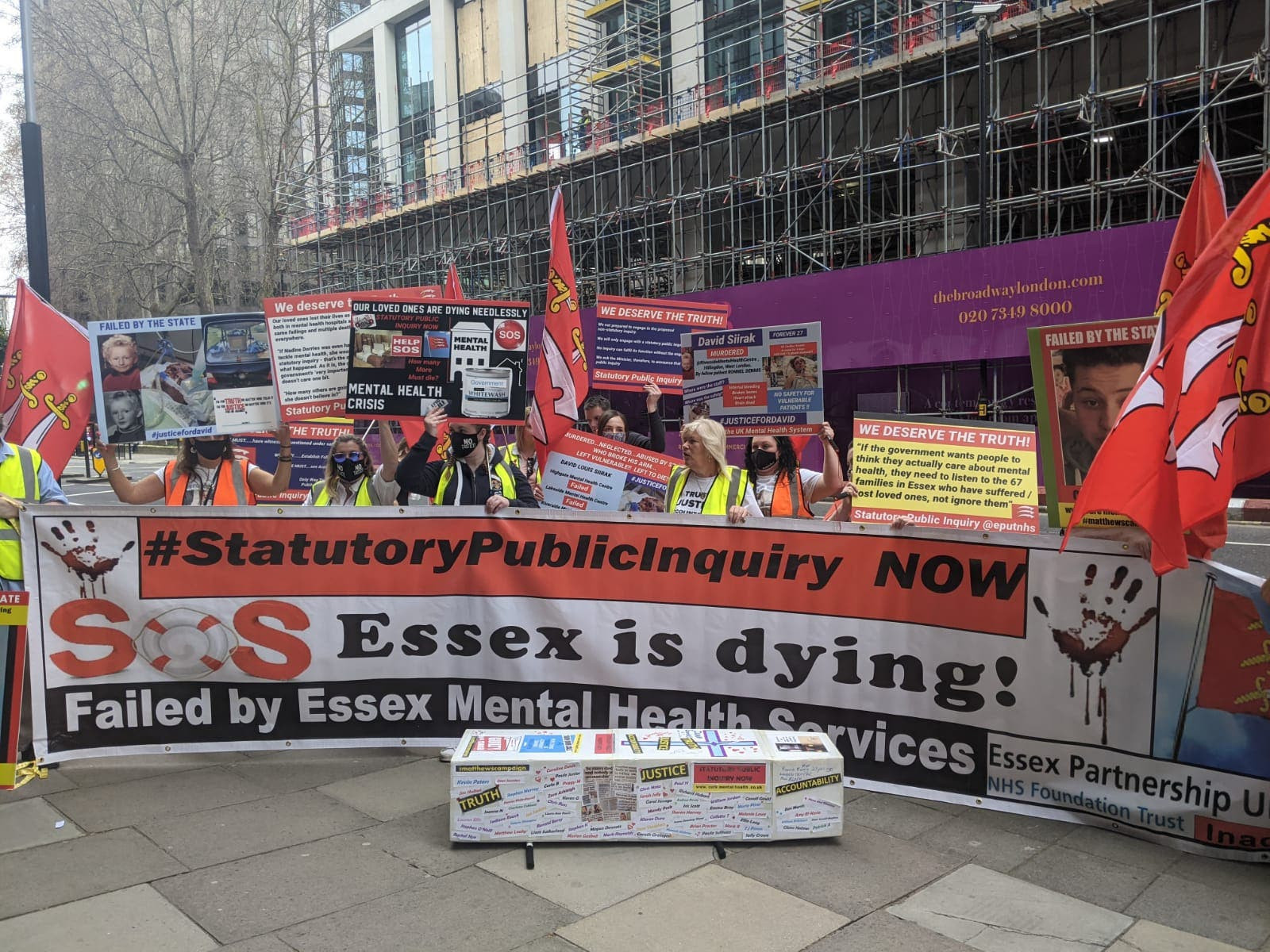

The first inquiry into mental health – the Essex Mental Health Independent Inquiry – was set up in January 2021 and chaired by Dr Geraldine Strathdee. She then called for the extra powers after just 11 staff members out of 14,000 agreed to give evidence.

In June 2023, Health Secretary Steve Barclay agreed to give the inquiry statutory powers, meaning witnesses were legally compelled to give evidence. Baroness Lampard was announced as the new chair of the converted inquiry last September.

Priya Singh, partner at Hodge Jones & Allen which is representing 126 affected families, 56 of whom have received core participant status, told i: “With regards to those families who have been refused core participant status, they have also fought tooth and nail to bring this inquiry to fruition. They feel like they have been abandoned and betrayed.

“Without their relentless campaigning there simply wouldn’t be an inquiry, an inquiry that is paramount to saving future lives and ascertaining how a care service has seen over 2,000 unexplained deaths. In some cases, we see no legal reason as to why they have not been granted this core participant status.

“We urge the inquiry to reconsider their decision. Every death, act of abuse and harm matters and should form part of this investigation so the right recommendations can be implemented to end the systemic failings.”

A spokeswomen for the inquiry said: “The Lampard Inquiry encourages participation from anyone who is personally affected by the issues it is investigating. Decisions on core participant (CP) status are ongoing, there are currently 75 designated CPs but this number is likely to change as the decisions are made on an ongoing basis.

“It is not necessary to be a CP to engage meaningfully with the inquiry. Personal accounts and experiences shared by those who are not CPs are of no less value in the eyes of the inquiry, than those provided by persons who are CPs. Being a core participant does not mean that a person’s evidence is any more important or given any greater weight. The inquiry values listening to a range of different experiences.”

All rights reserved. © 2024 Associated Newspapers Limited.