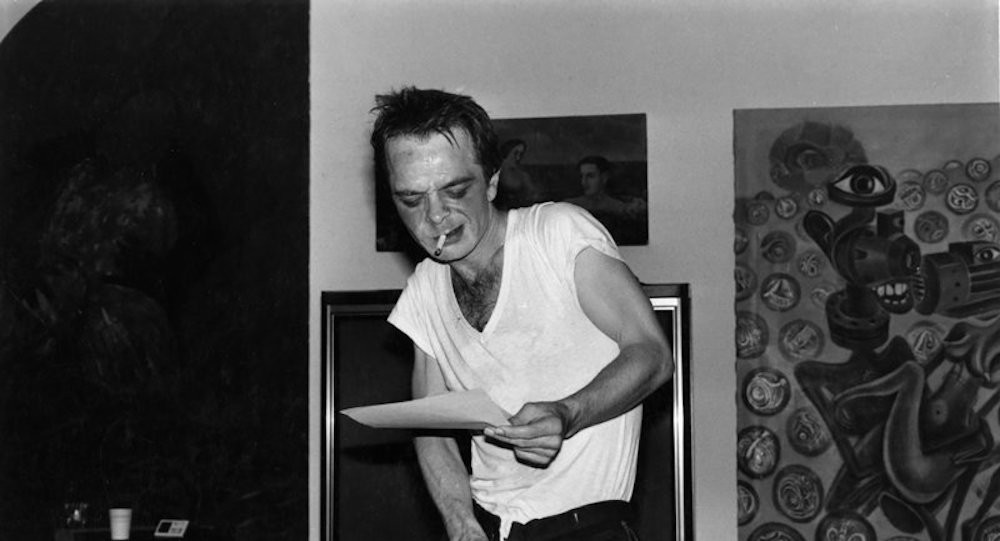

Polymathic novelist, playwright, artist, and critic Gary Indiana, who gained acclaim in the 1980s for his vinegary and irreverent writing on art in the Village Voice, has died. He was seventy-four. His death was first reported by Frieze in the early hours of October 24. Indiana is perhaps best known for his true-crime trilogy inaugurated in the late 1990s—Resentment: A Comedy; Three Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story; and Depraved Indifference—addressing the warped disregard for human life that characterized the turn of the millennium. Widely lauded for what he called “narrative porn” and what critic Christopher Glazek described as “deflationary realism,” he possessed a brash, vivid, and unsentimental writing style that lent both his fiction and his nonfiction a strutting confidence that elevated whatever subject was at hand. A feared and revered figure in the worlds of art and literature, he remained unimpressed with himself. “I call myself a ‘talented amateur,’” he told the New York Times‘s Andrew Marzoni in 2023.

Gary Hoisington was born in 1950 in Derry, New Hampshire, where his mother worked as a town clerk and his father co-owned a lumber company. Accepted to the University of California, Berkeley, at the age of sixteen, he swiftly departed for the West Coast only to abandon traditional education altogether shortly thereafter. Following a stint in Los Angeles, where his job as a receptionist for an inner-city medical clinic gave him access to “an endless supply of pharmaceutical amphetamines,” he moved to New York in 1978. Under his newly chosen moniker of Gary Indiana, he embarked on a career as an actor and playwright in the city’s burgeoning downtown theater scene, writing and acting in plays including Curse of the Dog People (1980) and The Roman Polanski Story (1981) at such appealingly disreputable venues as Club 57 and the backyard of actor Bill Rice’s East Village studio. He was active in experimental film as well, appearing in works including Michel Auder’s Seduction of Patrick (1979) and A Coupla White Faggots Sitting Around Talking (1980); VALIE EXPORT’s The Practice of Love (1985); and Christoph Schlingensief’s Terror 2000: Intensivstation Deutschland (1992), in which his character is slaughtered by a machine-gun-wielding Udo Kier. “I wasn’t trained, and I certainly didn’t have the technique of a professional,” he told Tobi Haslett in a 2021 interview for the Paris Review. “Directors would cast me because of the way I was, not what I could pretend to be.”

In 1985, having brought his inimitable voice to pieces for Artforum and Art in America out of financial necessity, after a friend suggested he take up writing in order to help pay the rent, he was offered the role of art critic for the Village Voice, which he would go on to hold through 1988. In his time there, he churned out uncensored opinions on artists both famous and obscure, seemingly guided by a hot internal lodestar and unswayed by sales figures, popularity, or public opinion. “The first thing to say about Gary Indiana as an art critic is that he was humane,” wrote Christian Lorentzen in Artforum in 2019. “His harshest judgments were arrayed against various forms of cruelty, lifelessness, and greed.” Indiana brought to bear a keen eye, an incisive intelligence in his reviews for the publication, which were collected in the 2018 volume Vile Days: The Village Voice Art Columns, 1985–1988.

While still at the Voice, Indiana published two collections of short stories, 1987’s Scar Tissue and Other Stories and 1988’s White Trash Boulevard. His first novel, Horse Crazy, about an intense gay relationship in the time of AIDS, which ravaged his community, appeared in 1989. He shifted his attention to producing fiction and long-form articles on topics ranging from the trials of Jack Kevorkian to the California porn industry, while continuing to contribute criticism to outlets including Artforum and Vice. In 1992, he cowrote Ron Vawter’s one-man show Roy Cohn/Jack Smith, penning an imaginary speech for Cohn after he and Vawter failed to turn up the transcript of a talk Cohn had given at a dinner during which he attacked gay rights. “One of my earliest memories is of Roy Cohn whispering in Joe McCarthy’s ear on television,” he told the New York Times’s Stephen Holden that year. “The Army-McCarthy hearings and the Rosenberg executions were an indelible part of my childhood.” Conflicted real-life figures remained a touchstone for him, as embodied by the aforementioned true-crime trilogy consisting of 1997’s Resentment: A Comedy, which took as its subject the murderous Mendendez brothers; 1999’s Three Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story, about the killer of designer Gianni Versace; and 2002’s Depraved Indifference, about the con artist and convicted killer Sante Kimes.

Though he professed last year to be suffering from “writer’s hesitation,” Indiana remained wildly prolific throughout his life, producing other notable volumes of fiction including Rent Boy (1994) and Do Everything in the Dark (2003) as well as numerous nonfiction books on Andy Warhol, Dike Blair, and Tracey Emin, all written after 2010. As an artist, too, he was a force to be reckoned with, working mainly in the fields of video and photography. His 2013 video Stanley Park, which linked the consequences of human-effected environmental deterioration to ever-more repressive governmental policies, was included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, and that same year, his A Significant Loss of Human Life, which expanded on these themes and placed them in the context of Marxism, was one of twenty-two pamphlets issued by Semiotext(e) ahead of the Biennial.

In the last decade of his life, Indiana traveled frequently between Havana and a sixth-floor walkup apartment on Manhattan’s East Eleventh Street. Though his writings loomed large, Indiana, described by Haslett as “a mix of prince and punk,” himself did not; the White Review’s Michael Barron in 2016 wrote of being shocked to find him sitting demurely and diminutively in a corner of New York hot spot Lucien, sipping water and munching on table bread. Still, his star continued to shine, his tawdry 2015 memoir I Can Give You Anything but Love reaping accolades; the 2022 collection Fire Season: Selected Essays 1984–2021 showing him to have been prescient regarding both art and politics; and a 2023 reprint of Rent Boy reaching entirely new audiences. At his death, Indiana was at work on a novel. The Times’s Marzoni asked him how he would know it was finished.

“You just know,” Indiana replied. “Nothing is ever completely finished, but I know when I get to the end of something that this is the last scene of the book, or this is the last shot of the video. It tells you: enough already.”

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. By Alex Greenberger

Senior Editor, ARTnews

Gary Indiana, a writer whose acid musings on gallery shows and artists defined a era in art criticism, has died at 74. Frieze first reported his death on Thursday morning.

Indiana wrote novels, essays, and magazine columns, often bridging the gap between literary writing and criticism in the process. Although he was widely known as an art critic for the Village Voice during the mid-1980s, and even though he has continued to write literature and art criticism in the decades since, Indiana had by the beginning of the 21st century faded into relative obscurity, with many of his books going out of print. In a 2014 profile of Indiana, M. H. Miller dubbed him “one of the most woefully under appreciated writers of the last 30 years.”

But within the past decade, there has been what Tobi Haslett called an “Indiana renaissance.” Indiana’s novels are once again widely circulated, largely thanks to the publishing houses Seven Stories Press and Semiotext(e), and his criticism has been republished online and in essay collections after being largely inaccessible for many years.

When that essay collection was published, Zachary Fine wrote in Art in America, “Indiana has been at it for decades, and if contemporary literary and art criticism in America is often dismissed for its tendency toward meekness and puffery, then one solution might be for more critics to read Indiana.”

For many, however, Indiana will always be aligned with his period at the Village Voice, where he served as chief art critic from 1985 to 1988. The Voice was one of the few New York–based publications that regularly published reviews of gallery shows at the time, and one might have expected that Indiana would have continued that tradition. Instead, what he produced were columns that excoriated the art world for its obsession with power and social clout.

Sometimes, he obliquely wrote around exhibitions he was tasked with reviewing. “One review of a Julian Schnabel show was just a series of quotes culled from fashion magazines about Mr. Schnabel’s house and clothes, interspersed with reports of terrorist attacks and Stockholm Syndrome,” wrote Miller in his Gallerist NY profile of Indiana. Another involved comparing a Warhol “Mao” painting to “a gold American Express card being brandished at Zabar’s to pay for three bagels.”

According to that profile, while on the job, Indiana wrote a note to himself: “be bitchy.” The remark was emblematic of his writing more broadly.

And should there be any doubt about what Indiana thought of his own Village Voice columns, he once wrote that they were “a bunch of yellowing newspaper columns I never republished and haven’t cared about for a second since writing them a quarter century ago.”

Gary Hoisington was born in 1950 in Derry, New Hampshire. His father was a partial owner of a lumber company, his mother, the town clerk. When he was 16, he departed New Hampshire for California, with plans to study at the University of California Berkeley. He ended up bouncing around the country, living first in Boston, then in Los Angeles, where he took a day job as a paralegal and a night job at a movie theater. He changed his last name to Indiana, though he later said he ended up regretting the alias he concocted.

In 1978, Indiana moved to New York and began to write plays and films. But the money earned was not enough for him to pay off rent, so at a friend’s suggestion, he tried his hand at art criticism. He remained uncomfortable with the notion that he was a professional writer. Years later, in a 2023 T magazine interview, he described himself as a “talented amateur.”

“It took years to get people to stop writing about me as an art critic, which was something I never in a million years wanted to be in the first place, and I certainly didn’t consider myself an art critic in any conventional sense. I did it for two and a half years,” referring to his time spent at the Village Voice between 1985 and 1988. “That’s not much in a life as long as the one I’ve had.”

Although Indiana continued to write for art magazines such as Art in America and Artforum, he was also prolific as a novelist. His first novel, Horse Crazy, about an art critic in love with a mercurial younger man, was started while Indiana was still at the Voice and was published in 1989, after he left. The book has been praised for encapsulating the mode of 1980s New York, which was haunted by the AIDS epidemic and paranoia. William Boroughs compared it to the queer writings of Jean Genet, praising Horse Crazy as “fascinating to every man, no matter what his sexual tastes.”

Indiana went on to write a range of other novels, including 1999’s Three Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story, a heavily stylized fictional retelling of the life of Gianni Versace’s murderer.

But Indiana’s writings were only one aspect of his career. He also acted in experimental films by the likes of Ulrike Ottinger, Michel Auder, and Valie Export, and he produced videos and photographs of his own. One of his videos focused on a prison in Cuba, the island nation where Indiana lived periodically over the course of 15 years, and featured shots of jellyfish, which Indiana described as animals “with no brain and a thousand poisonous tentacles collecting what you could call data.”

Indiana has become a cult figure to many, but he did not seem much interested in the admiration he received. He spoke of his writing unglamorously, as though it were no big deal.

When T asked how he knew a piece was done, he said, “You just know. Nothing is ever completely finished, but I know when I get to the end of something that this is the last scene of the book, or this is the last shot of the video. It tells you: enough already.”

The World’s Premier Art Magazine since 1913. Subscribe today and save!

Sign Up for our Newsletters

Get our latest stories in the feed of your favorite networks

We want to hear from you! Send us a tip using our anonymous form.

Subscribe to our newsletters below

ARTnews is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Art Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved.