This year’s GCSE results are out. And, as always, we’ve crunched the numbers to bring you all the facts and figures that you need to know.

Many of the headlines about this year’s A-Level results focused on an increase in top grades compared to last year, and even more so when compared to pre-pandemic.

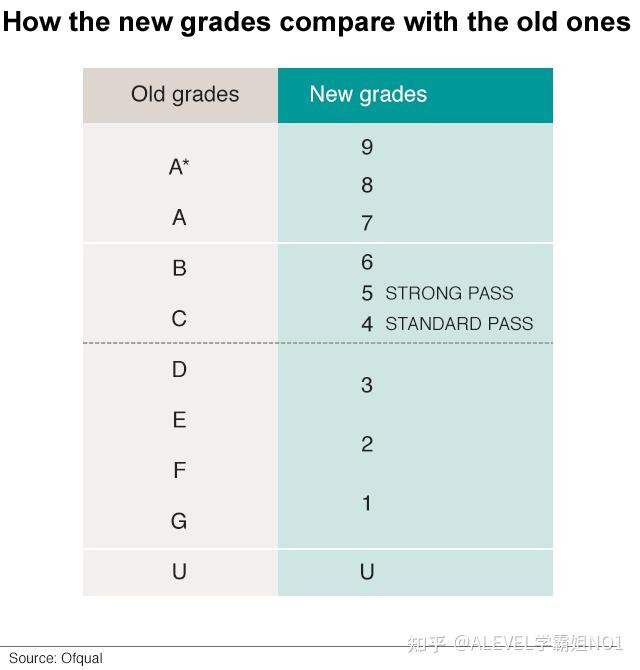

And at GCSE, there has also been a (very small) increase in top grades: they are up from 22.4% of entries last year to 22.6% this year. And both figures are higher than pre-pandemic: in 2019, the proportion of entries graded 7 or above stood at 21.9%.

Having said all that, grades this year do remain broadly similar to last year and pre-pandemic: the differences are far smaller than the more dramatic changes to grading that happened in 2020 and 2021, following the cancellation of public exams and the gradual return to closer to pre-pandemic levels.

In 2021, when grades were at their highest, 30% of GCSEs received a grade 7 or above; this year it was 22.6%.

Top Grades Remain Steady But Resits Are Up

If we look at entries from all students in England, there is a fall in the proportion of entries grades 4 or above in both English language and maths. In English language, the rate is down from 64.2% to 61.6%, and in maths from 61.0% to 59.6%.

This might seem alarming at first glance, but the large fall in English language rates is largely driven by an increase in resits (of which more below). The rates for 16 year olds are much more similar to last year: 71.6% vs 71.2% in English language and 72.3% vs 72% in maths. For entries from pupils aged 17 and older, the proportion achieving a grade 4 or above has dropped fairly dramatically in English language: from 25.9% last year to 20.9% this year.

A Look At Regional Trends

Grading in England may be broadly similar to last year, but that’s not the case in Wales or Northern Ireland.

While in England, grades last year were close to pre-pandemic levels, grades in Wales and Northern Ireland remained higher. We saw a similar pattern at A-Level last week. This is partly because qualifications are not regulated by Ofqual, as in England, so different policies around the return to pre-pandemic levels were applied. It is also the case that there are differences in GCSE content, grading and modularity between England, Wales and Northern Ireland. How comparable they actually are is unclear (to us at least).

This year grades are similar, if slightly higher, to 2019 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (albeit higher by less than 0.1 percentage points in NI).

Exam Entries And Performance Across Subjects

Across almost all subjects, there was barely any change in the percentage of pupils awarded grades 9-4 this year. Results for 2024 (and 2023) were largely in line with those in 2019.

The exceptions were computer science, in which Ofqual had instructed boards to make adjustments to raise grades, and statistics, in which attainment in 2023 and 2024 remained below 2019 levels. Entries in statistics have increased 70% since 2019. The inference we make is that the recent cohorts had lower prior attainment than the 2019 cohort.

At grades 9-7 we see a similar pattern with computer science and statistics.

We also see an increase in results in French (2 percentage points) and German (3.5 percentage points), again after Ofqual instructed boards to make an adjustment. However, the results of this were less apparent at the grade 4 borderline, although there was a 0.6 percentage point increase in both.

In terms of 9-7 grades, there was little change in results for each centre type between 2023 and 2024.

Performance By School Type

Taking the data published by Ofqual at face value, secondary selective schools were the highest attaining, followed by independent schools. Both improved by 1 percentage point compared to last year. To some extent you would expect these schools to improve by a greater margin compared to other schools. Last year, for example, pupils at these schools would have been disproportionately located at the upper end of the grade 6/7 boundary and thus more likely to benefit from any national uplift in performance.

There was a slight (1.5 percentage point) increase in attainment among schools classifying themselves as free schools. Whether this is driven by existing free schools improving or new schools receiving results for the first time we will find out in due course.

We wouldn’t read too much into these figures at this stage. The data for colleges will largely consist of 17 year olds, whereas results for schools will largely consist of 16 year olds. In addition, the categories are not mutually exclusive. Many selective (grammar) schools are academies, for example. It would be better to wait for the DfE statistical release in October for analysis by centre type.

Regional Trends In GCSE Attainment

At regional level, there were barely any differences in results at grades 9-7 compared to 2023.

Across all regions, results across all regions were broadly in line with those in 2019. The exception is London, where attainment in 2024 was slightly higher. London seemed to weather the Covid-19 storm better than other regions, as we wrote this time last year.

That said, and as we wrote with Simon Burgess, the north/south divide in school performance is mostly a distraction. Most of the variation in school performance is very local, between nearby schools.

Changes In Subject Entries

Some subjects, particularly statistics, have seen big percentage increases in entries this year. And entries in just two subjects – drama and performing / expressive arts – are down. The fact that entries have increased (almost) across the board is largely down to an increase in the population of 16 year olds.

But we should bear in mind that a big percentage increase does not necessarily mean a huge increase in numbers. Several of the subjects with a big increase in entries still have a low number of entries overall.

Subjects with both a relatively high number of entries and a relatively large increase in entries this year include computer science, business studies and Spanish.

Last year, we highlighted the steady decline in entries to GCSEs in performing arts subjects. And we’ve seen above that entries are down again in some subjects this year. So let’s see what happened in more detail:

Entries to drama stayed roughly the same as last year, despite the size of the overall GCSE cohort increasing. Entries to performing and expressive arts declined slightly again. But, perhaps surprisingly, entries to music increased. And by a greater percentage than increase in the size of the cohort.

It’s hard to say whether this signals a reversal in the long-term decline in entries to music at Key Stage 4, as there are a number of popular vocational and technical qualifications in performing arts subjects which aren’t included here. These tend to be quite common in music. But we note in the section on tech awards below that there has been a drop in entries in arts, publishing and media, which includes music among many other. It may be the case that some schools have switched back to GCSE rather than offer the reformed tech award. We will look into this later in the year.

Resits And The National Reference Test

We’ve seen that the overall sizes of the re-sit English and maths cohorts have increased since last year. This is as expected: the percentage of 16-year-olds who received a grade 4 or better last year was lower than the year before due to pandemic grading arrangements.

With this cohort expansion, we might also have expected to see a higher proportion of grades awarded a 4 or better. That’s because pupils who were awarded below a grade 4 at age 16 during the pandemic years, when grading was more generous, would have been lower attaining on average if judged by the same standards as those who achieved below a grade 4 at age 16 last year, when pre-pandemic grading norms returned.

In maths, we have seen a slight increase: 16.4% of students aged 17+ achieved a grade 4 last year vs 17.4% this year. But in English, there’s been a sizeable drop: from 25.9% last year to 20.9% this year.

To dig into this, we can look at results by age. Here, we compare this year with last year, and with pre-pandemic:

The increase in maths attainment is largely driven by those aged 17. In English, results actually fell among 17-year-olds, although the drop was bigger for those aged 18 or older.

One question this chart poses is why results for 17-year-olds in both subjects (though particularly in English) aren’t more similar to 2019. At face value this would suggest that that the quality of work produced by 17-year-olds (relative to 16-year-olds) has fallen. Is this really the case?

The National Reference Test (NRT) has not been around for that long: it was first introduced in 2017. It is supposed to provide independent evidence about whether standards in English and maths are improving over time to help determine whether GCSE results should improve.

This is done by looking at the results from a set of English and maths tests that are given to a sample of Year 11 pupils in the spring before their GCSEs. These results should show if performance among the current cohort is higher or lower than usual, and could potentially be used as evidence to adjust GCSE grade boundaries to reflect any differences.

“In practice, Ofqual have been cautious about using the test in this way, and this year did not make any adjustments to grade boundaries based on the results, despite a slight drop in attainment in English compared to 2023 (albeit with overlapping confidence intervals). It is, perhaps, fair to ask why the test is still being administered if it is not to be used for grade boundaries.

But the results are still interesting in themselves.

We include results for all years since the test was introduced in the table below, but the important comparison is between 2017, the baseline year, and this year (highlighted on the table).

This comparison reveals a fall in performance in English language, and a small increase in maths. Given the disruption caused to this year’s cohort by the pandemic, a fall in performance in both areas would perhaps not be surprising.

The increase in maths and fall in English is, perhaps, a little unexpected, given that primary school attainment measures show a fall in maths and similar levels in reading, compared to pre-pandemic.

A Closer Look At The Gender Gap

On average, female students achieve higher grades at GCSE than male students. But there have been some changes to this gender gap in recent years.

In the years leading up to the pandemic, the gender gap in top grades decreased slightly: from 7.7 percentage points in 2016 to 6.5 in 2019. And this difference was mainly driven by male students achieving higher grades: the proportion of entries from male students receiving a 7 or above increased from 17.6% in 2016 to 18.6% in 2019, while for female students there was a small fall of 0.2 percentage points over the same period.

During the pandemic, the gap increased again to a peak of 9.0 percentage points in 2021. While the grades of both male and female students increased from 2020-22, the grades of female students increased more sharply.

We might have expected to gender gap to fall back to 2019 levels both last year and this year. But that hasn’t quite been the case. It is actually smaller than pre-pandemic: 5.6 percentage points this year compared to 6.5 in 2019. And it’s fallen very slightly – by 0.2 percentage points – since last year.

Overall, the proportion of top grades this year is 0.8 percentage points higher than pre-pandemic. But this is not evenly split between male and female students: the proportion of entries graded 9-7 from male students is 0.9 percentage points higher than 2019, while from female students it is just 0.4 percentage points higher.

TES have written a thoughtful piece about what the reasons behind these changes might be, which is well worth a read for anyone who wants to know more about the gender gap.

Performance In Tech Awards

This year, results in reformed Tech Awards were issued for the first time.

This covers a range of vocational and technical qualifications at level 2 and below studied both by Key Stage 4 pupils and post-16 students.

Ofqual use the language of “strengthening” awards. Briefly, this seems to mean that pupils take their external assessments at the end of the course, and that the external assessments contribute at least 40% of the total marks of the qualification. Many awarding organisations have taken the opportunity to change some of the units within qualifications.

Given that (we think) that the data published by Ofqual includes both Key Stage 4 and post-16 students, it’s not straightforward at this stage to assess the impact of the changes on the attainment of either group.

Overall, there seems to have been a slight drop in entry numbers, particularly in awards relating to leisure, travel and tourism and arts, media and publishing.

In addition, attainment seems to have fallen slightly. This is typical when qualifications are revised. Results then improve as teachers become familiar with the new content (the sawtooth effect). We illustrate this with a chart showing attainment in awards with this most common grading structure (such as BTEC tech awards).

In turn, this could have a small effect on schools’ Attainment 8 scores (more specifically the open slots of Attainment 8), which we’ll keep an eye on.

Looking Ahead

Just to finish off, it is important to recognise achievements in vocational qualifications alongside GCSEs. But the way they are described (e.g. with respect to their grading structure) makes analysis very hard to communicate.

Make sure you don’t miss any of FFT Education Datalab’s research by signing up to get our newsletter or our latest blogposts by email.