A few months after Hanif Kureishi had a fall that left him unable to move his limbs, he was visited by a friend bearing an envelope of photographs. It included one taken of the writer in 1993 at a book-signing for his first novel, The Buddha of Suburbia. It showed him sporting a Levi’s jacket that he still owned; otherwise he could barely recognise himself. His fashionable long hair was pinned behind his ears, light was illuminating the smooth skin on his “pixie-like” face. Now, in his late sixties, Kureishi was gaunt, unshaven and trapped in bed, unable even to get into a wheelchair “due to a fissure in my arse”.

The picture reminded him of everything he had lost and, as he recounts in his searing new memoir Shattered, he was not sure he wanted it pinned on a wall opposite his hospital bed. “I want to work. I want to work every day, I want to be a real person,” he replies, speaking to me over Zoom from a west London home that has been reconfigured for his 24-hour care. “I don’t want to be just a suffering body. I want to be like Emma, working and getting on with shit — it really matters to my dignity.”

Kureishi asks his adult son Sachin to push his coffee cup towards him, so he can sip the drink through a straw. It is the first indication I have of his disability: on screen, he looks and sounds largely as I remember him from an interview a decade ago. At my request, he shows me what he can do, lifting his arm a little. But he can’t use his fingers at all, meaning that holding a cup or lifting a pen are impossible.

Writing now involves memorising things — “I fling a net over more or less random thoughts, draw it in and hope some kind of pattern emerges” — and dictating them to Carlo, Sachin’s twin brother, when he is available. An advert placed by the Royal Literary Fund in the theatre programme for The Buddha of Suburbia asks for donations to allow Kureishi to “continue to function as a writer”.

Parts of the memoir were also dictated to his 54-year-old Italian partner, Isabella (which becomes deliciously awkward when he recalls having a threesome as a younger man), while he began working with Rice (who is also on our Zoom, beaming in from her home in Frome, Somerset) before his accident. There were workshops at the National Theatre, where Rice recalls Kureishi playing cricket with the actors, but when the play was staged in Stratford-upon-Avon this year Kureshi was only able to watch streamed performances. More recently, in anticipation of its transfer to the Barbican in London, he attended rehearsals in Clapham. It’s a project that has made them close: Emma has visited Kureishi in three hospitals. “There were long periods when we weren’t thinking about work,” she says.

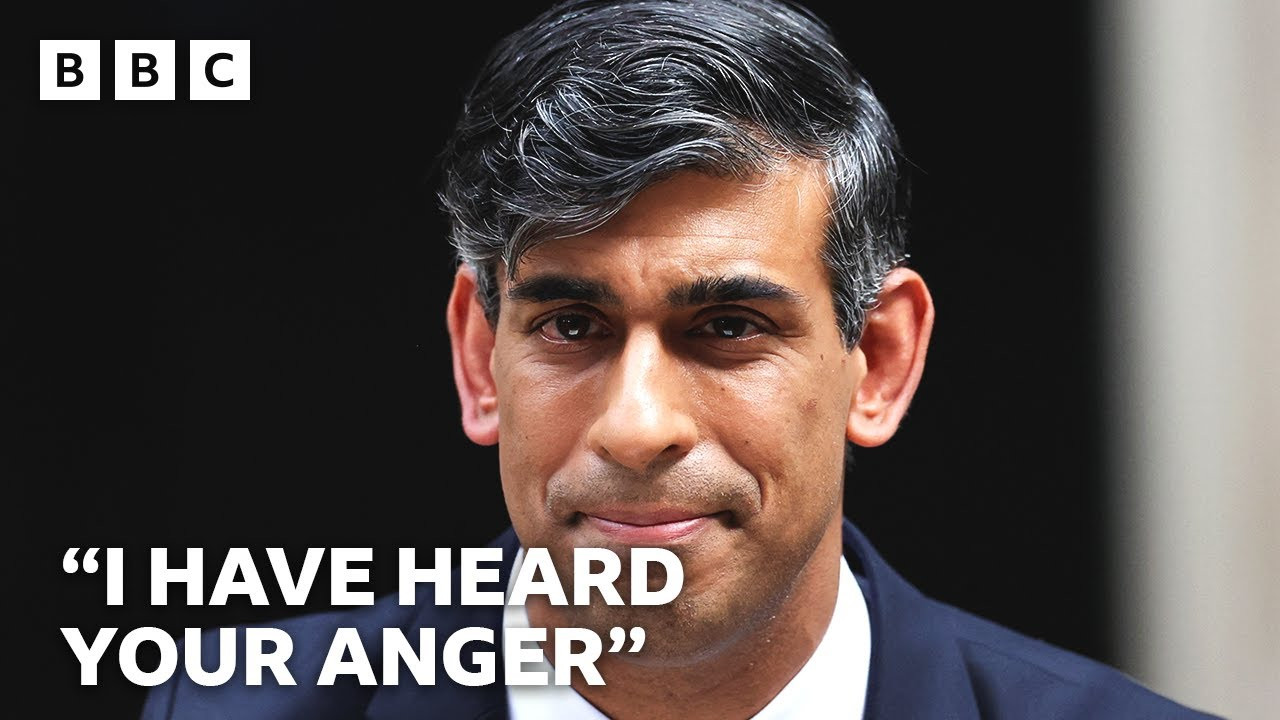

Kureishi’s coming-of-age tale revolves around the 17-year-old Karim as he navigates south London in the Seventies, and its Nineties BBC TV adaptation was hugely important for a generation of British-Asian writers like me, who saw themselves in British literature for the first time. “Initially I felt, ‘There’s my family and I’ve put them on the stage and have I mocked them? And then later, when I saw the audience’s reaction, I revised my opinion. Because the piece is very warm and humorous, and it’s very loving towards those characters. It doesn’t humiliate them. It’s one picture of our family’s journeys from the third world to the UK and the story of our struggles here and how we overcame them. Now we have the opposition leader Rishi Sunak; we have Suella Braverman. That just shows how well we’ve done in this country, doesn’t it?”

The raised eyebrow, and subsequent description of Braverman as “the revenge of colonialism”, suggests a degree of sarcasm. As does Kureishi’s claim that the contradictions of race in The Buddha of Suburbia have been exchanged in the 21st century for new paradoxes.

“I mean, in the 1970s, Indians were either P***s on the street, pursued by skinheads with baseball bats, or we were sort of gurus who knew the truth about human spirituality. There was this double picture of us, which has gone. But there are always new cliches around.”

“We’re much better off and much worse off. And we’re still certainly under the culture that seems to blame immigrants for everything. When I was in hospital for a year, I noticed that everybody I ever met in the NHS was from somewhere else. We’re still importing people from the former third world to staff our hospitals. At the same time, we’re talking about cutting immigration. So we have what you might call a deadlock at the heart of our society about immigration.”

The author of nine novels, including The Black Album, Intimacy and The Nothing, adds that he’s looking forward to seeing how a young, racially diverse London audience responds to a story about south London in the late Seventies, with its high unemployment, high inflation, food shortages and strikes. The parallels are obvious, although both he and Rice are aware that young people are different now — not least when it comes to sex — one of the book’s main preoccupations.

Indeed, the accident has transformed Kureishi’s entire approach to the matter: while having blown up some relationships for it, and written so much about it so frankly (his 1998 novel Intimacy was the story of a man leaving his wife and sons, while the 2006 film Venus was about an elderly actor who is attracted to his friend’s great-niece), he now writes that sex is “a major absence, and a puzzling one. I now look at sexuality from another point of view, that of a disinterested spectator. I wonder what all the fuss is about.”

In person, he adds: “In the early 1960s, of course, there was a huge amount of work done on sexuality, and there was a lot of pressure on people, particularly in the 1970s, to have sex, even if they didn’t want to. And I’m aware now with my three children that they’re far less interested in sex than we were in the 1970s when it seemed such a novelty. But if you ask me, we’re still thinking about it — certainly in terms of gender, certainly in terms of sexual assaults and harassment and rape and so on. It’s not a subject that will ever go away.”

Then there are the changed attitudes to money, addressed in the book and play through Karim’s father’s scepticism about western materialism — a scepticism not many south Asians share nowadays. “Yeah, [young people] are really crazy about money. My kids and their friends are really concerned about their standard of living, about their clothes, apartments and money in a way that we never thought or talked about in the 1970s because it was impossible that you would ever become rich in any shape or form.

“We were really interested in being in bands, being photographers, being involved in fashion, writing or film-making. But we never thought any of this was going to make us rich. There’s a new kind of corruption of money that I really don’t approve of.”

Finally, there are the drugs that feature in the book (less so in the play), as Karim challenges social norms, and which also seem to have a declining influence upon the young. “I like drugs but I prefer drugs like Ecstasy and LSD,” Kureshi proffers. I note that he is talking in the present tense. “Yeah,” he laughs. “These days, I take huge handfuls of meds to keep my f***ing body moving. I don’t have much time for recreational drugs. I’m resting on the sidelines now, mate.”

Regardless, there are some entertaining recollections in his memoir about drug-taking, not least with his sons. They serve as a reminder that Kureishi is not only one of our most prescient writers, penning My Son the Fanatic years before religious fundamentalism became a national concern, but also one of our boldest. During our conversation he rails against the emergence of sensitivity readers and the idiocy of anxieties about cultural appropriation. “I don’t give a shit,” adds the man who not long ago made this newspaper’s tally of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945. “I think work should be dirty and full of love and filth.”

There’s a reminder in the book that Kureishi’s career could have gone in a different direction. The Buddha of Suburbia came about at a time when he was being courted by Hollywood, having been Oscar nominated for the script of My Beautiful Laundrette. “I was in Los Angeles for a while after the Oscars and it suddenly occurred to me that I was British. I wanted to write about Britain. The stories and the characters were all here in Britain and that was where my subject matter was.”

Now, two of his three sons, Carlo and Sachin, are following in his footsteps, working as screenwriters and journalists. The three of them have been working together for some time: before the accident they would walk around west London “talking about stories, structure and how to succeed in the industry. We would start with an idea or image and then string it out, develop it, until it began to look like a whole narrative. It was fun and satisfying — we enjoyed being together.”

Now, as well as caring for their father, along with other family members and professional carers, the three are writing a film “about a man like me who falls upside down on his head one day”.

Kureishi, who has taught creative writing for decades, admits that the working relationship is an unexpected development given he wasn’t a particularly attentive father. “I admit that the early days were difficult, if not nasty, and even hair-raising on occasion,” he writes. “It took me a few years to start enjoying them and along the way I found myself in many uncomfortable situations. I hated taking them to the various activities the times demanded, like karate, football and swimming, which involved wasting hours with the parents of other kids, whom I found utterly boring.”

But now that he is, in his words, a “turtle on its back”, his relationship with his children is one of the main things that keeps him going.

The urgency of the work he’s doing with them is evident in a new directness in both Kureishi’s writing and his speaking tone. As he puts it to me: “You shit or you get off the pot when the other person is waiting to write it down. I have to say it there and then. It’s more direct.” Finally, the urgency is evident in his desire to get on with his working day: he wants to use the time he has to write, rather than to talk about writing.

“I think traumas can stimulate people to do new things because they have to resolve the trauma, or explore it, or put it to bed in some shape or form. The trauma of racism caused me to be a writer, you could say. And the trauma of this accident has caused me to write what I am now. I must go.”

The Buddha of Suburbia is at the Barbican until Nov 16, rsc.org.uk. Shattered by Hanif Kureishi is out now (Hamish Hamilton £18.99 pp336). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members

Shattered, the novelist’s account of his 2022 accident and new life since, is caustic, contemplative and characteristically unsparing

Throughout his career, Hanif Kureishi has specialised in the unsparing. His first novel, The Buddha of Suburbia (1990), angered his family with its explicit account of the sexual, druggy and clearly autobiographical adventures of a mixed-race teenager desperate to escape his oppressive home. In 1999’s Intimacy, an adulterous narrator prepares to leave his partner and two young sons – just as Kureishi did – having decided that “there are some f---s for which a person would have their partner and children drown in a freezing sea”. Now, in this intense memoir, he applies the same unsparing approach to his new status as a “near vegetable”, after a freak fall in Rome on Boxing Day 2022 left him paralysed, aged 68.

At the heart of Shattered is a question posed by Kureishi’s iPad during an episode of Better Call Saul when “the screen went black and a legend appeared, asking ‘Are you still there?’”. “That is an interesting question,” Kureishi admits – and much of this book is an anxious but ultimately successful attempt to prove the answer is “yes”. Spending a year in various Italian and London hospitals, he realises his entire identity is in danger of being reduced to that of “a patient”, so he resolves to write his way back into selfhood.

Part of the process is to reassemble the memories of his Bromley childhood, in which his father takes on a heroic role as the man who introduced young Hanif to books and jokes. (“My mother was the most boring person I ever met,” he notes unsparingly in passing.) Kureishi is also keen to remind us – and himself – that he was quite a guy in his prime: much in demand in Hollywood, no stranger to threesomes in Amsterdam, and blessed with plenty of famous contacts, including a cheerful drinker with an eye for young women called Samuel Beckett.

Nonetheless, what Kureishi really wants us – and himself – to know is that he is, first and foremost, a writer. Reading Shattered, I often thought of Keith Richards’s autobiography, where the most animated passages are not those about his globe-spanning fame or rollicking hedonism, but the ones in which he discovers a new guitar tuning. Likewise for Kureishi, it’s when discussing writing that he seems most alive. Touchingly, he’s delighted that he can still do it. Unable to use his hands, he has to dictate the words – originally for the online platform Substack – from his hospital bed, to his Italian partner Isabella or one of his three sons. The technique accounts for the overwhelming immediacy, because Kureishi speaks about everything as “it occurred, capturing the raw feeling of the moment, the exact horror experienced, without reflection”.

In recent times, other authors have provided reports of their near-death experiences: see, for instance, Salman Rushdie’s Knife or Maggie O’Farrell’s I Am, I Am, I Am. But in both of those, enough time had passed for the writers to process their experiences. Kureishi’s pour out unfiltered: “Excuse me for a moment, I must have an enema now.” For this reason, his thoughts can be fairly random, as he free-associates his way from the importance of eyebrows to the evolution of pornography since the 1960s.

Yet all the time, there’s a suitably unsparing acknowledgement that none of this, and especially not the memories of his past glories, makes any difference to his condition – aka “reality” (a word that clangs ominously through the book). Kureishi pines for the pleasures he once took for granted: watching Match of the Day with a glass of wine, going to the toilet unaided. However much a part of him can’t believe he’ll never get them back, another part is bitterly aware they’re gone forever. After the incurable “rupture” between his old and new lives, “in my mind I’m still living in the first, while in my body, unfortunately, I am in the second.”

Perhaps the biggest rupture is sex. In his pomp, as Intimacy suggests, Kureishi’s novels were shot through with a commitment to following the libido wherever it leads and whatever damage it causes. Now, he can’t see what all the fuss was about, wondering why sex “was important, mattering so much to so many”. Meanwhile, there are signs of a new mellowness in his many hymns to the kindness of friends and family – including the partner and sons he abandoned – and in his pledge to be kinder himself.

Not that he has become a complete softie. Unexpectedly for a lifelong anti-Thatcherite, he writes that “in the 1980s selfishness was the character ideal of the age, and f---ing hell was it fun”. Hearing of the rise of “sensitivity readers” to vet new fiction for “sexism racism, cultural appropriation and so on”, he launches a full-throated attack on the “North Korea of the mind” created by “an element of the Left which is bursting with aggressive self-righteousness and self-defeating puritanism”.

By its nature, Shattered is not a coherent book. It contains a fair amount of repetition and some flat-out contradiction. Both, though, feel like an authentic depiction of Kureishi’s whirring mind, particularly in the constant alternation of hope and despair. Indeed, pretty much the only thing about which Kureishi isn’t candid is the fact – surely galling – that, 40 years into his career, he’s still best-known for the screenplay of My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and The Buddha of Suburbia (1990). I have my own not-terribly-sophisticated theory as to why: he hasn’t written anything as good since. Until, that is, Shattered – which, if there’s any justice, should give Kureishi’s interviewers, and even his own Twitter biography, a third work with which to introduce him.

There’s always a suspicion that memoirs of trauma are opportunistic, even slightly shameless, attempts to titillate; but this book is much too heartfelt for that. Kureishi is almost literally writing for his life. At one point, he sternly declares that writing is “not therapy for the writer but entertainment for the reader”. Yet, while the entertainment here is of a complicated kind, Shattered shows, triumphantly, that it’s possible to combine the two

The author’s memoir recounts his life since the accident that left him paralysed and mixes typically forthright takes on sex and scatology with ruthless candour about his physical state

In Rome on St Stephen’s Day 2022, the writer Hanif Kureishi took a fall that left him almost completely paralysed. Throughout the subsequent year he spent in hospitals – first in Italy, then in his home city of London – confronting the horror of his new reality as a severely disabled person, Kureishi dictated “dispatches” to his wife, Isabella, and his sons, which were published online. Helped by his family, the author has expanded these dispatches into a memoir of catastrophe whose driving question is nothing less than that of how its author is meant to go on: “Paki, writer, cripple: who am I now?”

I imagine that Shattered was at once the hardest and the easiest book Kureishi has ever written: hard because of the irreversibly awful circumstance that occasioned it; easy because, with material this intrinsically interesting – a reversal of fortunes so dramatic and grotesque – any halfway talented writer could fashion something readable. Sure enough, Shattered is an enthralling report on how a person can be forced to reckon with sudden, shocking change.

In news stories about Kureishi’s bedbound writings, I seem to remember the tone of the quoted dispatches being blacker, more despairing than is largely true of Shattered. A writer comfortably middlebrow enough to equate literature with “showbiz”, now that he’s reduced to the condition of “a Beckettian chattering mouth”, with the life he relished receding for ever into the past, Kureishi remains concerned with showing his readers a good time. Shattered is a disaster story with plentiful quips. “Since I became a vegetable I have never been so busy.” “I have to say that becoming paralysed is a great way to meet new people.” “It would be easier for everyone in Italy to learn English than for me to understand Italian.” In one of many passages about a stranger sticking a finger up his arse, he writes: “The last time a medical digit entered my backside was a few years ago. As the nurse flipped me over she asked, ‘How long did it take you to write Midnight’s Children?’”

That novel’s actual author, Salman Rushdie, is a friend of Kureishi who wrote to him every day while he was in hospital. Curiously, both men now have in common the fact of producing books about extreme experience late in their careers: Rushdie’s recent memoir, Knife, recounts how he was stabbed multiple times because his imaginative fancies had enraged the adherents of a religion whose God is apparently at once all-powerful and cripplingly insecure.

But let’s get back to Kureishi’s arse: while it’s his Beckettian mouth that does the dictating, his arse is in some regards the star of the show. It’s continually being probed, assessed, fingered and discussed by doctors and nurses. The indignities of his new regime of shitting and pissing, having his arse wiped by medical professionals and so on, proves a fertile theme. Isabella questions whether his readers really need to hear so much about his bodily functions; Kureishi, who has always had a keen feel for the pulse of human fascination, insists that that is exactly the stuff they want to hear about. He considers writing a hospital story whose title is a question the nurses routinely ask him: Have You Opened Your Bowels?

More than shitting, the bodily function of which Kureishi has long been a notably acute observer is, of course, sex. Now that he’s lost his sexual function “overnight”, he wonders what the fuss was all about, how he’d ever become so preoccupied with a pleasure so fleeting: “All sexuality feels like this to me now: foreign, almost alien.” But still a carnal fire flickers: he envies “able-bodied sexual beings” and hopes that, “eventually, I could be capable of a little light cunnilingus”.

Rather than confine his account to a series of hospital rooms, Kureishi reminisces about his career as a writer (and as a shagger – for the hell of it, he throws in an anecdote about having sex with a young female admirer in Amsterdam while her boyfriend watched). His reflections on the practice of writing are lively, not least when he focuses on the delights and difficulties of writing about sex. The novels of Henry Miller offered the teenage Kureishi “the great thrill of writing with interludes of pornography which you could cheerfully masturbate to”.

Having savoured a hedonistic heyday in the selfish 80s and liberal 90s, Kureishi never lost his taste for pleasure. He mentions “great cocaine nights” he spent with his children, and offers a gaily epicurean maxim: “Sex and drugs go together, like wine and a good meal.” Elsewhere, he expresses dismay – always welcome – at the new culture of sanctimony and timid self-censorship, reserving particular scorn for the inherently oppressive, homogenising work of sensitivity readers. “The writers I prefer, the ones I grew up with, are the wild ones, the demented, the rude ones who don’t give a damn.” Kureishi notes that his celebrated debut novel, The Buddha of Suburbia, with its cheerful abundance of racist slurs, might not even have been published today.

There are periodic lapses in Kureishi’s customary perceptive cruelty. For instance, he mentions deciding that he has belatedly come to see the value in marriage and will propose to Isabella – but no admission is made that his collapse into total dependency, with the radical shift in power it entails, may have inspired his new attitude. If this were a Kureishi novel, we might enter here into the disabled man’s feverish insomnias as he jealously obsesses over what his beloved gets up to when she leaves him alone after visiting hours. (If you think I’m in poor taste here, bear in mind that this is a novelist who, in a seemingly autobiographical novel about a writer who abandons his family, penned the memorably hyperbolic adage, “There are some fucks for which a person would have their partner and children drown in a freezing sea.”)

The ruthlessly candid Kureishi of old resurfaces when Isabella, tending her man with loving devotion, pauses and asks him if he’d have done the same for her: “I couldn’t answer. I don’t know.”

To anyone who’s ever enjoyed Kureishi’s books, it’s impossible not to read Shattered in a spirit of generosity and communion. For all its misery, his ordeal seems to have given him a new access to compassion, forcing him to notice an entire category of people – those who are disabled – who were previously all but invisible to him. Inevitably, Shattered is its own lifeline, and a neat exemplar of what we mean when we describe a book as “necessary”: its value for readers is at one with its urgency of expression to the human being drowning in the experience it attempts to redeem.

Shattered by Hanif Kureishi is published by Hamish Hamilton (£18.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply