Homogeneity brings a risk of limited perspectives and shared biases. Leadership teams must include a diverse range of talent, thought, and experience. However, traditional leadership pipelines often result in leaders who think alike, interfering with effective decision making. The general lack of diversity is exacerbated by neuroexclusion in leadership, which overlooks the unique perspectives and notable strengths that neurodivergent individuals can bring, such as innovative problem solving and detailed analytical skills.

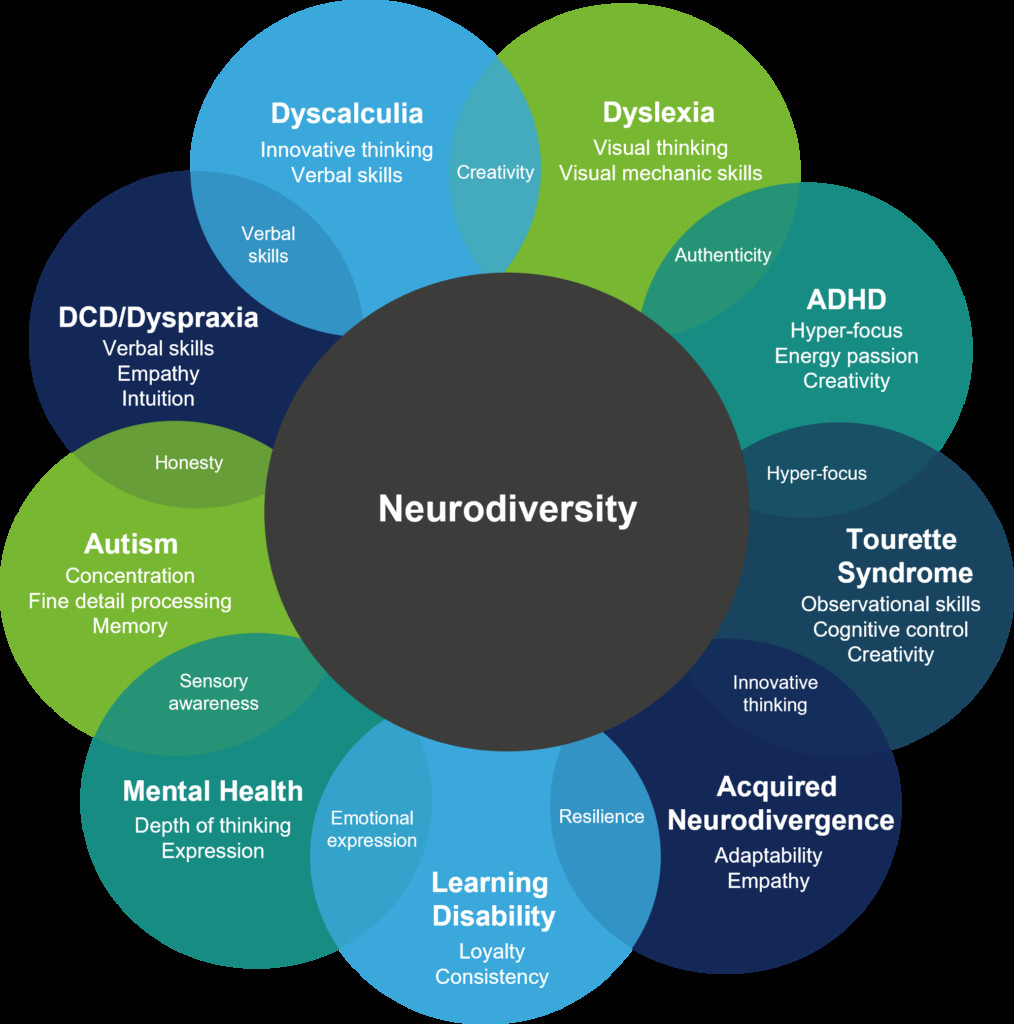

Neurodiversity refers to the variation in the human nervous system development, which may influence cognitive styles, emotional and sensory processing, mind-body connection, learning, and specific talents and abilities. Although originally discussed in the context of autism, the current understanding of neurodiversity refers to the full range of human neurological diversity. The broader understanding of neurodivergence refers to both developmental (such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and dyslexia) and acquired (such as post-traumatic stress disorder, brain trauma, and long COVID) differences.

Neurodivergent people find it extremely difficult, damaging to their health, or impossible to conform to some of the culturally defined expectations of neuronormativity. In most Western societies, norms privilege extroversion, preference for busy and revved-up environments, and fast rather than thoughtful and deliberate communication.

Neurological types characterized by differences that are inborn in tandem with facing stigma and prejudice because of the differences are referred to as neurominority groups. Currently, stigma and organizational barriers cause high levels of unemployment of highly qualified and highly educated neurodivergent talent, exacerbated by the lack of representation in leadership positions, resulting in the lack of advocacy for inclusion.

Neurominority individuals often have “spiky” ability profiles, characterized by areas of remarkable performance that coexist with areas of significant difficulty, similar to the spikes (or peaks) and valleys of a mountain range. That contrasts with the relatively flat ability profile of someone who is average.

For example, someone with a spiky profile may have a notable talent for understanding complex economic indicators and strategically capitalizing on them but will simultaneously have difficulty with day-to-day people management. Another person can be a master at building relationships but struggles with administrative paperwork.

Spiky profiles make matching work to abilities and strengths particularly important. According to JP Morgan, when matched to jobs with a focus on strengths, professionals with autism can outperform typical employees by 140 percent. Matching work to strengths is more effective than trying to remedy areas of struggle. Strengths-based staffing focused on specialist jobs and complementary strengths can aggregate to higher levels of organizational performance than generalist staffing, particularly in fast-changing environments.

Currently, despite their talents, neurodivergent business leaders and innovators face barriers due to stereotypes and outdated schemas of perceived talent norms that often privilege those who fit the image of an extremely confident, gregarious, charismatic individual. That bias can result in the advancement of people who are dangerously overconfident yet lack competence.

Meanwhile, hiring and promotion systems that traditionally privilege extroverted behavior and, more generally, neuronormative expectations, hold back highly competent neurodivergent people and may encourage turnover by creating the sense of not being valued and supported.

Many neurodivergent individuals use their talents to start their own companies, even if that was not their first choice. As one example, innovator Elon Musk, who has autism, stated that he became an entrepreneur because he could not get a job, citing shyness as a major obstacle.

And while entrepreneurship has its own set of challenges, some neurodivergent people left out of traditional workplaces achieve remarkable success, outcompeting organizations with a more traditional approach to leadership.

For instance, despite the stigma of dyslexia, business leaders with dyslexia, such as Richard Branson, have used their creativity to fuel exponential business growth and are overrepresented among self-made millionaires. According to the World Economic Forum, traditional corporations will be more competitive if they tap into the neurodivergent executive leadership talent pool and their unique cognitive abilities.

Stereotypes, misconceptions, and a one-size-fits-all approach to leadership development can sideline neurodivergent professionals or force them into roles poorly aligned with their talents. However, re-envisioning professional development pipelines can help such professionals lead in ways that bring out the best of their abilities and develop exceptional leadership teams where each individual can do what they do best.

Building an exceptional leadership team requires focusing on the unique, different strengths of individuals. There are no ideal leaders. In leadership selection, trade-offs exist among social energy, strategic thinking, understanding organizational processes, and industry-specific expertise. Companies can enrich the talent pool by developing multiple leadership tracks that cater to different strengths, interests, and ways of working.

For example, someone with exceptional strategic and analytical skills will thrive in a different leadership role than one that would fit a person who excels at developing and managing people or someone who enjoys improving internal processes. A leadership team of three people working in areas of their unique strengths is likely to be much more effective than a team of people with similar strengths profiles. In complex and dynamic environments that demand creativity, innovation, and contrarian thinking, drawing from a full range of human talent is vital for organizational survival.

Employers must expand the definitions of leadership to support a full range of helpful styles and qualities.

Recognize different leadership qualities. Traditional leadership models often emphasize charisma, confidence, and extroversion. It’s essential to recognize and value other qualities such as empathy, strategic thinking, attention to detail, and the ability to think outside the box. Those qualities are often strengths of neurodivergent individuals. In addition, contrary to the old assumptions about what makes a leader, when working with engaged, proactive teams, introverted leaders tend to be more effective.

Recognize nontraditional leadership contributions. Acknowledge and value leadership contributions that may fall outside traditional definitions, such as leading through innovation, enhancing team cohesion, or improving processes and efficiencies.

Redefine leadership roles. Consider creating leadership roles that capitalize on the strengths of neurodivergent individuals. For instance, roles focused on innovation, data analysis, or strategic planning can be ideal for those with strong analytical skills and a unique approach to problem solving.

Focus on leadership teams. Leadership consisting of clones cannot meet the challenges of a complex world. Focus on creating leadership teams with synergistic strengths that complement rather than duplicate each other.

Encouraging flexibility in leadership paths is about creating a career development ecosystem that acknowledges and supports the unique journey of every individual and the strength that comes from team diversity.

Effectively implement flexibility by using:

Customized leadership tracks. Instead of a singular path, develop multiple leadership tracks that cater to different strengths, interests, and ways of working. Allow employees to select or even design a leadership track that aligns with their strengths and career aspirations. Someone who is most comfortable with remote work may also be an excellent match for leading a remote, distributed team or an organization.

Skills-based advancement. Shift the focus from traditional promotions to skills-based advancement. Recognize and reward the acquisition of new skills and competencies that contribute to effective leadership, regardless of how long an individual has been in their current role. For example, a relatively junior employee who earned a specialized credential could lead a task group aligned with that area of expertise. That approach values growth and learning, offering a more accessible path to leadership that also ensures a well-qualified leadership team.

Mentoring and networking are essential components of leadership development, but traditional approaches can perpetuate biases that favor neurotypical behaviors and pressure individuals to conform to neurotypical standards rather than develop their unique strengths. Neuroinclusive leadership development calls for making mentoring and networking more neuroaffirming—honoring and leveraging neurodivergent abilities. Adjust the strategies and environments associated with programs to reflect the focus on making leadership pathways more neuroinclusive.

Neuroaffirming mentoring approaches include:

Neurodivergent mentors. Ideally, involve neurodivergent mentors because neurodivergent individuals can feel more at ease sharing experiences and challenges with colleagues who understand their lived experience. Recruiting neurodivergent mentors may call for creating disclosure safety to encourage potential senior mentors to volunteer. Support peer mentoring networks.

Neuroinclusion training for mentors. All mentors can benefit from training on best practices. Understanding the wide range of neurological diversity may help mentors avoid reliance on one-size-fits-all approaches. In addition, bias awareness can help prevent misinterpretations of neurodivergent behaviors and communication styles and ensure that mentors support their mentees effectively.

Strengths-based mentoring. Focus on developing a mentee’s strengths rather than forcing them to conform to neurotypical standards. Encourage mentees to develop in areas where they naturally excel and to find ways to leverage these strengths in leadership roles.

Inclusive networking opportunities can include:

Diverse networking formats. Traditional networking events often favor extroverts and take place in crowded, noisy environments that make them inaccessible for people with sensory sensitivities. Neuroinclusive networking calls for varied formats such as smaller, more intimate gatherings; online forums; or interest-based groups with a less overstimulating environment.

Structured networking. Organize networking events with clear agendas, such as one centered around a learning topic. For many neurodivergent people, a predictable structure can help them to engage more effectively.

Use technology. Applications and platforms that enable people to connect and communicate in different ways can help create networks based on shared interests or specific needs.

TD practitioners are uniquely positioned to foster environments where all employees can thrive and contribute to their full potential. By expanding definitions of leadership and promoting flexibility in leadership paths, organizations can support the career progression of neurodivergent talent and benefit from a more diverse and innovative leadership team. Such flexible career paths can help build a more inclusive, adaptable, and resilient company.