The promising new test is better at detecting Alzheimer’s disease than physicians—but experts don’t recommend it for everyone.

Demonstrating that someone has Alzheimer’s is currently invasive and expensive. But one day, a simple blood test could make diagnosis faster and easier.

For years, scientists have worked to develop methods to detect evidence of Alzheimer’s in the blood stream, and a new test described on July 28 in the Journal of the American Medical Association and presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Philadelphia proved better at diagnosing the disease than the average physicians. While the tool isn’t currently recommended to screen for the disease before symptoms emerge, it could expnd access to testing.

“The results of this study are striking and very promising,” says neurochemist Inge Verberk of the Amsterdam University Medical Centers in the Netherlands. “Having a blood test available in primary care might result in less diagnostic delay and earlier initiation of treatment. More effective diagnosis might also reduce waiting times before people can visit a specialized neurologist.”

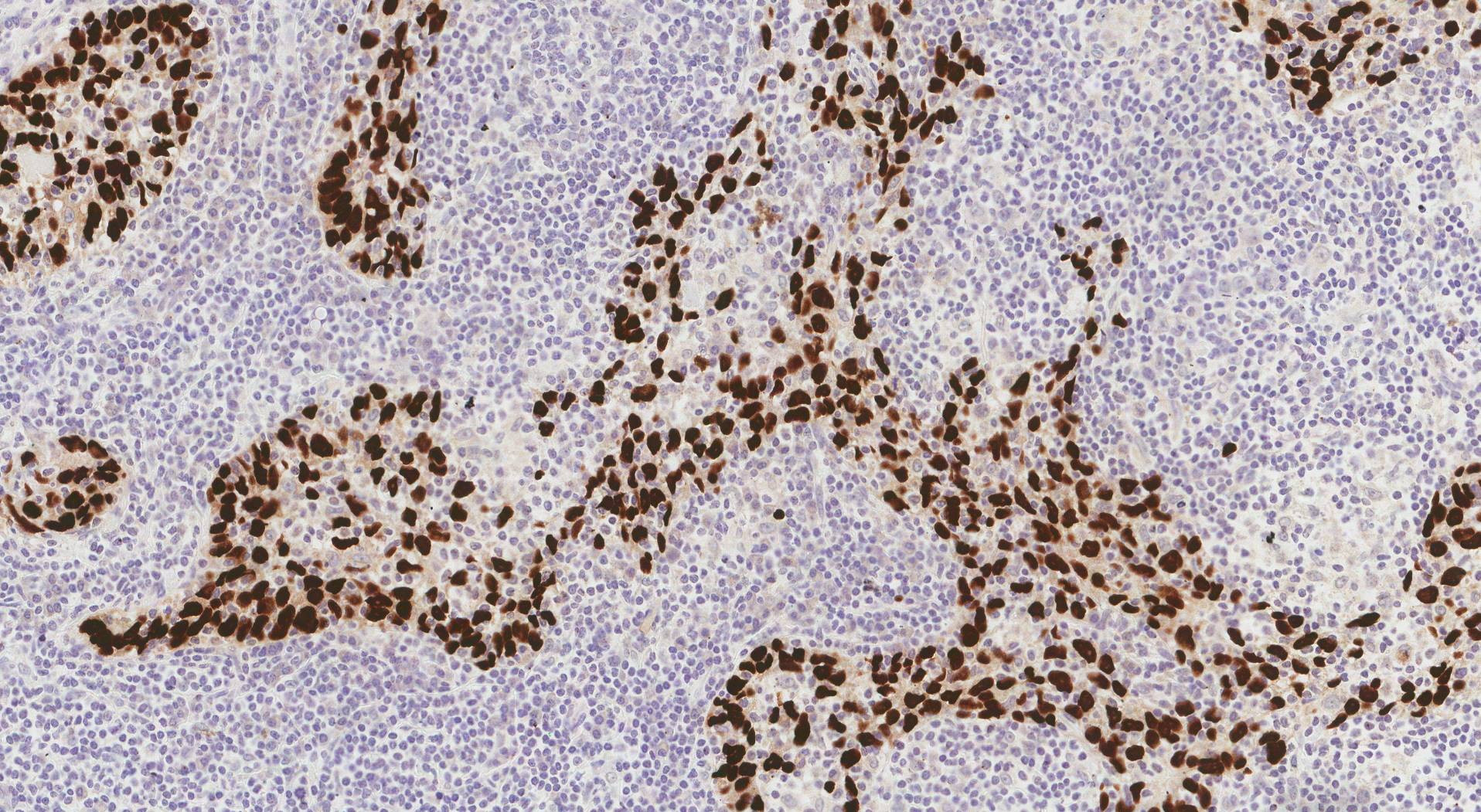

Identifying Alzheimer’s in a patient hinges on two proteins typically found in the brains of people suffering from the disease: modified forms of amyloid-beta, which clump into plaques, and tau, which entwine into tangles. Both are associated with a higher risk of developing dementia. Around the turn of this century, the presence of these plaques and tangles could only be established after death, by dissecting a patient’s brain.

In the mid-2000s, scientists figured out how to detect these proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid that courses through our central nervous system and can only be extracted via spinal tap. This involves inserting a needle into the spinal cord, however, which can be rather painful and is not entirely without risk. Today, clinicians can also detect amyloid-beta and tau on brain scans. But this requires injecting radioactive compounds into the blood stream, as well as expensive equipment. So better diagnostic tools are sorely needed.

The new test compares the blood levels of two types of amyloid-beta and two types of tau. These ratios give researchers a sense of the risk of protein plaques and tangles in the brain.

For this study, researchers compared the ability of healthcare practitioners to identify Alzheimer’s patients in Sweden with that of the new test. Primary care physicians in the study correctly identified only 6 out of 10 patients that were later revealed to have Alzheimer’s by spinal tap or a PET scan of the brain. Dementia specialists did just slightly better, identifying 7 out of 10. Yet the new blood test provided a correct diagnosis for 9 out of 10 patients.

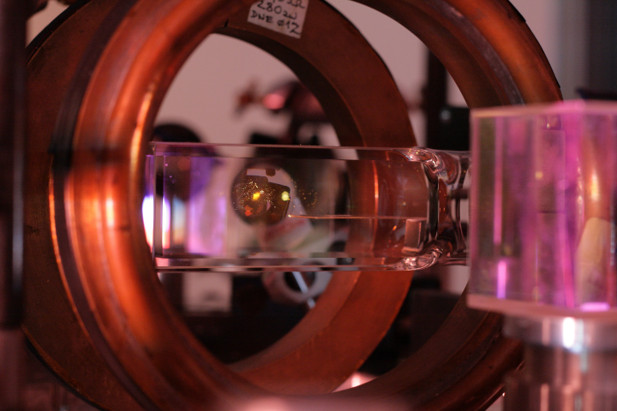

Some obstacles remain, though. The test requires an advanced method known as mass spectrometry, which involves advanced equipment and requires the blood to be stored at -80°C. All the blood samples also had to be transported for analysis from Sweden to the U.S. company that conducted the test. Implementing this test might therefore not be as easy or inexpensive as it sounds, but the Swedish study does provide proof of principle that blood tests can be useful, low-threshold methods for accurate diagnosis, especially if the samples could be analyzed in a less exacting way.

Thankfully, this isn’t the only Alzheimer’s blood test on the horizon. Various studies on different blood tests were presented at the meeting, says Rebecca Edelmayer, the Alzheimer’s Association’s vice president of scientific engagement. “In the relatively near future, blood tests may significantly improve the accuracy of diagnosis. However, the implementation must be done in a careful and controlled way, and much more research is needed. At this time, these tests are not recommended for general population risk screening or as direct-to-consumer tests.”

Some of these other blood tests “are as good as the mass spectrometry test,” says Michelle Mielke, an epidemiologist at Wake Forest University. She adds that blood tests are not recommended for people without symptoms, even if they have a family history of Alzheimer’s disease, since “we do not currently understand what a positive test means for people without cognitive impairment.”

Gemma Salvadó, a clinical neuroscientist at Lund University in Sweden and a senior author on the study, agrees. “We don’t currently recommend this test for people who are not cognitively impaired,” she says, referring to patients who don’t score within the Alzheimer’s range on tests designed to gauge the functioning of their brain. “And this test should always be done together with a specialist like a neurologist or a geriatrician, someone who understands what the results mean in the context of a specific patient.”

The test compares the blood levels of regular tau and a modified form called p-tau217 that appears quite early in the disease process and keeps increasing in concentration as the disease progresses. This is because in some patients, for example those with certain kidney disorders, the levels of all proteins in the blood are generally higher, explains Salvadó. “So a higher level of p-tau217 as such does not necessarily indicate they may have Alzheimer’s.” For the same reason, the test also compares the blood concentration of two different kinds of amyloid-beta.

The ability to check for amyloid-beta and tau using a blood test might allow testing in populations that have no access to testing today, says Salvadó, especially if similar tests that are easier to use and more widely available would also be shown to be effective. It would also help researchers in resource-limited countries conduct studies in areas where little Alzheimer’s research has been done.

While these findings are promising, some caution is warranted, says Chi Udeh-Momoh a neuroscientist at the Global Brain Health Institute. “Tests like these have been almost exclusively developed in Western populations, and primarily in high-income settings. So their applicability to other demographics remains uncertain, particularly those with different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

The participants in the Swedish study were quite diverse in terms of their other health problems, education level and whether they lived in the city or in rural areas, all of which may have an effect on Alzheimer’s risk, but the ethnic diversity was low. This means extrapolating to the more diverse population of the U.S. might be difficult, says economic epidemiologist Emmanuel Drabo of Johns Hopkins University. “The percentage of p-tau217 may have different implications for different groups.” So as encouraging as this initial study might be, it will be important to repeat it elsewhere.

Beyond diagnosis, the blood test may also help doctors determine which patients might benefit from different types of treatment. Most current treatments for Alzheimer’s just manage symptoms, but two recently developed antibodies that target amyloid-beta can slightly delay disease progression. These drugs only slow cognitive decline by a few months, however, and come with a risk of side effects like swelling and bleeding in the brain that requires advance genetic testing as well as regular MRI scans to ensure safety.

Even in the absence of effective treatment, more easily accessible information is important, says Salvadó, as more efficient testing could give patients more time to process and prepare. “It allows patients and their families to plan for the future before they’re too disabled,” she says.

If medication that can significantly slow down, halt or reverse the disease does emerge from ongoing research efforts, testing may become crucial, says Salvadó. “I think heart disease is a good analogy: you can easily measure cholesterol levels in the blood, even in the absence of symptoms. And if levels are too high, you can start a diet or take a pill. Perhaps in the future, the accumulation of amyloid-beta and tau in the brain can be tested and treated like high cholesterol. But these are very early days.”

Research has given us a more in-depth understanding of Alzheimer’s disease in recent years. It’s now known that there are biological changes linked to the condition. This new and advanced knowledge has led to new treatment options, as well as revised diagnostic criteria. In June 2024, an Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup released revised criteria for the diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease that incorporates recent research developments.

The updated criteria includes an advanced biomarker classification system using blood-based markers. These biomarkers are grouped into three categories: core biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathic change (ADNCP), non-specific biomarkers that are important in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and also seen in multiple degenerative brain conditions, and biomarkers of common Alzheimer’s comorbidities.

There are two subtypes of biomarkers within the core biomarkers. Core 1 biomarkers measure the buildup of amyloid plaques or phosphorylated tau. Core 1 biomarkers change early in the disease course. Core 2 biomarkers can help provide prognostic information; they measure deposits of aggregated tau in the brain and appear later in the disease course.

According to the most recent Alzheimer’s research, changes to Core 1 biomarkers begin before symptoms of the condition are presented. The progression of changes to biomarkers leads to the presentation and progression of expected Alzheimer’s symptoms, including memory loss and cognitive difficulty. In its revised diagnostic standards, the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup concluded that the presence of these blood-based biomarkers can be sufficient to diagnose Alzheimer’s: “AD is defined by its unique neuropathologic findings; therefore, detection of AD neuropathologic change by biomarkers is equivalent to diagnosing the disease.”

Currently available Alzheimer’s treatments provide symptom relief but do not slow down disease progression. Emerging treatments aim to change this by targeting biological factors. For instance, as of July 2024, three anti-amyloid immunotherapy treatments have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Diagnostic results showing the buildup of amyloid plaque, a Core 1 biomarker, are essential for the use of these drugs.

Neuroradiologist Clifford R. Jack, Jr., MD, Professor of Radiology at the Mayo Clinic and a lead author of the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup’s new criteria, explains: “These updates to the diagnostic criteria are needed now because we know more about the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s, and we are able to measure those changes. Treatments that target one of these processes have been approved by regulators, and biomarker proof that the underlying biology is present must be confirmed to be eligible for treatment.”

Additionally, traditional symptom-based diagnostic criteria can overlap with other neurologic disorders and conditions. Biomarker testing has the potential to allow for a more definitive diagnosis.

The revised criteria aren’t intended to be used as a formal guideline for clinicians. The Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup emphasizes that clinical judgment is still key to diagnosing Alzheimer’s. Although findings show that Core 1 biomarkers change before symptoms are present, researchers are not currently recommending biomarker testing for asymptomatic individuals.

The Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup writes, “The biologically based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is meant to assist rather than supplant the clinical evaluation of individuals with cognitive impairment.”

Some healthcare experts have raised concerns about new diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s. For instance, in 2023, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) published a response to earlier suggestions made by the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup about biomarker-based diagnostics. In its response, the AGS expressed hesitation about diagnosing asymptomatic individuals with Alzheimer’s, writing, “AGS is concerned about the rationale of making Core 1 biomarkers the basis for clinical diagnosis or labeling all people with amyloid biomarkers as ‘having AD.’ Such action ignores decades of social science research on the often-adverse effects of labeling, including promotion of stigma, and begs the question as to what purposes biomarker-based diagnosis might serve in patient care.”

It’s been stated that biomarker testing has the potential to help with early detection and treatment of Alzheimer’s. At this time, however, biomarker testing isn’t being used to diagnose individuals without symptoms. The AGS, the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup, and other leading organizations agree that further research and clinical testing is vital.

The diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s are shifting. Clinical judgment, including an assessment of symptoms, is still crucial, but an understanding of the biological factors that lead to Alzheimer’s plays an increasingly important role in disease diagnosis and treatment. The Alzheimer’s Association has stated that it will begin working on guidelines around the clinical implementation of Alzheimer’s disease staging criteria and treatment later this year.