Phil Lesh, bassist and founding member of the Grateful Dead, died Friday at the age of 84. A brief statement on his official Instagram account said Lesh died “surrounded by his family and full of love.” The post did not cite a specific cause of death. Lesh had previously survived bouts of prostate cancer, bladder cancer and a 1998 liver transplant necessitated by the debilitating effects of a hepatitis C infection and years of heavy drinking. “Phil brought immense joy to everyone around him and leaves behind a legacy of music and love. We request that you respect the Lesh family’s privacy at this time,” the post read.

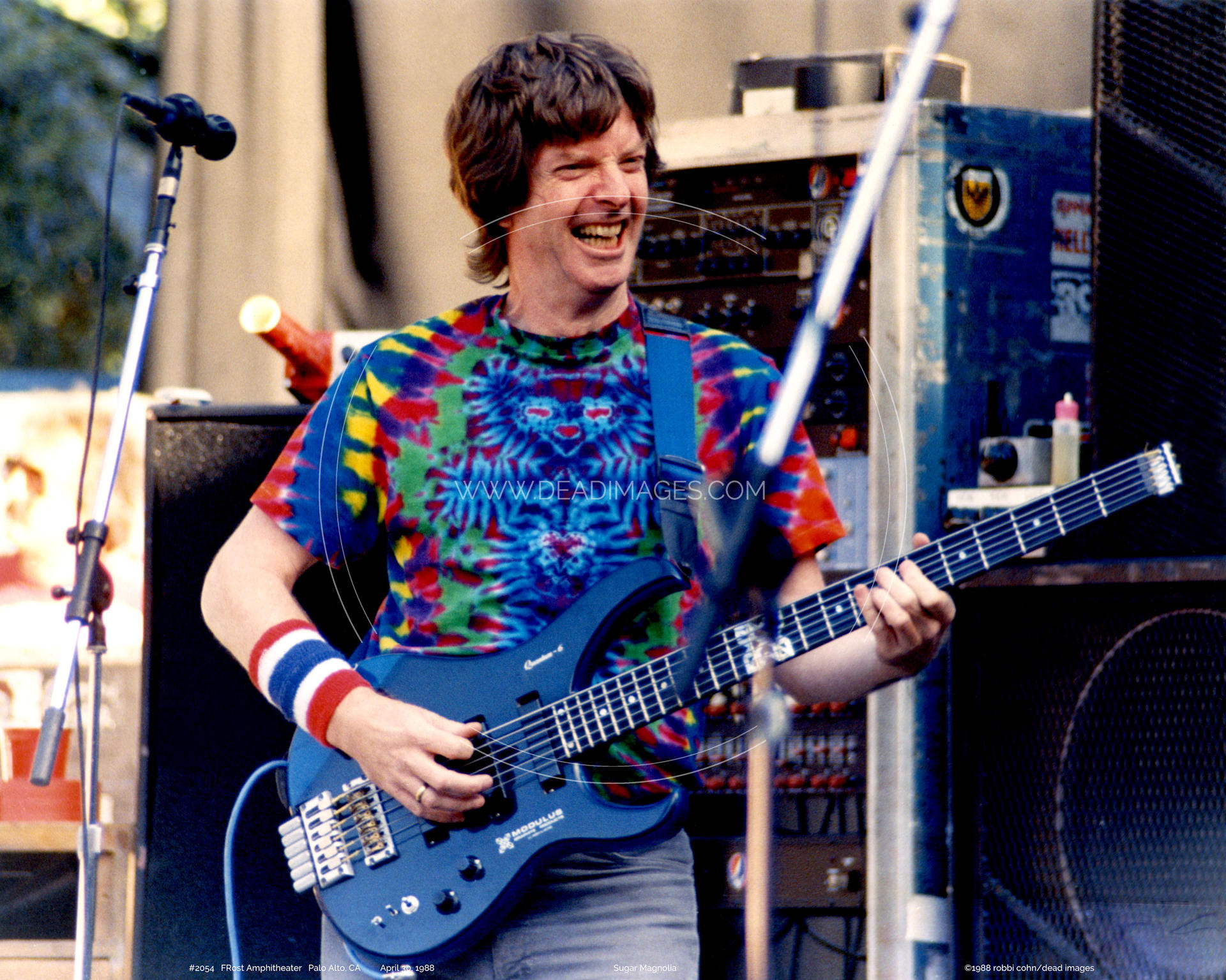

Lesh, a Berkeley, California native, helped form the Grateful Dead in the San Francisco Bay area with lead guitarist and vocalist Jerry Garcia, rhythm guitarist and singer Bob Weir and drummer Bill Kreutzman in 1964. He quickly became known for his unconventional style of bass playing, which was inspired by his background in classical music and jazz and helped define the Dead’s unmistakable sound. With the support of legions of “Deadheads” across the U.S. and around the globe, the Grateful Dead toured relentlessly for 30 years.

Following the band’s disbandment in 1995 after the death of lead guitarist Jerry Garcia, Lesh continued to make music, forming groups like Phil Lesh and Friends, a rotating lineup that featured many prominent musicians. In 1998, Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, Mickey Hart, and Bill Kreutzmann began performing together as The Other Ones and later as The Dead, bringing Grateful Dead music to fans while exploring new material. He did take part in a 2009 Dead tour and again in 2015 for a handful of “Fare Thee Well” concerts, marking both the band’s 50th anniversary and what Lesh said would be the last time he would play with the others. He did continue to play frequently, however, with Phil Lesh and Friends.

In later years, he usually held those performances at Terrapin Crossroads, a restaurant and nightclub he opened near his Northern California home in 2012. The club was named after the Grateful Dead song and album “Terrapin Station.” Lesh is survived by his wife, Jill, and sons Brian and Grahame. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

This past Friday, the bassist of The Grateful Dead, Phil Lesh, passed away at age 84. Almost immediately the tributes poured in, most recognizing that Lesh wasn’t your ordinary bassist. As Jon Pareles wrote in the New York Times, Phil Lesh held songs “aloft.” His “bass lines hopped and bubbled and constantly conversed with the guitars of Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir. His tone was rounded and unassertive while he eased his way into the counterpoint, almost as if he were thinking aloud. [His] playing was essential to the Dead’s particular gravity-defying lilt, sharing a collective mode of rock momentum that was teasing and probing, never bluntly coercive.”

When others try to capture what made Phil, Phil, they’ll feature another beloved show–Veneta, OR (6/27/72). Below, you can hear isolated tracks of Phil’s bass work on “Bertha” and “China Cat Sunflower/I Know You Rider.” (Click the links in the prior sentence to hear Lesh and the band performing the songs together–so you can hear how the bass ties in.) Trained in free jazz and avant-garde classical music, Lesh infused rock with the influences of Coltrane, Mingus, and Stravinsky–not to mention others. And, with that, the bass was never the same.

For anyone wanting to get further into the Phil Zone, read his excellent memoir Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead.

When Grateful Dead co-founder, bassist, sometime backing vocalist, and eternal experimenter Phil Lesh died on Friday at the age of 84, Deadheads were keen to let you know he wasn’t just some guy in the group. Lesh, whose roots were in the avant-garde, was one of the first musicians in rock music to play the bass as though it were a lead instrument — ironic in that he was trained in violin, trumpet, and modern classical composition before Jerry Garcia asked him to join the pre-Dead band the Warlocks and fill that position. With lead guitarist Garcia and rhythm guitarist Bob Weir, Lesh was the bottom layer in an unpredictable rush of sound. Add in keyboards, a drummer, a second more far-out drummer, Donna Jean Godchaux screaming “yeaaaaahhhhh!,” and a lot of other mayhem, and you start to understand what made the Grateful Dead special. It was a big stew, and Phil Lesh was a main ingredient.

After Garcia died in 1995, Lesh played with several post-Dead bands as well as his own evolving group, Phil Lesh and Friends, which, by the end, featured up-and-comers on the scene often 50 years his junior. Recently, he began posting “clubhouse sessions” to YouTube with a rotating door of younger players, including a series called Darkstarthon that used the signature Dead exploration jam “Dark Star” as a launching point.

Bass-playing in a rock context is oftentimes the lone bastion of conservatism: Just keep the beat. Lesh’s mission statement rejected that. “The fervent belief we shared then, and that perseveres today, is that the energy liberated by this creation of music and ecstatic dancing is somehow making the world better,” he wrote in his 2005 memoir Searching For the Sound, “or at least holding the line against depredations of entropy and ignorance.” Lesh spent his entire career holding that line, and these ten tracks showcase how.

Let’s dive right into the deep end. “The Other One” is a quintessential early Grateful Dead jam that never left their set list. Frequently emerging from the free-form percussion exercise “Drums,” it begins with a loping Lesh fanfare before the band crashes in. The Frankfurt ’72 show is a perfect example of the Dead’s triple layer, with Garcia dervishing up top, Lesh worming down low, and Weir feeding them both with irregular rhythms and chords. This is a half-hour exploration that jazzes its way into atonal space, but Lesh never loses the groove.

If “The Other One” is trial by fire, this is a much more agreeable entry into the Grateful Dead and their only mainstream radio smash. It might be pop, but it’s still a great song, with clever lyrics, a sing-along chorus, and a perfect (albeit short) Garcia guitar solo. And what’s the first thing you hear when the tune fades in? Phil Lesh bah-bum-bah-bum-ing along. For a regular pop song, that’s all the bass player would do. But by the 20-second mark, Lesh is doing his typical galloping runs under the melody and coming out during rests in the chorus for some giddy yap fills.

Lesh did not write and sing lead vocals on many Grateful Dead songs, but when he did, it was a knockout. “Box of Rain,” which he composed for his dying father, is a gorgeous, melancholy melody with complex chord changes. Opening the Dead’s fifth studio album, American Beauty, it marked a turn from the more experimental material in the studio (Phil’s forte). But he sure put his stamp on the transition.

In Searching for the Sound, Lesh wrote that his fondest musical memories of the Grateful Dead remained the early days, when Ron “Pigpen” McKernan would come out from behind the keyboards and strut around to a psychedelic version of an R&B classic, like “Big Boss Man” or “Turn on Your Lovelight.” (Lesh called these “rave-ups.”) But the best for jamming — and for Lesh — was “Hard to Handle.” For his Fallout From the Phil Zone collection, Phil selected the August 16, 1971, version from the Hollywood Palladium, but I have to speak my truth: Just a few weeks earlier — at Yale, of all places — the band laid down the best “Hard to Handle” in history. If Phil’s thunga-thunga-thung riff doesn’t get you moving, check your pulse, because you might be dead.

This is another of the rare Lesh-on-lead-vocals tracks, but unlike the anthemic “Box of Rain,” “Unbroken Chain” makes you work for it. (Indeed, the phrase “searching for the sound,” which Lesh borrowed for his memoir, comes from this tune.) The song starts with an unusual guitar filter and some deep bass strides, then continues with harmonies from Godchaux, a time-signature change, and Ned Lagin’s synthesizers. Though a “mellow tune,” everyone — especially Lesh down low — is keeping busy, proving that when Lesh presented something to his bandmates, it was never dashed-off.

A Lesh composition, “The Eleven” gets its name from its tricky 11/8 time signature. This February 1969 rendition is a tremendous showcase for his bass running like a jackrabbit just as frantically as Garcia’s lead guitar or the four-armed drumming of Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart. Even the Lesh-less post-Dead group Dead & Co., which tends to keep things super mellow, kicks it into a higher gear when they bust this out.

In ’77 and ’78, the Dead turned up the funk, and some naysayers turned their back on what they derogatorily called “Disco Dead.” Either way, this era is certainly bass-heavy, and while there is an entire shelf of Dead literature calling May 8, 1977’s “Scarlet > Fire” from Ithaca the period’s apex, I have a fondness for this “The Music Never Stopped” from a few weeks later, especially since you can really hear how Phil takes a simple “disco” bass line and curves it, bends it, and slaps it around.

“Dark Star,” which the entire band created, is the blank canvas, no-two-versions-slightly-the-same communion with inner and outer space that was most likely to send Heads into epiphanic euphoria (or the occasional bad trip). Attending a Dead show was already entering a special club, but getting a “Dark Star” was entry to the VIP section. I can’t really select a specific “Dark Star” for this list (that’s too personal, man!). Instead, check out “Grayfolded,” initiated by Lesh, in which decades’ worth of “Dark Stars” were mixed and blended and baked into a whole new composition. This one section called “The Phil Zone,” where you’ll hear Lesh strumming the bass, plunking harmonics, and launching arcs of feedback, reveals his kid-in-the-candy-store side amid all his high-tech gear and seems like the appropriate sampling.

Among those who saluted Lesh at his passing was jazz saxophonist Branford Marsalis, who played with the Dead at a handful of gigs over the years. The high point is this 16-minute version of “Eyes of the World.” Lesh’s bass explorations are unceasing while Marsalis and Garcia trade solos, and Brent Mydland slots in his perfectly glassy electric-piano tones.

This may sound like a joke, but if you want to know what makes Lesh different, look to “Donor Rap.” He received a liver transplant in 1998 from a man named Cody, and Lesh soon cleared a moment in the set list to share his story. Cody had once told his mother that, if anything should happen to him, he wanted his organs donated. Lesh then encouraged audience members to do the same. Tapers began putting “Donor Rap” on show recordings, and official releases and streams list the little chat as its own track. Heads being Heads, you can go to Reddit to find rankings for best versions of “Donor Rap,” the highest form of flattery from this fandom.

JTA — Among the legions of Grateful Dead fans mourning Phil Lesh are a small but devoted cohort of Jewish Deadheads with memories of celebrating Passover with him. “To life! To Phil! Our love will not fade away! Eternally grateful,” the Jewish vocalist Jeannette Ferber posted on Facebook, alongside a picture showing herself with Lesh at a Seder. Lesh, the legendary jam band’s bassist, died Friday at 84. His Instagram account, which announced his death without specifying a cause, said Lesh was “surrounded by his family and full of love” and “leaves behind a legacy of music of love.”

That legacy includes facilitating musical Jewish holiday celebrations at Terrapin Crossroads, a restaurant and music venue that he operated with his wife in San Rafael, California, from 2011 until 2021. Lesh was not Jewish, but he was long aware of the large number of Jewish fans among the Grateful Dead’s devoted following and sought to create space for them in the community-oriented venue. “We want to honor all traditions of our fans — as what is community without its traditions and world view?” he told J. The Jewish News of Northern California in 2014, the year of the first Seder. After the Passover meal, which featured food donated by a deli owner and Deadhead, Lesh’s Terrapin Family Band played a two-hour set including covers of the spiritual “Go Down Moses” and Bob Marley’s “Exodus.”

Ferber, then the cantorial soloist at the Berkeley, California, Renewal congregation Chochmat HaLev, led most of the Seder, kicking off a recurring event that always ended with an extended set featuring Lesh and regularly sold out. “This is my family, and who I spend the most time with, so it makes sense that this is how I’d spend my Passover,” Brian Markovitz, who ran the deadheadland website as well as the Facebook group Jews for Jerry, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in 2016. “It’s so great that Phil recognizes that.”

The Seders drew on Lesh’s longtime ties to Jews and Jewish culture. Born in Berkeley in 1940, he was devoted to music from an early age and learned to play bass after being recruited by Jerry Garcia in 1964 to join a band that would become the Grateful Dead. The band’s big break came after the famed rock promoter Bill Graham, a child refugee from the Nazis whose mother was murdered at Auschwitz, booked a gig at the Fillmore San Francisco. Its members — including one Jew, Mickey Hart — continued to play together until Garcia’s death in 1995. Afterwards, Lesh performed with his own group, Phil Lesh and Friends.

Jewish affinity for the Grateful Dead has bordered on the religious, with Jewish Deadheads holding prayer and music retreats around the country. “Jews and the Dead relate in that we both wander,” a Deadhead from Jerusalem told JTA during a 2012 retreat at the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center in Connecticut. (Phish, the Grateful Dead’s present-day successor, is similarly entwined with Jewish cultural and religious identity, according to a recent scholarly book; Lesh performed with his former Grateful Dead bandmates for the last time in a joint concert with Phish.)

The fan group behind the Seders has continued coming together for holidays, including most recently for a Sukkot concert last week. For Lesh, who is survived by his wife and two sons, the Seders were meaningful events that he returned to even when he was no longer needed to host. “Who knew you could have so much fun at a Seder?” he asked at the first Seder in 2014. “Words fail me.” In 2020, with Terrapin Crossroads closed because of the pandemic, he joined a group of diehards at a virtual Seder. “I wouldn’t miss this for anything,” he said.