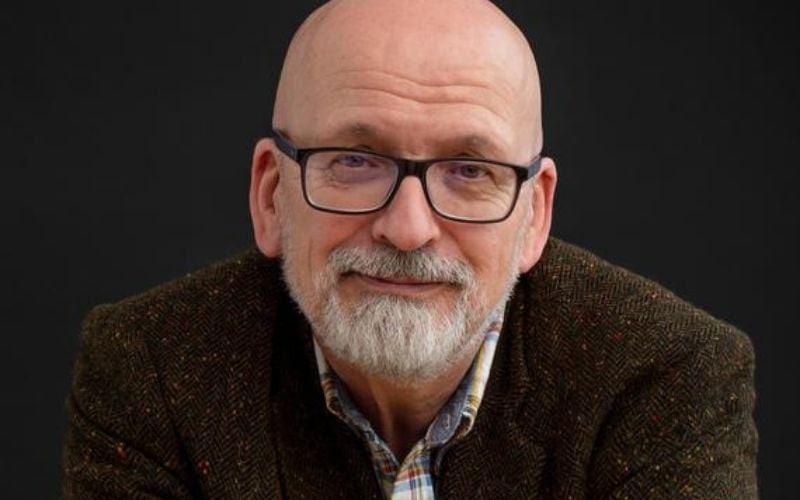

It’s Roddy Doyle’s first time in the lovely basement cafe at MoLI, the Museum of Literature Ireland, on St Stephen’s Green. Even more surprisingly, for one of Ireland’s most prolific writers, he has only been upstairs in the actual museum once before. “I’m not dead,” he smiles, by way of explanation.

Definitely not dead, but Doyle does appear extremely relaxed after several weeks on holiday during which, by all accounts, he got up to very little. “Some days I’d go for a long walk and other days I just deliberately did nothing. Like I didn’t go anywhere, I didn’t listen to a podcast, I didn’t listen to music, which was weird. I just wanted to turn it all off and I was perfectly content.” If it sounds like he was indulging in a bit of mindfulness, nothing could be further from the truth. “If anything it was mindlessness, not mindfulness. I don’t buy into any of that shite.”

Today is his first day back at work. We’re here to talk about The Woman Behind the Door, and Paula Spencer, the woman he’s been writing about for three decades. This is his 13th novel. His first, The Commitments, was famously self-published in 1987 and later made into a movie by Alan Parker. Since then he has been one of the most consistent and wittiest voices of working-class Dublin with books such as The Snapper and The Van. In 1993, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha landed him the Booker Prize. He has written books and plays for children including The Giggler Treatment and Greyhound of a Girl as well as historical novels for adults such as A Star Called Henry. He has delved into nonfiction with a book about his late parents, Rory and Ita, and biographies of Kellie Harrington and Roy Keane. He now counts those sporting giants as friends.

This latest instalment of Paula Spencer’s life is set in the pandemic, with our resilient heroine now 10 years sober, living alone, with a job in a dry cleaner’s, some great friends and a romantic partner, Joe. A lot has changed but much is the same. The ghost of Charlo, her abusive husband, still hovers and she remains smothered by the guilt and shame of what her four, now grown-up, children had to witness in their violent, dysfunctional home.

It’s a confident, maybe even courageous, writer who decides to use the recent pandemic as a backdrop to a novel. There’s the risk that readers might not want to be returned, even in a fictional sense, to the world of restrictions, face masks and fear. Such concerns didn’t bother Doyle – “it’s neither here nor there”. He was getting his first vaccine on stage in the Helix theatre on the DCU campus in 2021 when his mind wandered again to Paula Spencer. The Helix was an interesting place to be vaccinated, both for local audiences who had seen pantomimes there but in particular for Doyle, who has had his own work shown on that stage. Driving home he thought of Paula, abused wife, recovering alcoholic, survivor, mother, now grandmother, a woman he first wrote about 30 years ago as part of the groundbreaking, four-part television series Family.

Last spring, Doyle wrote about the fallout from Family in an essay for this publication. The series, especially the episodes focusing on Charlo and Paula, laid bare the stark reality of domestic violence – “spoke it out loud”, as Doyle says. There was praise at the time for the authenticity of the writing but Doyle also got hate mail and death threats. His mother was pushed in the street. There were church sermons saying he was “undermining the family”, he remembers.

“I’d managed to live a quiet, private life up until then, but suddenly going to the shops was a big decision.” It wasn’t all bad. After winning the Booker the year before and having just had the TV version of the Snapper broadcast to universal and enduring acclaim, he had been getting invites from all comers to open this, or speak at that or unveil the other. All those invites dried up, “which was great”.

Not so positive was an experience with a girls’ secondary school in Roscommon where the students voted for which writer they would most like to see visit and give a talk. The girls voted for Doyle. “When I got to the school I was told by a nun that some parents had objected and the invite had been withdrawn. I’d driven from Dublin, so it was annoying, but more than that it was hurtful.”

None of this stopped him from delving further into Paula Spencer’s story. Family was followed in 1996 by The Woman Who Walked into Doors, which explored Paula’s back story and her life with terrifying Charlo. Ten years later the novel Paula Spencer gave us a Paula-eyed view of the Celtic Tiger. In The Women Behind the Door we meet Paula returning home fresh from her Covid jab in the Helix. That “great day” included an al-fresco McDonald’s down at Dollymount Strand, bending the Covid restrictions with her mates.

She muses that she was already prepared for lockdown, having lived with restrictions for years as a recovering alcoholic and an abused wife. She says the vaccination made her elated, like after sex, “floating on the afters of the orgasm”. Her 72-year-old lover, Guardian-reading Joe, is the kind of person who knows the Japanese word for the mental state of a man immediately after orgasm. Doyle doesn’t put the word in the book but I look it up and discover that Kenjatimu means “a period of clear thoughts when a man is free from sexual desire after having an orgasm”. Paula may be in her 60s but Doyle gives her a vivid sexual identity, even if it has been curtailed by Covid.

So life is relatively stable for one of Doyle’s most beloved characters when her menopausal eldest child, Nicola, arrives at the house depressed and in the grips of a breakdown declaring she wants out of the ostensibly happy and successful life she has built with her husband and three daughters. In order to buy time to unravel her daughter’s predicament, Paula comes up with the “genius” lie of pretending they both have Covid so they have to spend two weeks locked down together. “I don’t usually attach too much importance to plot; there’s rarely a twist,” says Doyle of his books. But having the two women locked down together was “the best thing”.

Doyle has been described as “the undisputed laureate of ordinary lives” and nowhere is that illustrated more in his work than with Paula Spencer. He shares this ability to elevate the ordinary with writers such as Elizabeth Strout. Is he a fan? “Very much so, yes.” With this new book, he’s examining Paula’s life in the aftermath of all she’s been through. “Despite all the circumstances of her life, is her life worth living? Yeah. Why is it worth living? She has her grandchildren, she has her children, she knows they are well, that they are all, in some shape or form, coping even if it’s not the way she would have hoped when she was a young woman. But she also has her friends.” Friendship is a huge motif in the book, from supportive text messages to food parcels left at the door when Paula and Nicola are enduring their self-enforced lockdown.

The Covid pretence is a device that allows mother and daughter to be thrown together, for secrets to unspool and ugly truths to be spoken. In this way, Paula gets a chance to mother Nicola in a way she hasn’t before, bringing her food, lying next to her in one of her son’s childhood bedrooms, listening closely as gradually the reasons for her daughter’s breakdown are revealed.

There are harsh words, black humour, a lot of screaming and a powerful mother-and-daughter reckoning. Key to it all is the memorable moment near the end of The Woman Who Walked into Doors when Paula whacks Charlo with the frying pan and finally throws him out of the house for good. That morning she had seen Charlo looking at Nicola with hate in his eyes which prompted the attack. “She [Paula] stops being a battered wife when she becomes a protective mother,” as the rave review in the New York Times put it back in 1996.

In the new book, 30 years later, Paula has reframed this event in a significant way. She tells Nicola that the look Charlo gave her daughter that morning was “inappropriate”. She has come to realise that it was desire she had seen in Charlo’s eyes, and that was what made her fingers reach for the frying pan. Now Paula has to confront all of this from Nicola’s perspective, which proves seismic for both women.

“I think I always had a grip on the psychology, and the thing about psychology is that our inner workings always reveal something new, and they always make nonsense of our previous conclusions,” says Doyle. We talk about the word “inappropriate”, the word Paula uses, carefully, to describe the way Charlo was looking at her daughter. “These days, four- or five-year-olds know the word ‘inappropriate’, but nobody used the word back then ... It can take a long time for the right word to drop, the word to describe what you saw exactly. What seemed normal or a rite of passage or even funny is awful to us now.”

He has personal experience of this, as so many do. He talks about one Christian brother he was aware of who “regularly took boys away to bring them into a classroom to teach them ‘wrestling’. We didn’t have the words to describe what was going on. We didn’t have the vocabulary other than making a joke about it, which is what we did.” He says this teacher chose his victims well.

The novel is dripping with guilt and intergenerational trauma. “The real damage,” says Paula, “is that she can’t face her children, not even in her imagination. They’re like a jury and she’s always guilty – she knows she’s guilty. Nothing will ever make her know or feel any different.” And elsewhere she says: “Guilt that’s what Charlo had left her. The family jewellery. A necklace, pearls of jet-black guilt. Choking her.”

Paula Spencer and Roddy Doyle are almost exactly the same age. “I think she has nine months on me,” he says, when I bring it up. This age similarity is no accident. Doyle vividly remembers sitting down to write The Woman Who Walked into Doors because it was his first book as a professional writer, having given up his teaching job in Greendale Community School after winning the Booker. “I felt on thin ice [writing Paula], because even though I’d got to know her through Family, I was still trying to see through her eyes. I made her my age so I could share her soundtrack, the music; the dance hall where she met Charlo was one I’d been to. It was a way of seeing over her shoulder as she was walking around.”

As a man, did he ever have any trepidation about returning to write about Paula Spencer, given recent conversations in publishing about who gets to write certain stories? “No,” he says immediately. “The only conversation I had with myself was, ‘Is this accurate? Is it good enough?’ and I’d have that about every character I write. I think the notion that a writer can’t write about certain things is a nonsense.”

Doyle is now deep into his 14th novel, a book set in the 1980s with a young male teacher as narrator. He’s never properly explored his own teaching experiences through fiction. So why teaching, why now? “Because there’s so much of me in it. I wouldn’t have written The Commitments if I hadn’t been a teacher. It has always fed me creatively, even to this day.”

As an observer of Dublin and Irish life through his fiction, how does he feel about the state of the country now, in particular with the rise of right-wing, anti-immigration activity? “Generally I feel quite good about living in Ireland,” he says. “I think we were probably a bit smug for a while, thinking we were untouched by these things but that was stupid.”

I ask him about the housing crisis, and it makes him think back to his time as a young man, leaving his childhood Kilbarrack home for the first time. “This is not nostalgia but I knew I’d have a room to rent by the end of the day, and I did. It was a class thing, the decision to do away with that layer of public housing.” He mentions Rosie, his film from six years ago, which centred on the housing crisis.

“I wasn’t naive to think a small-budget film would have a huge impact but the problem has just gotten worse and worse. It’s not because of immigrants; it’s because of doing away with public housing, shutting down the capacity of councils to build their own houses. This dreadful, ridiculous faith in the marketplace – that’s all it is.” Does he have faith in anybody in politics in Ireland today? “I wouldn’t write them all off. That’s too easy. I think there are a lot of people who are, in their own way, quite impressive. But I don’t have any great, deep conviction.”

Has he mellowed as he has become older? Does he still get angry? “No, smug ever since I heard that Public Image Limited song Rise. Those lyrics, ‘Anger is an energy’”. He remembers working on the Roy Keane book and asking him if he knew that song. “Roy sat up even a little bit more, he said ‘That’s my favourite song’ ... It makes sense, not just for him.” (When I ask him more about his friendship with Roy Keane he politely declines to offer any insights or anecdotes, which, in fairness, is probably the most sensible way to remain friends with Roy Keane.)

“I think there has to be an energy,” he says, continuing his reflection on the importance of anger in life and art. “And actually, when I’m writing, anger and joy are very close. I don’t think they are contradictory. But in a broader sense, am I angry? Not really. I like my life.”

The Woman Behind The Door by Roddy Doyle is out now.