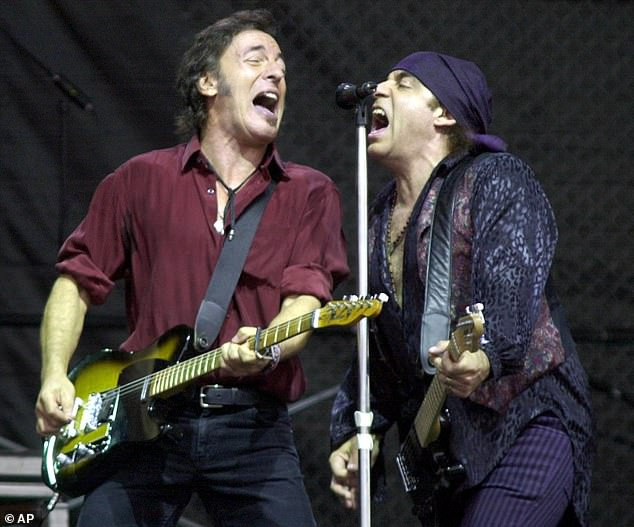

On stage at Wembley Stadium in late July, performing alongside his childhood buddy Bruce Springsteen, Steven Van Zandt looks entirely relaxed as the E Street Band hammer out Born to Run, Dancing in the Dark and The Rising to 90,000 fans. Twenty-four hours later, on stage at a screening theatre in Soho after the premiere of Disciple, an HBO documentary about his life, Van Zandt stands in front of just 100 people, many of them close friends and colleagues, and looks as if he’d rather be anywhere else.

“I don’t want to be the centre of attention,” he tells me the next day. “It’s embarrassing. I’m not shy but I don’t want to be the main man. I learnt to be a frontman with my own band but I never needed the spotlight — and superstars, they do need it.”

At the TV premiere, Van Zandt, resplendent in his trademark bandana and a purple velvet get-up, shuffles nervously as various high-powered producers and executives sing his praises, hymning his musicianship, longevity, star turn as Silvio Dante in The Sopranos, seminal anti-apartheid activism, respected radio show (Little Steven’s Underground Garage) and all-round top-notch-fella credentials. After a while he calls a halt. “Let’s eat,” he rumbles, sounding a lot like the consigliere who ran the famous Bada Bing! club in The Sopranos. The high point of the documentary is the footage, previously thought lost, of Van Zandt’s wedding to Maureen Santoro on New Year’s Eve, 1982. Springsteen was best man, Percy Sledge sang When a Man Loves a Woman and, best of all, the presiding minister was Little Richard.

I meet him in a suite at Claridge’s not long before he has to head for the soundcheck prior to that night’s second, triumphant Wembley gig. “Wembley’s always special,” Van Zandt, 73, says. “That’s where we did the [Free Nelson] Mandela shows, which were historically important. This whole tour, the audience has been more intense. We may be closer to the end than the beginning but we’re not going out quietly.”

I mention my surprise that several of my much younger colleagues went to see the band. “Yeah, some kid said to me, ‘We came because we heard you play live!’ I didn’t see that one coming! That’s become a thing. We take pride in having zero production — no light show, no gimmicks, no trying to turn a stadium into a club. We’re a throwback to the previous 50, 60, 70 years of rock. This young generation, they’re not prejudiced against different styles, or against anything, really. Gives you hope, don’t it?” Van Zandt says with a chuckle.

Beyond the E Street Band: A Multi-faceted Career

Keeping up a tradition of intense live music is doubly important to Van Zandt because he has a messianic sense of the liberating power of popular music and works to spread the word. Earlier in the week he had visited Beckmead College in south London to see his TeachRock initiative in action. TeachRock tries to engage disadvantaged youngsters across the school curriculum via their favourite artists. Beyoncé goes back to Aretha Franklin, Motown and the civil rights movement, for instance. He despairs of much conventional education as ill-suited to many pupils. “I want to turn Stem [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] into Steam by adding in the arts,” he says.Van Zandt is a connoisseur of popular music history. As Paul McCartney drily confesses in Disciple, “I know a lot but Stevie knows more.” The guitarist has dedicated much of the past quarter of a century, since he rejoined the E Street Band in 1999 after a 15-year hiatus, to disseminating that encyclopaedic knowledge. His weekly radio show is syndicated to 200 stations across America, playing obscure classics from 60 years ago alongside little-known contemporary bands. He has a record label and periodically puts together line-ups for charitable causes. He is also programme director for two stations, one of which, Outlaw Country, plays the darker, edgier material shunned by mainstream country radio.

“I happened to be in Nashville one day talking to this cat named Tony Brown, who was Elvis’s piano player and ended up starting record companies — a big deal. He said the last three people he produced — George Jones, the Mavericks, slightly off stuff — couldn’t get on country radio. They won’t play Johnny Cash any more! I thought, ‘It’s time for a new format.’” Heartland radio shunning the Man in Black for his leftism speaks to the polarisation of America. “Yeah, it does, like when the Dixie Chicks criticised George Bush. It’s sad.”

A Legacy of Activism: From Sun City to TeachRock

In the 20 years since he founded Outlaw Country, American politics has become greatly more divided, with senior Republicans talking openly of the possibility of civil war. “Those things used to sound like hyperbole,” Van Zandt says with a sigh. “Not any more.” Is Springsteen, supposedly the ultimate heartland rocker, unable to play in certain places now? “Well, our audience is much less mixed than it was, politically. When Bruce got vocal behind the Democrats, we probably lost half the audience. There’s nowhere we can’t do business but some places, yeah, they feel a bit like enemy territory. We’re ten times bigger in Europe. We might play six stadiums in America and sixty in Europe.”As the Wembley dates demonstrate, nowhere is the Boss and his band more enduringly revered than in England. The respect is mutual. “That British invasion period, 1964 to 67, was the ultimate for me,” Van Zandt says. “The Who, the early Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks, they set our standards very high. We had to be a dance band, pull people out of their chairs like those bands did. By the Seventies people were sitting down at rock shows. But we were a bar band — we had to be intense. We’re the last of that tradition. When we go, we will not be replaced, man, not really. Yeah, there’s Pearl Jam, Green Day, Chili Peppers, but they’ve been going 20 to 30 years. Who’s breaking through now?

“We were the luckiest generation ever,” he continues, “before it all got corporatised. You saw it in literature and cinema too. There’s never been anything quite like it. We may end up being a blip on the radar screen of history but it was a helluva blip, man, y’know? There’s something about the communication power of rock’n’roll that is like nothing else.” This zeal for his genre is why the documentary is called Disciple. Van Zandt, as Springsteen says on film, is “a true believer” in the redemptive power not only of rock but of soul, reggae, the blues, folk, anything authentic.

That ideal was realised most spectacularly in his Sun City initiative in the mid-1980s, when Van Zandt wrote the anthem urging artists to respect the boycott of the eponymous music venue in apartheid South Africa. He then co-ordinated an extraordinary line-up of stars — including Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Lou Reed and Miles Davis, for goodness’ sake — to sing it. In Disciple, Bono credits Van Zandt with inspiring his activism. “Stevie acknowledged rock’n’roll owed a debt to Africa,” he says.

“Well, yeah,” Van Zandt says. “Elvis’sfirst single [That’s All Right/Blue Moon of Kentucky] symbolises exactly what rock’n’roll was going to be. One side the blues, on the other the Appalachian, Scots-Irish hillbilly folk country thing. Black and white. One of the great joys of TeachRock is explaining to black kids they have absolute historic permission to play a guitar and be in a rock’n’roll band. They half invented it. Black kids are not gonna know that unless you tell ’em.”

The Inside Story: A Candid Look at a Life Less Ordinary

Going back to the documentary, self-effacing as he is, Van Zandt is still delighted with the result. “They asked me 20 years ago and I resisted it. Then I agreed but refused to be interviewed. Then Maureen, my wife, said, ‘Come on, you can do this without it being a narcissistic trip — just tell the truth.’ It came off OK. I’m so grateful. I’m not the most commercial subject. I’ve had some success, yeah, but I’m not a household word … and friends I’ve known for years, Jackson Browne, Bono, Paul McCartney, I didn’t know they thought that about my work! It was wonderful to hear that.”Like being at your own memorial service? “Exactly, I’m not supposed to be there! I’m supposed to be, like, dead.” Not yet, Stevie. Not by a long way.

A Career of Collaboration: From Springsteen to The Sopranos

Whenever you see Steven Van Zandt on stage with the E Street Band, he looks like he’s having the greatest time it is possible to have in showbusiness, dressed like a wild rock ’n’ roll gypsy, colourful bandana and scarves flying, a huge grin on his characterful face as he fires off licks on his electric guitar or spits harmonies into the same microphone as his lifelong friend Bruce Springsteen. When I ask if it is as much fun as it looks, he roars with delight. “Nobody’s that good an actor!” laughs the 73-year-old, flashing a mouthful of shiny American teeth.

The New Jersey native has, in fact, won acclaim and awards for his acting, most notably in The Sopranos. “I mean, I’m pretty good, but not that good!” Van Zandt chuckles. “I don’t know if I have the range to pretend to be somebody’s best friend for 60 years or more, you know?”

He speculates that the tangible camaraderie in the E Street Band had its origin in the British invasion of the 1960s. “You remember that scene in Help! where the Beatles walk up to a row of flats, and they all open a different door, and they go in, and then they’re all in the same room in the same house? When Bruce and I were starting out, we took that stuff literally, that everybody in a band was best friends. We bought the whole thing, we bought the illusion; only in our case, it’s real. We really have been best friends since we were 15 years old. I don’t think it’s something that can be faked. I mean, he still makes me laugh, man, you know? He’s a funny guy, even after all these years. We have a good time.” Tonight, the band play the second of two dates at Wembley Stadium.

Springsteen and the E Street Band have a justified reputation as the greatest live band in the history of rock, yet they play some of the most basic shows ever to appear in stadiums: just musicians, a couple of screens, and an audience roaring their lungs out. “We come from the bars and clubs. We were a dance band, and I think that’s a critical factor. The idea was to get people hot and bothered and wanting to drink more. And that requires a bit of extra energy, all right? To pull people out of their chairs and make them dance is different than playing a concert where everybody’s sitting down. At some point, we started taking great pride in the fact that we had no production. Literally none. It’s not something we particularly need. We just ignore the size of the venue and treat it like a club.”

Van Zandt has been Springsteen’s right-hand man for much of his career, as a collaborator, adviser, arranger, co-producer and general sounding board. “The underboss, the consigliere,” as he puts it, employing the mafia language of his most famous television role, as Silvio Dante, the closest confidant of the gang boss Tony Soprano. “I really don’t like being the centre of attention. I got quite good at it when I had to, fronting my own band in the Eighties, but I’d rather be the guy behind the guy, that’s my natural inclination. I don’t need to be in the spotlight.”

Nevertheless, he is now starring in his own documentary, Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple, a two-and-a-half-hour epic from the award-winning director Bill Teck, depicting one of the most extraordinary careers in rock history. “It’s funny, because first, Stevie didn’t want it to get made, then he didn’t want to be in it,” says Teck. “I’m like, ‘Stevie, are you sure you’re a rock star, man?’ Because most rock stars really like to be on camera.”

Six years in the making (and almost 20 years since Teck first approached Van Zandt), Disciple encompasses not just his storied history as a rocker and actor, but also as an outspoken political agitator on global causes, and a dedicated preserver of rock and soul music heritage, the driving force behind numerous specialist record labels, syndicated radio shows and high-school education programmes. “I said to Bill, ‘Maybe you can explain my life to me,’” chuckles Van Zandt. “I don’t really get it from the inside out.”

The cast list is a testament to his influence and features rock superstars, including Springsteen, Paul McCartney, Bono, Jackson Browne, Peter Gabriel and Eddie Vedder, alongside an enthusiastic retinue of hip-hop stars, soul singers, original rock ’n’ rollers, punks, politicians, filmmakers, journalists and actors. There’s archive footage of Miles Davis at sessions for the 1985 anti-apartheid single Sun City, and Little Richard officiating at Van Zandt’s 1982 wedding to Maureen Santoro, with Springsteen as best man, and Percy Sledge leading the band from The Godfather in a version of When a Man Loves a Woman. “I had no real idea that people felt that strongly about what I was doing,” admits Van Zandt. “Even Bruce is saying things that he has never said to my face before. Honestly, that was mind-blowing for me.”

McCartney describes Van Zandt’s knowledge of music as “encyclopaedic – I know quite a bit, but he knows more”. There is thrilling footage of the veteran Beatle performing I Saw Her Standing There with Van Zandt’s fantastic band, the Disciples of Soul. “You have to compartmentalise, to put your 13-year-old self away and switch your mind to thinking it’s just a friend coming on stage to jam,” he says of performing with McCartney. “You cannot think about putting the needle on the first album you ever bought. You treat him like an equal, a peer, another cat that loves the music.”

The most moving section of the film digs into Van Zandt’s 1980s career, when he left the E Street Band in 1984 at the height of their Born in the USA success (an album he co-produced) to create some of the most fiercely political rock music ever heard, engaging with issues ranging from Native American rights to the destruction of the rainforest. “As an impressionable teenager, I was fanatical about Stevie, I thought he was the most important rock star in the world,” admits Teck. “There would be reading lists on the back of his albums, which informed a lot of my thinking, encouraged me to consider things in the kind of critical way he did, and not just accept received versions of events.” Van Zandt’s 1985 all-star album Artists United Against Apartheid became a vital focal point for calling for sanctions against South Africa (for which Van Zandt lobbied energetically in the US senate). When Nelson Mandela came to New York for the first time in 1990, he thanked Van Zandt personally. “It was the most thrilling moment of my life,” he admits.

There was a fallow period in the 1990s. “I was spiritually and emotionally exhausted,” he confesses. He remains involved in actively preserving rock-music heritage, particularly through educational initiatives, but has drawn back from front-line politics. “Everybody’s welcome at our shows, man. I think our politics are pretty obvious, but they are not party driven: we believe in the basics of equality and democracy and freedom, the things that we would think everyone would care about. We care about people, OK.”

Van Zandt made a comeback at the end of the decade, as an actor in The Sopranos and as his oldest friend’s foil in a reunited and revitalised E Street Band. Yet there has been a narrative vein of looming mortality running through recent Springsteen albums and shows, which has led fans to speculate that this might be their final reckoning.

“You never know,” admits Van Zandt. “I mean, we treat every show like it could be the last show, and we’ve been doing that for 50 years. But the audience is still there, and we can see them getting younger every year. I don’t see the end anywhere in sight, to be honest, especially in Europe, where we’re bigger than we’ve ever been. I think we can play every summer for evermore, man. I love that the Stones are still out there. Because as long as they’re out there, man, we’re still the new kids on the block, right? So I’m good with that.”

A Lasting Legacy: The Importance of Rock 'n' Roll

Rock’n’roll needs its sidemen, collaborators and co-writers. It needs its archivists and advocates, its arrangers and backing singers. There are endless positions other than megastar, and Steven Van Zandt has fulfilled most of them. Disciple, a sprawling biography of one of rock’s most likable veterans, is a document of several lives, all well lived by the same man.

Van Zandt was part of the New Jersey music scene of the early 1970s, which had its own signature sound: classic rock’n’roll beefed up with the punchy horns of Atlantic and Stax. Bruce Springsteen already had a record deal, but he kept coming back to play in Asbury Park’s sweat-soaked clubs. One day, when he felt one of the songs on his next album might need a bit of home-town grit, he called his old pal Steve. Van Zandt breezed into the studio, agreed that the track sucked, and 20 minutes later Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out had been revitalised, smothered in that loose Jersey brass. It was one of the highlights of Born to Run, Springsteen’s 1975 breakthrough. After then, Van Zandt became a key member of Bruce’s backing group, the E Street Band.

Our man was at this point known as Miami Steve, on account of the time he returned from a stint playing gigs in Miami, sporting colourful clothing that he then kept wearing in the far less sunny New Jersey. Interviewed here, he recalls his thought process: “Fuck winter, I’m done. I’m tropical from now on!” It’s one of countless irrepressible anecdotes doled out by the Van Zandt of today, filmed leaning on the back of a turned-around chair like a cool supply teacher. The tie-dye top he’s wearing is, by his standards, restrained: one of the glories of his career and of this film is his unique styling. Assembled underneath the trademark wide bandana that has kept the top of Van Zandt’s head from public view for five decades, the Miami Steve look evolved into an aesthetic that was roughly “Purple Rain-era Prince losing a fight with a fairground clairvoyant”: variously we see leather waistcoats, white tank tops, and a trenchcoat apparently made of five different carpets; fingerless gloves, voluminous blouses, tasselled earrings and so, so many silk scarves.

Immunity to ridicule is a quality shared by all the best pop stars, and in the 1980s Van Zandt fearlessly invited mockery in a new way. Just as Springsteen was hitting paydirt with Born in the USA, Van Zandt split from him and rebranded under the banner Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul, singing political songs. Disciple is perhaps too kind to Van Zandt’s activist era, giving the impression that the campaigns were more impactful and the records more listenable than they were. Now and again, however, Little Steven made a big impression.

By far Van Zandt’s biggest success on the political stage was Artists United Against Apartheid, a Band Aid-style supergroup whose 1985 song Sun City promoted a creative boycott of apartheid South Africa. Van Zandt assembled an unbelievable roster for the recording: the footage of Melle Mel, Ringo Starr, Pat Benatar, Bono, Keith Richards, Lou Reed, Bobby Womack, Jimmy Cliff, George Clinton and scores more is impressive enough, even before Miles Davis wanders in to lay down a bit of trumpet. The clip of Van Zandt at one of the spin-off live gigs, swathed in textiles of every conceivable colour, addressing a stadium full of fans with the words, “We the people will no longer tolerate the terrorism of the government of South Africa. We will no longer do business with those who do business with the terrorist government of South Africa.” It’s an air-punch moment and an illustration of the sort of money-meets-mouth moral fortitude that music could use more of today. But the truth was that Van Zandt was generally more effective as a facilitator of other people’s genius. With his music too eclectic to maintain a fanbase and his lyrics too strident for him to be loved by record companies, his solo career stalled.

Van Zandt took time off (“I went out into the wilderness, man; I walked my dog for seven years”) before rejoining Springsteen and the E Street Band, returning to the role of the dependable sidekick. That might have been that, but then Sopranos creator David Chase had a flash of inspiration, hiring one of rock’s great consiglieri to play the mafia version of the same. Silvio Dante was just like Steve, on the edge of the spotlight but always giving the end product extra sparkle and guts.

The Sopranos was a surprise third act for Van Zandt, yet it had been well earned by a man whose expertise and passion has put smiles on faces for nearly half a century. Disciple, meandering and exhausting – but with more entertaining moments than dull ones – is an appropriate tribute.