A dispute over whether Francis Ford Coppola exhibited unprofessional behavior on the Megalopolis set is intensifying, with multiple parties filing criss-crossing lawsuits.

On Wednesday, Coppola sued Variety for defamation. He denied claims that there weren’t any of the traditional checks and balances in place to protect against sexual harassment and accused the publication of falsifying the statements. This followed one of the extras on Monday filing a lawsuit detailing claims of sexual harassment against the director.

The lawsuits were filed with Megalopolis set to be released in roughly two weeks.

In a statement, Variety, whose parent company also owns The Hollywood Reporter, said, “While we will not comment on active litigation, we stand by our reporters.”

Variety reported in July that Coppola “appeared to act with impunity on set” following a prior story from The Guardian that claimed he “tried to kiss some of the topless and scantily clad female extras.” It reported, citing two sources, that his behavior was “unprofessional” and that the director “kept leaping up to hug and kiss several women, often inadvertently inserting himself into the shot and ruining it.” Coppola subsequently demanded a correction and retraction from Variety, which declined to do so, according to the complaint.

In the lawsuit, Coppola said that a video attached to the article purportedly showing him trying to kiss some of the extras did not actually do so. He also denied claims that the production didn’t have a human resources department to deal with claims of sexual harassment.

Additionally, the director challenged allegations that he ruined scenes by inserting himself into certain shots.

“The true facts are that there were four cameras shooting during the above-referenced scene and three of the cameras were mobile, with the crew often changing positions,” the complaint states. “Therefore, due to the multiple camera angles, at different times, members of the crew and Coppola were in some of the shots. That was anticipated and unavoidable. That is one reason why shots are edited.”

For the production, cast and crewmembers signed a nondisclosure agreement, which the complaint states was meant to “assure discretion and confidentiality” and “avoid outside interference or involvement.” Coppola, who seeks at least $15 million, argued that Variety should’ve known its sources were “unreliable” because they signed a nondisclosure agreement, which they breached.

Coppola in a statement called Variety’s reporting “false, reckless and irresponsible.” He added, “No publication, especially a legacy industry outlet, should be enabled to use surreptitious video and unnamed sources in pursuit of their own financial gain.”

The director’s denial of reports of unprofessional behavior runs up against a lawsuit filed by Lauren Pagone, an extra during the disputed nightclub scenes, in Georgia state court.

In her complaint, Pagone alleged that Coppola kissed and touched her without consent despite being told that there would be no sexual content in the shots. She said an intimacy coordinator wasn’t provided for the scene with whom she could discuss her concerns. The lawsuit brought claims for battery, assault and negligent failure to prevent sexual harassment, among others.

In June, Lionsgate revealed that it’d bring Coppola’s $120 million passion project to U.S. theaters. It didn’t pay for marketing, with the director footing the bill.

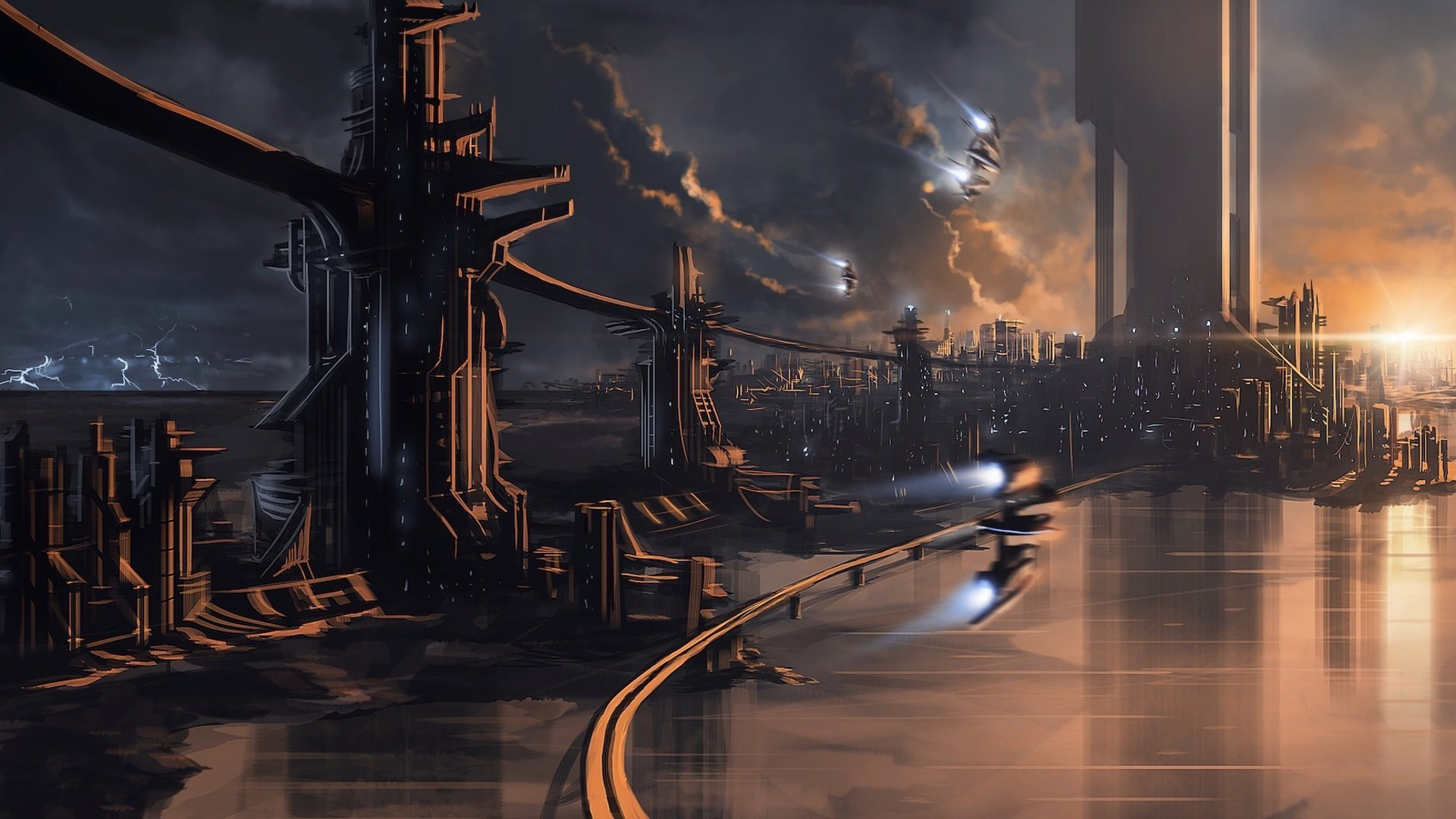

Coppola’s Vision: From Ancient Rome to Modern America

Inspiration first struck when Coppola was mulling Roman epics in the late 1970s, between the releases of The Godfather Part II and Apocalypse Now. He found himself drawn to a political conspiracy of 63 BC, in which the senator Catiline hatched a bloody and ultimately thwarted plot to whip up the empire’s poor and disenfranchised and overthrow the Senate. Then came the twist – not unlike the one that led Coppola and his co-writer John Milius in the late 1960s to relocate Joseph Conrad’s 19th-century novel of colonial Africa, Heart of Darkness, to contemporary war-torn Vietnam. “I suddenly realised: what’s ancient Rome today?” he says. “It’s America.”

As time passed, the notion of the United States as a capsizing empire only became more resonant. (Coppola points out that his gift as a filmmaker has always been foresight: only months after filming wrapped on his wire-tapping thriller The Conversation, the Watergate scandal broke in the American press.) But in the intervening years, the project continually stalled – and after the release of his 1997 courtroom thriller The Rainmaker, an increasingly jaded Coppola took a self-imposed “extended sabbatical”, to reflect on his method and style, and purge his frustrations with Hollywood.

The Hollywood Rebellion: A Tale of a Maverick

The system had happily grown fat on his hits: the first two Godfather films helped save Paramount; the box office for Bram Stoker’s Dracula rivalled Batman Returns. But it had also long resented his breezy rejection of its customs and methods, right from his early defiance of the union rules, which in the 1960s had the studios in a straitjacket.

Today, the same goes. No studio would fund Megalopolis, so Coppola drummed up its $120 million budget himself by selling off much of his thriving Californian wine empire (while retaining the Inglenook estate in the Napa Valley, which he bought in 1975 with the proceeds from The Godfather).

Ergo, the resentment still simmers. Shortly before Megalopolis’s premiere at Cannes, articles appeared in Variety and the Guardian featuring anonymous grumblings about chaos on set – and potentially more damaging claims, also anonymous, that Coppola had made inappropriate physical contact with a number of female extras during the filming of a nightclub scene.

In supposed bombshell video evidence, he could be seen talking to two actresses, cordially embracing a third, and briefly dancing with a fourth – who later posted on social media that Coppola had done “nothing to make me or for that matter anyone on set feel uncomfortable,” and clarified the waltz was at her instigation. “He was nothing but professional, a gentleman, he was like this cute Italian grandfather, running around the set,” she added.

Yet Variety then found that third actress, who told the magazine she had been “in shock” at Coppola’s conduct, and is now suing him and others for damages. Two days after our interview, it got messier still. Coppola himself (who had already denied he had shown any “disrespect” to the women) is now suing Variety for libel, over alleged “false and defamatory statements” in the article, the accompanying video, and the “malice” the outlet allegedly showed towards him. Strong word – but to an onlooker, the tone of their coverage was odd: between the lines you sensed a flinty determination to make something, anything, stick.

“You know, I always felt like a creation of Hollywood,” Coppola ventures. “I went there in pursuit of all these beautiful things they were making. I was in awe of the place. I got to work for Roger Corman; I got to meet Vincent Price. Now, Hollywood doesn’t want me any more. They’re the parents that disown the unruly child – they created me, now they don’t want me. I understand it, but it still hurts my feelings. I accept it, but I also can’t.”

As for the reported chaos during Megalopolis’s production: “In Hollywood, the word chaotic only means ‘not what we’re used to’,” he snorts. “What the studios do today is make Coca-Cola. They know there’s a good chance they’ll make money, providing the flavour stays the same. But art is chaotic. When it’s efficient, something’s going wrong.”

A Legacy of Innovation: From Megalopolis to Glimpses of the Moon

Assembling the film’s cast would probably have been trickier under a studio’s eye. It includes two notably “cancelled” talents, both of whom play veiled Trumpian analogues. There’s New Rome’s golden-coiffed banking mogul Crassus – played by Jon Voight, one of Hollywood’s rare out-and-proud Trump supporters. “Art is above politics – or, at least, it should be,” Coppola shrugs. “My cast are all going to be voting in different directions in the coming election, and I love every last one of them.”

The second, playing sybarite-turned-demagogue Clodio, is the famously volatile Shia LaBeouf, who was either fired from or, as he strongly maintains, quit the recent thriller Don’t Worry Darling over what its director Olivia Wilde described as his “combative energy” on set. (LaBeouf is also due in court next month over domestic abuse claims made by two ex-girlfriends, including the singer FKA Twigs: LaBeouf denies the allegations.)

“Shia has had problems,” Coppola concedes. “He’s so talented, but he’s had a string of problems. And on set, he does create tremendous conflict. His method was so infuriating and illogical, it had me pulling my hair out. But I think he’s getting the set so charged with electricity that his reactions will have the ring of pure truth. Dennis Hopper did something similar on Apocalypse Now. He would be so nutty that even Brando wanted to throw bananas at him.”

Does he ever feel too old to still be weathering this stuff? He exhales. “Let’s say there’s an actor who can only do beautiful work if you hit him on the head with a monkey wrench. Do you do it?” I must look uncertain. “Of course you do it!” he roars. “The process is painful, but the outcome makes it worth it.”

Speaking of worthwhile outcomes, what of his latest film’s effect on his legacy? Megalopolis is transfixingly wild and ambitious – but also deeply divisive, as its festival outings have shown. “Legacy is weather,” he shrugs. “One minute you’re important, the next you’re forgotten, then you’re resurrected half a century after that. The prize I’m after isn’t awards or money. It’s when younger filmmakers who made something beautiful say ‘I wanted to make my film because I saw one of yours.’ My God, what a thing to be a part of that continuum.”

He warms to his theme. “Look at Jacques Tati. A brilliant French filmmaker, total genius, who took everything he had and borrowed money on top, so he could make the film no one wanted him to make. And it was a big flop. He lost everything. But that film was Playtime.” (Almost 60 years on, Tati’s comedy regularly features on critics’ lists of the greatest films ever made.) “I mean,” Coppola laughs, “there’s no better movie. When you jump into the unknown, you prove you are free.”

Another such bound lies directly ahead. Though Megalopolis has the air of a closing artistic statement, Coppola already has his next film ready to shoot. Titled Glimpses of the Moon, it’s a loose adaptation of a 1922 Edith Wharton novel, “with strong dance and musical elements”, he explains. “I’ve turned it into a very odd confection.”

He hopes to shoot it in the UK and Europe – “funded the conventional way, with the help of national subsidies, because I’m all borrowed out” – after a planned move to Putney, in southwest London. In April, Coppola lost his wife of 61 years, the documentarian Eleanor Coppola. “And now whenever I’m in Napa, I miss her every day. So I want to live in London now, because it’s the one place I don’t have any memories of ever being with her.”

The thing he’s looking forward to most is figuring out how to make this new film as he goes along: the old buccaneer casting off one more time. “The future of cinema is something we can only dream and wonder about,” he says. “And we can’t have the slightest inkling as to what it will be.

“But I will tell you this,” he adds, a finger raised. “The movies your great-grandchildren are going to make will be extraordinary.”

Megalopolis is out on Sept 27