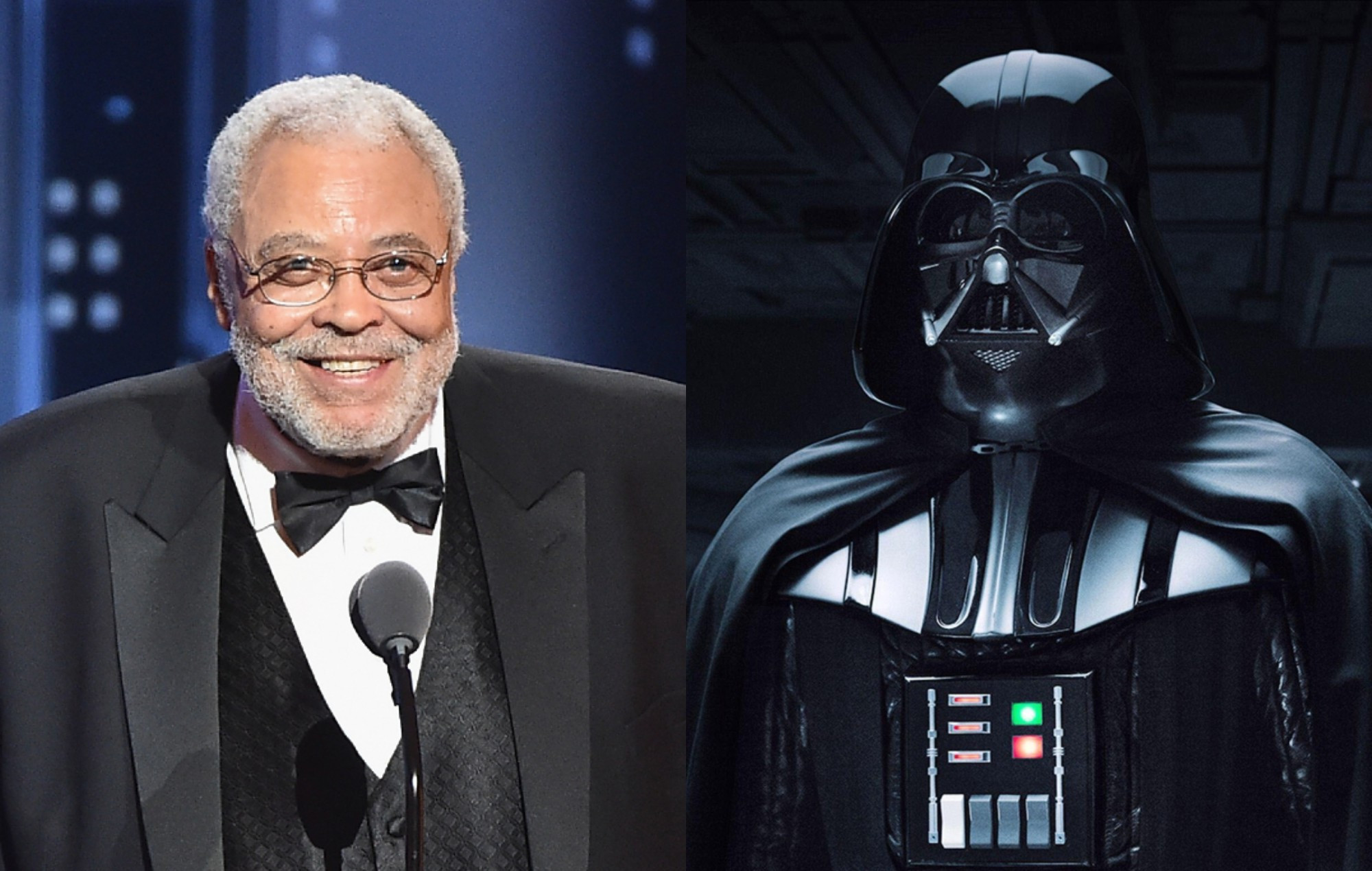

When people talk about the late, great James Earl Jones, it’s a guarantee that one of the first things they’ll mention about him is that voice. It’s an inevitability, really, when anybody who was born after 1977 was likely first introduced to him not as a physical presence but as a sound booming from their screen — either filtered, steely, and imposing as the snarling vocals of Darth Vader in the original “Star Wars” trilogy, or warm, stately, and regal as the dialogue from Mufasa in Disney’s animated classic “The Lion King.”

But even in his live-action roles, Jones possessed a voice that could stop you in your tracks. Born in 1931 Mississippi and raised in Michigan, Jones had a childhood stutter so difficult that he claimed to barely speak before his first year of high school, where reciting poetry helped him to overcome the impediment. And when he did, he unlocked a powerful Basso profondo voice — deep and rich, gravelly and filled with conviction and authority — that lent an immediate air of gravity and sophistication to anything he said. Sometimes this could be amusingly subverted, like his late career kick as a breakdancing Verizon spokesperson, or when he voiced Maggie Simpson in an episode of “The Simpsons.” Most of the time, it was a tool in his arsenal that he could use to bring a scene to breathtaking life, adding menace or compassion to a character and a theatrical thrill to any project.

Of course, Jones wasn’t just his voice. The actor had a power and intensity as an actor that revealed his years of stage experience before breaking through on the silver screen. While he’s best known today for his contributions to popular cinema — be it franchise work like “Star Wars,” comedies like “Coming to America,” or family classics like “The Sandlot” — Jones arguably did his best, most vital work in theater, making his Broadway debut 1957 and starring in Shakespeare plays (among them “Othello,” “Hamlet,” and “King Lear”), modern dramas, and comedies alike. He picked up two Tony Awards across his lifetime: one for 1968 boxing drama “The Great White Hope,” which he would reprise his role for in a film version that saw him receive an Oscar nomination, and as the originator of the part of Troy in August Wilson’s searing, legendary 1985 chamber drama “Fences.” Two Emmy Awards for miniseries “Heat Wave” and procedural “Gabriel’s Fire,” a Grammy for (of course!) a spoken word album, and a 2011 honorary Oscar made him one of the few EGOTs before his death.

All of Jones’ experience on stage showed. He wasn’t a performer who sank into a role as much as he elevated it, bringing commanding presence and deeply felt history to the men (and lions) that he played. Although his later years saw him play many an authority figure — mentors and side characters — in the ’70s and ’80s, he could take on parts that ranged from tormented boxers to carefree garbage men, and make them feel both grandly larger-than-life and still deeply human. Whether starring in a sci-fi epic or a small New York romantic drama, Jones brought something to his films no other actor was capable of.

In celebration of Jones’ life after his passing on September 9, IndieWire is revisiting the greatest, most remarkable screen performances from the icon. Entries are unranked, and instead listed in chronological order by film release date. Read on for 12 of James Earl Jones’ greatest performances.

James Earl Jones’ Greatest Film Roles

The Comedians

“The Comedians” is not a great movie, or even a particularly good one. But it’s an interesting one. And a rewatchable one. And part of that is due to James Earl Jones in his first major film role, following a bit part in ‘Dr. Strangelove.’ In Peter Glenville’s film, based on Graham Greene’s novel of the same name, Jones was just 36, but had already had a legendary stage career and was capable of bringing tremendous gravitas to this role of a cultured surgeon who also happens to be a rebel leader fighting against the regime of ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier in Haiti. Already, he is someone you feel you could risk everything for to follow into battle and, probably, doom. There’s a particularly great moment where Jones’ Dr. Magiot is trying to enlist an English arms dealer to his cause. That arms dealer is played by none other than Alec Guinness. Ten years before Darth Vader confronted Obi-Wan Kenobi aboard the Death Star, here are Jones and Guinness playing roles that are a bit like their ‘Star Wars’ characters, only reversed: Here Jones is the rebel leader and he’s trying to enlist a servant of empire to his cause. Alas, Guinness’s character does not have the convictions or the courage to be a truly worthy ally. —CB

The Great White Hope

A consummate craftsman, Jones was a man of both the screen and stage. He brought his performance in Howard Sackler’s ‘The Great White Hope,’ which won him his first Tony in 1969, to film audiences a year later with his co-star Jane Alexander also reprising her role. Together, they were nominated for Best Actor and Best Actress Oscars, using a script adapted by the playwright and directed by Martin Ritt.

This period sports drama loosely based on a true story was maybe more impressive when blocked as a live Broadway performance (at least going by clips and descriptions), but Jones manages a tour de force performance all the same as the fictional Jack Jefferson — as inspired by the real scandal-ridden pro-boxer Jack Johnson. The actor exudes hubris in this tragic interracial love story, centering the first Black heavyweight boxing champion and his tortured interracial marriage to Eleanor Bachman (Alexander).

The real Johnson made headlines when he coupled up with Brooklyn socialite Etta Terry Duryea (Alexander). At 31, Duryea died by suicide, and Johnson, who faced excessive racist scrutiny from the mostly white men managing his sport already, gained further notoriety. Johnson’s rise and fall is explored as an allegory here and Jones demonstrates himself as an exquisite shepherd for its nuances as Jefferson. The final shot of the film, which sees the bloody character carried away from the ring, showcases Jones’ steeliness as an indelible image of defiance with just the right touch of his signature humor. —AF

Claudine

Opposite an intoxicating Diahann Carroll as the titular ‘Claudine,’ the undeniable Jones charms and devastates as Roop Marshall — a dashing leading man in an at-times painfully earthbound Harlem romance that’s in its own way poignantly delightful by the end. The charismatic garbage collector falls for the single mother of six fast, but is quickly reminded that Happily Ever After isn’t so easily won for a Harlem woman living on welfare.

Director John Berry’s soulful dramedy from 1974, which was co-written by husband-wife duo Lester and Tina Pine (you’ll feel that wise familiarity in the script), allows Jones one of his most endearing and understanding portraits. The picture of a man doing his best in any decade — as seen here with some especially funky hats and shirts — Roop proves an ideal framework for getting to know the sparkly-messy domesticity that is Claudine’s world. He’s also the perfect conduit for considering the ties that bind intimacy and imperfection within any family, but especially those stuck in a cycle of poverty.

Roop spends much of the film attempting to sell himself to Claudine’s kids. The sobering reality that a marriage between the two could undercut the family’s welfare makes that pitch tougher and Jones brilliantly navigates the patience that situation demands. His demeanor gives way when the script demands it to reveal a vulnerability that’s even more memorable than the toothy smile he shows up with. Other Jones performances may bottle his bravado better, but ‘Claudine’ is your best bet for falling truly in love with the actor. —AF

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

For a $7,000 salary and just two-and-a-half hours of work in a recording booth, James Earl Jones helped create the greatest villain in movie history. Ralph McQuarrie had designed Darth Vader’s suit and helmet, sculptor Brian Muir made it a reality, David Prowse gave him imposing physicality, and John Williams gave him appropriately menacing musical accompaniment. But as collaborative a creation as Darth Vader was, this character would be nothing without James Earl Jones’ extraordinary voice. Can you imagine anyone else saying ‘I find your lack of faith disturbing?’ Or ‘Don’t be too proud of this technological terror you’ve constructed. The ability to destroy a planet is insignificant next to the power of the Force?’ You can hear the sneer in his voice when he says ‘And now Your Highness, we will discuss the location of your hidden rebel base.’ Or the notes of searching and befuddlement when sense an old friend and says ‘I sense something… a feeling I haven’t sensed since…’ Jones not only imbued this character with supreme resolve and even supernatural power, he came across as the ultimate unstoppable force. As much as Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan Kenobi himself, he made you believe not just in this galaxy far, far away but that there’s a Force that’s meaningful and all-encompassing and can be used for good or evil that binds us all together. He made you believe.

The remarkable thing is that he didn’t even expect much credit for the part. He told Newsday in 2008, ‘When Linda Blair did the girl in ‘The Exorcist,’ they hired Mercedes McCambridge to do the voice of the devil coming out of her. And there was controversy as to whether Mercedes should get credit. I was one who thought no, she was just special effects. So when it came to Darth Vader, I said, no, I’m just special effects. But it became so identified that by the third one, I thought, OK I’ll let them put my name on it.’ Even if he hadn’t claimed that credit, everyone forever would have known that Vader’s voice was that of James Earl Jones. Upon Jones’ death, Mark Hamill tweeted ‘RIP Dad.’ That’s how real Jones had made this singular cinematic creation.—CB

Roots

The ‘Roots’ saga stretches all the way from the mid-1700s with the book’s author Alex Haley’s ancestor Kunta Kinte (originally played by LeVar Burton) to the then present-day of the 1970s, with James Earl Jones playing Haley himself. Jones had an uncanny ability to portray being a seeker, an intellectual who could look further and deeper than anyone else. Someone who could see truths and dispel falsehoods that few others could. There’s a clarity he brings to the role of Haley, that of a torchbearer who illuminates both history and the ongoing bigotries of the present. Take a look at his incredible showdown with Marlon Brando’s George Lincoln Rockwell, the leader of the American Nazi Party. ‘You deceived me,’ Rockwell says. ‘No, sir I did not,’ Jones’ Haley immediately replies. ‘You asked me if I were Jewish. I told you the truth. I am not Jewish.’ And Haley from there has an ability to dispel everything that Rockwell says. Even Rockwell’s repeated use of the n-word. His Haley says he’s been called that word many times, but ‘this is the first time I’m being paid for it.’ Despite being a rock of fortitude and moral purpose in this scene, Jones finds subtle ways to show that he is nervous: His sweatiness, his scribbled notes, and the way he looks down at his notepad, all while Brando is hurls insults and blows smoke rings. That’s the thing: Jones could be a force but he’s also powerfully human, and he finds the interior life of even those he’s giving an implacable façade. —CB

Conan the Barbarian

James Earl Jones had an incredible knack for making outlandish villains seem downright believable. In ‘Conan the Barbarian,’ he plays Thulsa Doom, the leader of a snake-worshiping death cult whose deeds are almost as bad as the wig Jones was forced to don. But while ‘Conan’ might have seemed like an inherently campy project on paper — after all it was a pulp fiction adaptation built around a professional bodybuilder who was cast in the role for his comically large physique — director John Millius was determined to tell a violent, operatic story of sacrifice and redemption. Jones embraced the task with gusto, lending his foreboding presence to an evil role that became the perfect foil for Schwarzenegger. The role itself was a combination of several other characters from Robert E. Howard’s ‘Conan’ books, but the onscreen alchemy that fused their elements together was the result of Jones’ genius. —CZ

Matewan

The labor movement in America is having a moment right now. Between last year’s strikes related to the entertainment and auto industries, as well as continued collective bargaining for better conditions at Amazon, the word ‘union’ seems to be top of mind for many working-class folk. As such, John Sayles’ deeply reflective ode to the risk and violence West Virginia miners faced in working to unionize during the 1920s may be the perfect film to capture the current ethos of our country. In the film, Jones plays ‘Few Clothes’ Johnson, a Black mine worker faced with scabbing against his white peers on strike, but who chooses not to, thereby pushing other laborers of color to do the same. The intensity Jones brings to his performance is enough to inspire anyone to put down their pick and shovel (or whatever tool your job requires) and stand up for the rights of their fellow workers. While there are plenty in ‘Matewan’ who refuse to see past his race and the indignity they believe should be put upon him, Jones and his character remind viewers that, to the major corporations trying to stiff their staff, everyone is exactly the same. —HR

Coming to America

Much of the humor in ‘Coming to America’ stems from Eddie Murphy’s fish-out-of-water performance as Akeem Joffer, an African prince who travels to New York in search of a bride. But that juxtaposition is only possible because of how well the film fleshes out his fictional home country of Zamuda before it sends him out into the real world. As Akeem’s father, King Jaffe, James Earl Jones perfectly embodies both the ridiculous opulence and the strict traditionalism that served as foundational pillars of Akeem’s upbringing. The role is not entirely unlike his regal voice performance in ‘The Lion King,’ but played to considerably more comedic results. It’s a perfect example of an esteemed actor leveraging their dramatic strong suits for laughs, proving to the world that the thespian was more than capable of comedy. He reprised the role for the 2021 sequel ‘Coming 2 America,’ which ended up being the final performance of his legendary career. —CZ

Field of Dreams

If Burt Lancaster’s country doctor is the heart of ‘Field of Dreams,’ James Earl Jones’ Terence Mann is its head, representing the perfect balance of emotion and intellect that combines to make baseball such a singular sport. A gruff writer living in Boston, Jones’ Mann has shut himself off from life, a bit J.D. Salinger-style. ‘Who the hell are you?’ he asks Kevin Costner’s dreamer Ray Kinsella when the Iowa farmer, pursuing those whispered cornfield voices saying ‘If you build it, he will come,’ shows up on his doorstep. ‘You got a learning disability here? Look, I can’t tell you the secret of life. And I don’t have any answers for you. I don’t give interviews, and I’m no longer a public figure. I just want to be left alone. So back off!’ Of course, he relents. Mann had wanted to be a baseball player himself at one time, and suddenly hearing the same voices Costner hears, he journeys with him back to Iowa. Baseball is ultimately a sport about connection, about players working in harmony toward a common end, where the next one up at bat is capable of achieving as much glory as those in front of him and those behind him. Jones captures that in one of the great inspirational monologues in all of the movies: ‘The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game, it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds of all that once was good and could be again.’ —CB

The Hunt for Red October, Patriot Games, Clear and Present Danger

While Jack Ryan is perhaps best viewed as an intellectual lone wolf who sees the enemy coming before anyone else, this CIA analyst-turned-field specialist would be nothing without the guidance of his boss, Deputy Director of the CIA and Vice Admiral James Greer, who Jones plays with a convincing touch throughout all three films he appears in. Opposite Alec Baldwin as Ryan in ‘The Hunt for Red October,’ Jones is a supportive mentor who knows his protégé is miles ahead of everyone else in the room, but well-acquainted enough with matters of diplomacy to know when to set him loose. When Harrison Ford took over the role of Ryan in “Patriot Games” and “Clear and Present Danger,” Jones remained, providing a throughline with the earlier film while at the same time adjusting the dynamic as they’ve both come into their own and are less mentor/mentee than co-workers. The last film expands their relationship even further by exploring how Ryan deals with losing his most trusted advisor and superior. Giving off the perfect amount of gravitas and mischief, Jones never feels like a background character, but is instead integral in giving Ryan the confidence to face down the world’s terror rather than shy away from a threat or fear of professional reprisal. —HR

The Sandlot

It’s rare that a kids film focusing on a sport that isn’t widely played outside of America breaks out in such a large way, but for many millennials, ‘The Sandlot’ shaped our understanding of what it means to be part of a team. Set in the late spring and summer of 1962, the film follows a new kid in town as he becomes integrated into a young, male friend group who spend most of their time playing baseball in a neighborhood lot behind a junkyard. Every so often a ball will land in the junkyard, guarded over by a massive dog they call ‘the Beast,’ but when the new kid manages to lose his father’s signed Babe Ruth ball over the fence, they’re forced to figure out a way to get it back. Turns out this feat is a lot easier than expected as the owner of the junkyard, Mr. Mertle, happens to be a former baseball player and continued lover of the sport. Played by Jones, Mr. Mertle proves to be a sage figure in the film, representing the importance the sport can hold for people of all ages and the legacy that can be built by forming a team with others. As for his own legacy, the film reminds us how Jones can perfectly balance fear and geniality at the drop of a hat, inspiring another generation to climb beyond the fences that keep us separated. —HR

The Lion King

A voice as distinct as James Earl Jones’ can be both a blessing and a curse, as its instant recognizability almost seemed to limit the types of roles he could convincingly sink into. But whenever a role came around that called for a deep bass range that commanded instant respect, Jones made creating cinematic magic look easy. Few actors have ever been better suited for a voice role than Jones was for Mufasa, a regal king who taught Simba the ways of leadership as he presided over the Pride Lands. Jones’ booming voice brought legitimacy to the film’s Shakespearean power struggles, but he was equally effective at playing the stern dad who had to remind his rebellious son that he did, in fact, have to wait to be king. The performance is so iconic that it was hardly surprising when Jon Favreau enlisted Jones to return for his ‘live action’ 2019 reimagining of the film. He was the only original cast member to return for the star-studded remake, illustrating just how irreplaceable the actor was to the franchise. —CZ